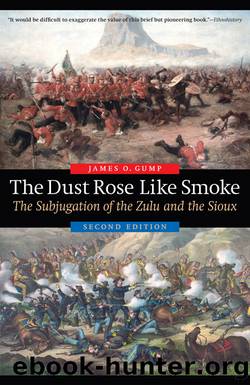

The Dust Rose Like Smoke by James O. Gump

Author:James O. Gump [Gump, James O.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: HIS001040 History / Africa / South / General, HIS036040 History / United States / 19th Century

ISBN: 9780803284531

Publisher: Nebraska

Published: 2015-10-21T00:00:00+00:00

5. Bartle Frere. Engraved from a drawing by Sir George Reid. In Sonia Clarke, ed., Zululand at War, 1879 (Johannesburg: Brenthurst Press, 1984), 54. Courtesy Brenthurst Press.

To support their case for war, Frere and Shepstone also made extensive use of missionary reports from Zululand, especially those of the Anglican Robert Robertson. Robertson, who enjoyed little success in attracting African converts, had grown frustrated and embittered by the late 1870s. A notorious drunk and vulnerable to the sexual attractions of young women on his station, Robertson blamed his personal misery on Cetshwayo and those âthousands of wild Zulusâ who had only âlearned the name of the Evil oneâ from the white man. By late 1877 Robertson lamented that as tragic as a conflict with the Zulu might be, âthere are worse things than war sometimes.â77

Frere had reached similar conclusions. Working feverishly during 1878 to lay the groundwork for confederation, Frere prepared the Colonial Office for war against the Zulu kingdom. In September, for example, he wrote that âthe preservation of peace in Natal depends simply on the sufferance of the Zulu Chief, that while he professes a desire for peace every act is indicative of an intention to bring about war, and that this intention is shared . . . by the majority of his people.â78 In manufacturing a casus belli, Frere exaggerated the significance of various incidents, including the exodus of missionaries from Zululand in mid-1878. Frere informed the colonial secretary that virtually every missionary had been âterrified out of the country.â Although Cetshwayo disliked most Christian missionaries, he had never persecuted them. According to Colonel Anthony Durnford, the mission stations in Zululand had converted only a handful of Africans, âas the king considers that the moment a man becomes a Christian he is no use. Indeed he is right in his own point of view, as the few supposed Christians are an idle useless lot.â79 In all likelihood the missionaries decided to quit Zululand on the advice of Shepstone, who warned them of an impending âpolitical crisis.â

Frereâs propaganda campaign against the Zulu was briefly sidetracked in the early months of 1878 when the lieutenant governor of Natal, Sir Henry Bulwer, intervened to defuse the boundary dispute between the Transvaal Boers and the Zulu kingdom. Bulwer urged Frere and Shepstone to avoid rushing into a war against the Zulu. As Bulwer put it, âWe are looking to different objectsâI to the termination of the dispute by peaceful settlement, you to its termination by the overthrow of the Zulu kingdom.â80 Frere reluctantly agreed to Bulwerâs request, and a boundary commission was assembled at Rorkeâs Drift in March and April to gather evidence on the merits of the various claims. On June 20, 1878, the commissioners delivered their final report to Frere, which awarded the bulk of the disputed territory to the Zulu. For Frere the commission report was most unwelcome and undermined his case for war. According to the historian Ian Knight, âIt flatly contradicted the impression that [Frere] had carefully

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Central Africa | East Africa |

| North Africa | Southern Africa |

| West Africa | Algeria |

| Egypt | Ethiopia |

| Kenya | Nigeria |

| South Africa | Sudan |

| Zimbabwe |

Goodbye Paradise(3798)

Men at Arms by Terry Pratchett(2832)

Tobruk by Peter Fitzsimons(2507)

Borders by unknow(2301)

Arabs by Eugene Rogan(2292)

Pirate Alley by Terry McKnight(2217)

Belonging by Unknown(1854)

More Than Words (Sweet Lady Kisses) by Helen West(1853)

It's Our Turn to Eat by Michela Wrong(1723)

The Biafra Story by Frederick Forsyth(1653)

The Source by James A. Michener(1602)

Botswana--Culture Smart! by Michael Main(1597)

Coffee: From Bean to Barista by Robert W. Thurston(1538)

A Winter in Arabia by Freya Stark(1534)

Gandhi by Ramachandra Guha(1528)

The Falls by Unknown(1520)

Livingstone by Tim Jeal(1482)

The Shield and The Sword by Ernle Bradford(1402)

Africa: Altered States, Ordinary Miracles by Richard Dowden(1381)