Silk, the Thread That Tied the World by Burton Anthony;

Author:Burton, Anthony; [Burton, Anthony;]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: DESIGN / Fashion & Accessories

ISBN: 9781526780928

Publisher: PenSword

Published: 2020-04-02T00:00:00+00:00

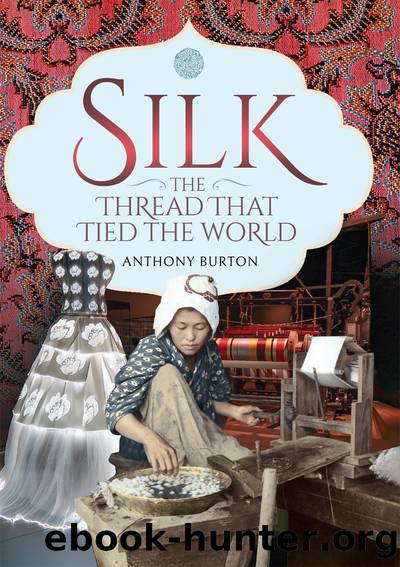

An English figured silk waistcoat panel from the early eighteenth century in the Smithsonian Design Museum.

One type of cloth that became very popular was figured silk. It was said to have been introduced by three specific weavers â Lauson, Manscot and Monceaux â while the designs were all supplied by the artist, Beaudoin. Another refugee workman brought with him the technology for adding lustre to silk taffeta. This must have been especially galling to the manufacturers of Lyon as black lustrings had been such a major part of their export trade to London that the cloth actually became known as English taffeta. Now the material could be made to the same high standard in Spitalfields. By 1692, the trade had become so well established that a charter was granted to the newly formed Royal Lustring Company. To add insult to injury as far as the French were concerned, the new Company managed to persuade parliament that the local product was now so good that imports from France should be prohibited as they were no longer needed. It is a rather odd argument â if the English material was that brilliant why did it need protecting from foreign competition?

The London silk workers had always struggled to compete with imports from France, and as early as 1696, measures were taken to protect the home industry, by either applying high taxes or even by outright banning of imports. An Act of that year bemoaned the loss of revenue caused by importing silk cloth and claiming it was no longer necessary as it could now be manufactured in England by âthe Royal Lustring Company to as great perfection as in any other countryâ. But high import duties might have deterred legal trade, but there was still an unsatisfied demand for luxurious French silks and the same Act deplored âthe importation of such foreign silks without paying the duties charged thereon which have been frequently eluded by the subtle practices of evil disposed persons.â Or in plain English â when tariffs are high, smugglers thrive.

To many, smuggling seemed a harmless enough activity, to which the community turned a blind eye, as Kipling wrote in A Smugglerâs Song:

Five and twenty ponies

Trotting through the dark â

Brandy for the Parson. âBaccy for the Clerk

Laces for a lady, letters for a spy.

Watch the wall my darling while the Gentlemen go by.

But they were by no means all gentlemen, nor indeed gentle men. There seems to have been a distinction between the smugglers of the south west of England and those of the south east. The former seem often to have been fishermen making a bit on the side and otherwise were regarded as respectable members of the community. Those of the south east were often very different, in effect well organised criminal gangs. The south west was not a wealthy area, and tobacco and brandy probably were the most commonly smuggled goods as in the Kipling poem. The market for smuggled silk was in the wealthier area of London and its surroundings, and it was through the south east ports that most of the silk was brought in.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Wonder by R.J. Palacio(8267)

Unlabel: Selling You Without Selling Out by Marc Ecko(3471)

Mastering Adobe Animate 2023 - Third Edition by Joseph Labrecque(3414)

Ogilvy on Advertising by David Ogilvy(3331)

Hidden Persuasion: 33 psychological influence techniques in advertising by Marc Andrews & Matthijs van Leeuwen & Rick van Baaren(3292)

Drawing Cutting Edge Anatomy by Christopher Hart(3290)

POP by Steven Heller(3230)

The Pixar Touch by David A. Price(3210)

The Code Book by Simon Singh(2857)

The Art of War Visualized by Jessica Hagy(2839)

The Curated Closet by Anuschka Rees(2803)

Slugfest by Reed Tucker(2803)

Rapid Viz: A New Method for the Rapid Visualization of Ideas by Kurt Hanks & Larry Belliston(2729)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2687)

The Wardrobe Wakeup by Lois Joy Johnson(2635)

365 Days of Wonder by R.J. Palacio(2626)

Keep Going by Austin Kleon(2598)

Tell Me More by Kelly Corrigan(2520)

Tattoo Art by Doralba Picerno(2487)