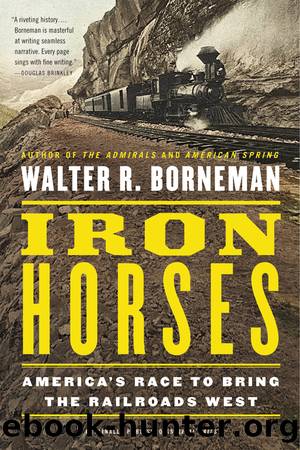

Iron Horses by Walter R. Borneman

Author:Walter R. Borneman [R. BORNEMAN, WALTER]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History / United States / 19th Century, History / United States / General

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Published: 2014-11-18T00:00:00+00:00

So, the corporate shell of the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, with the solid financial backing of both the Santa Fe and the Frisco, continued to build westward from Flagstaff in the summer of 1882. By September 1, the railhead had reached Williams—a bustling settlement named for mountain man and trapper “Old Bill” Williams. Land speculators anticipated the railroad’s advance, and their optimism was rewarded when Williams was initially made a division point.

West of Williams, the terrain got tougher again. The line dropped 2,000 feet in elevation along a 3 percent grade to reach Ash Fork. The chief difficulty was in Johnson Canyon. Here workers were forced to blast two 150-foot cuts and a 328-foot tunnel through hardened lava flows.

It was dangerous work. On one hot summer day, two and one-half tons of powder were tamped into drill holes in preparation for the usual blast. Tamping with a copper or bronze rod was the correct procedure, but someone picked up an iron bar by mistake. It struck the hard rock with a spark that ignited the powder and caused a premature explosion. Six workers were killed and another three seriously injured. A young boy riding nearby in a mule cart became a seventh victim. The cart was totally demolished, but somehow the mule escaped unharmed.

J. T. Simms was the tunnel contractor, and he worked crews from both ends. Once completed in the spring of 1882, the Johnson Canyon Tunnel was a work of art. Because of loose rock, the tunnel was lined with stonework retaining walls topped with sections of boilerplate that arched across the roof.

The Santa Fe continued to use this tunnel until 1959. The fact that it was the only tunnel on the Santa Fe line between Cajon Pass and Raton Pass is a testament to the less mountainous terrain of the 35th parallel route when compared to lines in the Rockies or Sierras. (The Crookton Cutoff on the main line now bypasses this entire section of Johnson Canyon and has reduced grades to about 1 percent.)

Once the Johnson Canyon Tunnel and two nearby viaducts across arroyos were ready for rails, the tracklayers quickly pushed westward to Seligman, which eventually replaced Williams as the division point. Beyond Seligman lay Chino Wash, a normally dry expanse of arroyos that had the tendency to fill with raging flash floods when the rains of July and August dumped moisture from the south onto the rocky terrain.

Construction crews had already learned the lesson of the infamous summer monsoons of the Arizona desert the hard way. Flash floods and high water destroyed portions of the Southern Pacific’s new line across Cienega Wash, east of Tucson, in the summer of 1880. The Atlantic and Pacific experienced similar problems and was forced to rebuild sections of roadbed around Holbrook the following year. Finally getting wise to nature’s vagaries, the Atlantic and Pacific opted to construct a 600-foot iron viaduct across the usually dry flats of Chino Wash.

From there the line headed northwest to a more reliable and less tumultuous source of water.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Small Unmanned Fixed-wing Aircraft Design by Andrew J. Keane Andras Sobester James P. Scanlan & András Sóbester & James P. Scanlan(32141)

Navigation and Map Reading by K Andrew(4554)

Endurance: Shackleton's Incredible Voyage by Alfred Lansing(3845)

Wild Ride by Adam Lashinsky(1659)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(1615)

The Box by Marc Levinson(1596)

Top 10 Prague (EYEWITNESS TOP 10 TRAVEL GUIDES) by DK(1568)

The Race for Hitler's X-Planes: Britain's 1945 Mission to Capture Secret Luftwaffe Technology by John Christopher(1526)

The One Percenter Encyclopedia by Bill Hayes(1463)

Girls Auto Clinic Glove Box Guide by Patrice Banks(1363)

Trans-Siberian Railway by Lonely Planet(1345)

Looking for a Ship by John McPhee(1320)

Batavia's Graveyard by Mike Dash(1302)

Fighting Hitler's Jets: The Extraordinary Story of the American Airmen Who Beat the Luftwaffe and Defeated Nazi Germany by Robert F. Dorr(1301)

Troubleshooting and Repair of Diesel Engines by Paul Dempsey(1284)

Bligh by Rob Mundle(1274)

TWA 800 by Jack Cashill(1253)

The Great Halifax Explosion by John U. Bacon(1229)

Ticket to Ride by Tom Chesshyre(1229)