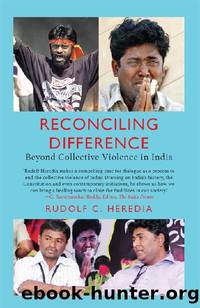

Reconciling Difference: Beyond Collective Violence in India by Rudi Heredia

Author:Rudi Heredia [Heredia, Rudi]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Published: 2021-02-22T00:00:00+00:00

Contextualizing Gandhi

Indic civilizationâs experience with Islam was very different from that of the West. In coastal areas, especially in the south, Muslim Arabs came as traders, and the exchange was largely peaceful. In the north, the Muslims came as conquerors: the Mughal Empire, which flowered into a composite culture, but was finally overtaken by the British.

The Great Uprising of 1857 almost succeeded in ending the East India Company rule, and the Hindu-Muslim unity it demonstrated was praised even by Savarkar who wrote The First Indian War of Independence, 1857. (1970, 1st 1908) The divide-and-rule policy employed by the British thereafter finally ended with the Partition. However, the trauma of colonial rule by an alien and distant civilization precipitated an existential crisis in the self-understanding of the Indian peoples.

In the 18th and 19th centuries when one in three British men were married to Indian women, (Dalrymple 2002) the exchange was far more equal, appreciative and adaptive, and there might have been the possibility of fusion and hybridity contrary to Kiplingâs idea that âEast is East and West is West and never the twain shall meetâ. Dalrymple argues that The White Mughals (Dalrymple 2007) might have changed that. However, the barbarities committed by both sides during the Great Rebellion of 1857 caused too much distance and mistrust between them. The freedom movement picked up the pieces and struggled not just for swatantrata, independence from British rule, but rather for swaraj, self-rule, beginning with ruling the personal âselfâ as the basis for ruling the collective âselfâ.

Gandhi was its architect and dominant force. His was a new vision in a new conceptual language that drew from the rich heritage of Indic tradition that challenged the very basis of the founding assumptions of Imperial rule, not from within but from without. Little wonder that the white sahibs did not understand, nor know how to cope with him. But neither have the brown sahibs to date. Many of the leaders of the freedom movement did not quite comprehend Gandhiâs âswarajâ that was to be founded on ahimsa, satya and satyagraha, (non-violence, truth and truth force) much less its implications for personal and social living.

In South Africa, Gandhiâs fight for the rights of Indians there espoused non-violent passive resistance, better categorized as civil disobedience. His approach was twofold: selected demonstrations of collective non-violent civil disobedience against unjust laws; and the Tolstoy Farm for his followers to live, learn and internalize their commitment to non-violence and its implications. Here his perspectives on a non-violent mass movement against an intransigent opposition matured into what he would call âahimsaâ in the freedom struggle in India.

When Gandhi returned from South Africa in 1915, he redirected the efforts of the Indian National Congress, which was by then the most prominent movement for Independence, towards a mass struggle for swaraj, committed to ahimsa and satyagraha. Indeed, for Gandhi, the personal was the political. He began with peaceful âcivil disobedienceâ in South Africa inspired by the counter-culture from the West: the ideas of Leo Tolstoy, John Ruskin and Henry David Thoreau.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Born to Run: by Christopher McDougall(7120)

The Leavers by Lisa Ko(6945)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5408)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5363)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5173)

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(5163)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4290)

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber(4177)

Never by Ken Follett(3934)

Goodbye Paradise(3798)

Livewired by David Eagleman(3762)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3368)

A Dictionary of Sociology by Unknown(3071)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3057)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(3014)

The Club by A.L. Brooks(2919)

Will by Will Smith(2905)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2843)

People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory by Dr. Brian Fagan & Nadia Durrani(2726)