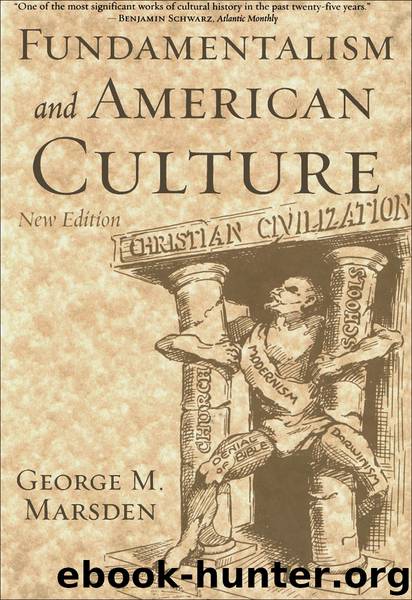

Fundamentalism and American Culture by Marsden George M.;

Author:Marsden, George M.;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Published: 2006-08-25T04:00:00+00:00

XXI. Epilogue: Dislocation, Relocation, and Resurgence: 1925–1940

It would be difficult to overestimate the impact of “the Monkey Trial” at Dayton, Tennessee, in transforming fundamentalism. William Jennings Bryan’s ill-fated attempt in the summer of 1925 to slay singlehanded the prophets of Baal brought instead an outpouring of derision. The rural setting, so well suited to the stereotypes of the agrarian leader and his religion, stamped the entire movement with an indelible image. Very quickly, the conspicuous reality of the movement seemed to conform to the image thus imprinted and the strength of the movement in the centers of national life waned precipitously.

It was part of the liberals’ contention that the issues separating them from the fundamentalists were determined by social forces. As Shailer Mathews put it in The Faith of Modernism, “the differences between these two types of Christians are not so much religious as due to different degrees of sympathy with the social and cultural forces of the day.”1 While the fundamentalists argued that the acceptance or rejection of unchanging truth was at issue, the modernists insisted that the perception of truth was inevitably shaped by cultural circumstances. By modernist definition fundamentalists were those who for sociological reasons held on to the past in stubborn and irrational resistance to inevitable changes in culture.

The scene at Dayton in 1925 was unsurpassable as a confirmation of this interpretation. Here were the elements of a great American drama—farce, comedy, tragedy, and pathos. Mark Twain and H. L. Mencken in collaboration could hardly have scripted it better. This bizarre episode, wired around the world with a maximum of ballyhoo, would have far more impact on the popular interpretation of fundamentalism than all the arguments of preachers and theologians.

The central theme was, inescapably, the clash of two worlds, the rural and the urban. In the popular imagination, there were on the one side the small town, the backwoods, half-educated yokels, obscurantism, crackpot hawkers of religion, fundamentalism, the South, and the personification of the agrarian myth himself, William Jennings Bryan. Opposed to these were the city, the clique of New York-Chicago lawyers, intellectuals, journalists, wits, sophisticates, modernists, and the cynical agnostic Clarence Darrow. These images evoked the familiar experiences of millions of Americans who had been born in the country and moved to the city or who were at least witnessing the dramatic shift from a predominantly rural to a predominantly urban culture. Main Street, Sinclair Lewis’s famous portrait of the dullness of smalltown America, had since its publication in 1920 furnished a potent symbol of the rural America from which people of education and culture escaped. Dayton surpassed all fiction in dramatizing the symbolic last stand of nineteenth-century America against the twentieth century.

Since 1923 several Southern states had adopted some type of anti-evolution legislation, and similar bills were pending throughout the nation. The law passed in Tennessee in the spring of 1925 was the strongest. It banned the teaching of Darwinism in any public school. This law was immediately tested by a young Dayton biology teacher, John Scopes.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Gnostic Gospels by Pagels Elaine(2400)

Jesus by Paul Johnson(2230)

Devil, The by Almond Philip C(2206)

The Nativity by Geza Vermes(2116)

The Psychedelic Gospels: The Secret History of Hallucinogens in Christianity by Jerry B. Brown(2073)

Forensics by Val McDermid(1979)

Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief by Lawrence Wright(1884)

Going Clear by Lawrence Wright(1873)

Barking to the Choir by Gregory Boyle(1731)

Old Testament History by John H. Sailhamer(1714)

Augustine: Conversions to Confessions by Robin Lane Fox(1688)

The Early Centuries - Byzantium 01 by John Julius Norwich(1655)

A History of the Franks by Gregory of Tours(1639)

The Bible Doesn't Say That by Dr. Joel M. Hoffman(1611)

Dark Mysteries of the Vatican by H. Paul Jeffers(1607)

A Prophet with Honor by William C. Martin(1603)

by Christianity & Islam(1564)

The First Crusade by Thomas Asbridge(1539)

The Amish by Steven M. Nolt(1491)