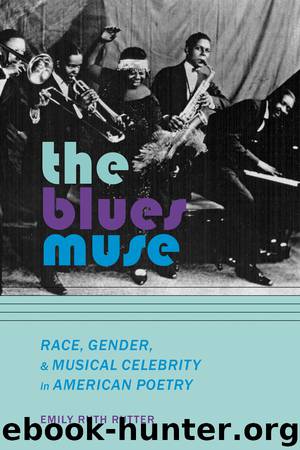

The Blues Muse by Emily Ruth Rutter

Author:Emily Ruth Rutter

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780817391973

Publisher: University of Alabama Press

and I

wake

up mumbling at the cross

roads/ my head

hung

down and I. Crying

poison/whips

hissed-screamed

in my past. And

the windows/ painted

with blood in my soul

crack. As he shouts

my future in a half

cry/half

late evening moon31

Plumpp’s enjambed lines require readers to consider the individual parts of his fractured phrases and to simultaneously glean dual meanings from them, such as in the lines “mumbling at the cross / roads.” On the one hand, this line refers to the choice that Johnson supposedly made between the security of Christian salvation (“mumbling at the cross”) and the renunciation of his faith that allowed him to gain artistic prowess playing the so-called devil’s music. On the other, Plumpp portrays Johnson as the guardian of the “cross / roads,” a sort of embodiment of the devil himself, whom the speaker must now reckon with in order to gain the ability to sing the blues. In the process, Plumpp implies the symbolic universality of the “crossroads” as a representation of the existential choices as well as the incumbent sacrifices that all artists (including Plumpp) must make in order to realize artistic aspirations. Thus, by the poem’s end, the speaker makes his own Faustian bargain and resolves to “Crawl a thousand / steps/ for his voice,” conjuring Johnson’s ghost in the twice-repeated final lines: “Hell / hounds on my trail.”32

Tony Bolden rightly asserts that Plumpp’s “singular achievement has been his ability to treat blues and jazz music as prisms of philosophical thought, while capturing the verve of the music on the printed page.”33 Plumpp’s poetics exemplify a blues aesthetic reminiscent of Johnson’s songs; at the same time, he is equally attentive to the stanzaic and linguistic textures of the printed page. Perhaps most importantly, “Robert Johnson” maintains the relevance of the epistemological framework that the blues conveys, a framework developed by working-class African Americans that stands in implicit opposition to white hegemony. Yet Plumpp also resurrects Johnson, rather stereotypically, as the embodiment of his haunting lyrics, revealing the endemic nature of such a perception during the second-wave blues revival, as well as the persistence of this interpretation of blues authenticity more generally. As Pearson lamented in 1992, “Apparently, it is impossible to convince anyone that blues songs do not mirror the singer’s own experience; nor is it possible to deter people from nurturing their own image of Johnson as satanist, genius, outsider, and inventor of rock and roll.”34 Of course, teasing out the man from the myths is more difficult with Johnson than perhaps any other blues musician because the facts of his life have eluded historians and musicologists for decades. Still, as Plumpp invokes Johnson as his blues muse—artistic catalyst, subject of praise, and vehicle to celebrate the blues—he mostly shores up, rather than complicates, mainstream images of Johnson.35

“On His Way to the Spirit World”

While Plumpp’s Johnson portrait comprises a few dozen lines, John Sinclair’s 2002 collection Fattening Frogs for Snakes: Delta Sound Suite36 includes a series of Johnson tributes that reference many of the most well-known compositions in Johnson’s twenty-nine song oeuvre:

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African | Asian |

| Australian & Oceanian | Canadian |

| Caribbean & Latin American | European |

| Jewish | Middle Eastern |

| Russian | United States |

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12360)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(7744)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7313)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5747)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(5738)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5406)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5067)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4924)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(4713)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(4560)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(4541)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(4508)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(4433)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(4084)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4013)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(3999)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(3982)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3965)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3838)