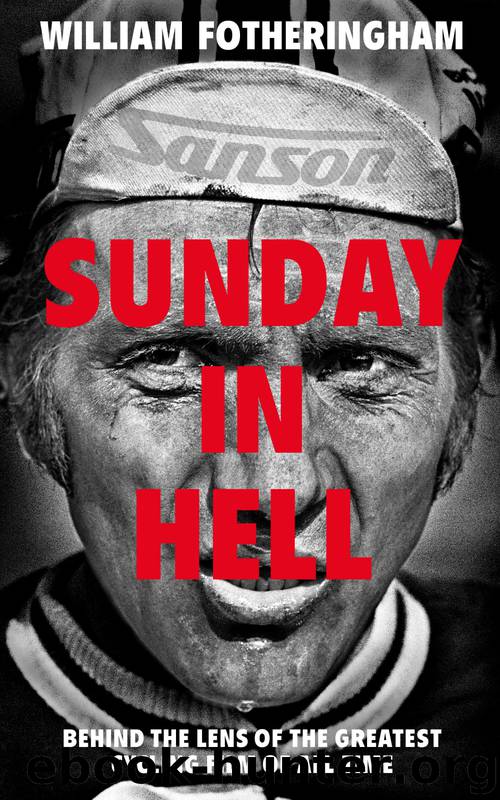

Sunday in Hell by William Fotheringham

Author:William Fotheringham

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Random House

The dramatic shift in intensity when the set-pieces are reached is an integral part of Classic racing – the first cobbled sections en route to Roubaix; the succession of little hills known as the capi in Milan–San Remo – and Leth captures this with the timpani roll, the abrupt emergence of the solo cello as De Vlaeminck makes his move and is caught by Walter Planckaert and Ludo Dierickx, the switches between the extended sequence showing the motorbikes jostling in front of the Gypsy, and slow motion of the peloton, biceps vibrating in agonising close-up in a chaos of crowd noise, car horns. The dusty panorama places it all in context.

De Vlaeminck is riding in the classic manner: getting to the front and staying there. ‘In Paris–Roubaix, the break can go anywhere,’ the 1994 winner Andrei Tchmil told me. ‘On the tarmac, on the pavé, after a crash. You can’t expect anything so it’s better to be in front all the time. Then you have to understand the moment, sense that the riders who have gone are the right ones. It’s just down to intuition.’

‘The strongest men stay out of trouble because they always stay at the front,’ another specialist said. ‘When riders are tired, they ride on the edge of the cobblestones and get punctures.’ The strong men often favour the crown of the road – as Walter Godefroot did – with the entire width to play with, albeit with the risk that if the cobbles fall away steeply all of a sudden, the front wheel can be lost. In the wet, the crown of the road is a dangerous place to ride. ‘When you are strong, you can lay off the wheel in front’ – leave a small gap – ‘and see where you are going. When you are tired, if you don’t ride on the wheels you get dropped, so you ride blind and you can’t see what’s coming up. You just have to pray.’

Moser’s tactic for Paris–Roubaix was the opposite to the one favoured by De Vlaeminck: ‘Wait, and make as few mistakes as possible. You have to use the terrain, or you forget where you are. The difference in this race is a mental one. It’s a waiting game, to the very end. The problem is that when you feel strong, you tend to be tempted to press just a little bit harder on the pedals. The risk then is that you end up devoid of strength in the end. Sometimes, if you are slightly below the best physically, you use your strength differently, you save what you’ve got, and you can win.’

The riders faced a common issue in the 1976 race, which is far less of a factor now: the difficulty of getting spare wheels and bikes when – not if – they punctured or crashed. ‘The bikes are practically the same as in 1976 but what’s different is that in almost every one of the cobbled zones, pretty much every team has organised for people to be there with spare wheels and bikes,’ says Jean-François Pescheux.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Shoe Dog by Phil Knight(5270)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(4970)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3963)

How to Read Water: Clues and Patterns from Puddles to the Sea (Natural Navigation) by Tristan Gooley(3469)

Running Barefoot by Amy Harmon(3448)

I'll Give You the Sun by Jandy Nelson(3448)

Crazy Is My Superpower by A.J. Mendez Brooks(3401)

How to Read Nature by Tristan Gooley(3341)

How Music Works by David Byrne(3272)

The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse by Charlie Mackesy(3131)

The Fight by Norman Mailer(2943)

Seducing Cinderella by Gina L. Maxwell(2645)

Cuba by Lonely Planet(2635)

Accepted by Pat Patterson(2371)

Going Long by Editors of Runner's World(2362)

The Unfettered Mind: Writings from a Zen Master to a Master Swordsman by Takuan Soho(2311)

Backpacker the Complete Guide to Backpacking by Backpacker Magazine(2248)

The Happy Runner by David Roche(2239)

Trail Magic by Trevelyan Quest Edwards & Hazel Edwards(2184)