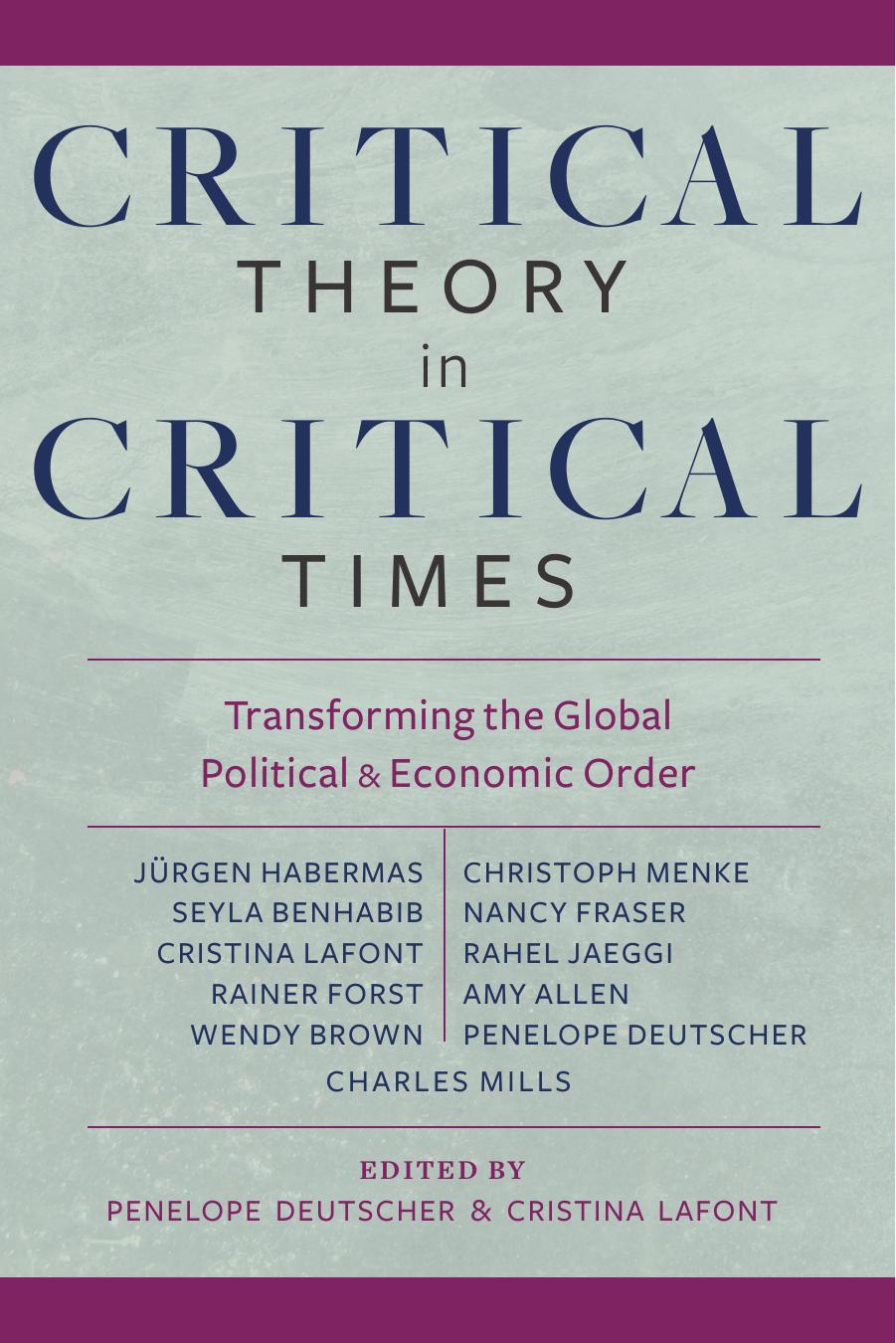

Critical Theory in Critical Times: Transforming the Global Political and Economic Order by Penelope Deutscher & Cristina Lafont

Author:Penelope Deutscher & Cristina Lafont

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Tags: Law, Jurisprudence, Philosophy, Movements, Critical Theory, Political, Political Science, History & Theory

Publisher: Columbia University Press

Published: 2017-04-04T00:00:00+00:00

BACKGROUND CONDITIONS

So far, I have been elaborating a fairly orthodox definition of capitalism, based on four core features that seem to be “economic.” I have effectively followed Marx in looking behind the commonsense perspective, which focuses on market exchange, to the “hidden abode” of production. Now, however, I want to look behind that hidden abode, to see what is more hidden still. Marx’s account of capitalist production only makes sense when we start to fill in its background conditions of possibility. So the next question will be, What must exist behind these core features in order for them to be possible?

Marx himself broaches a question of this sort near the end of volume 1 of Capital, in the chapter on so-called “primitive” or original accumulation.4 Where did capital come from? he asks. How did private property in the means of production come to exist, and how did the producers become separated from them? In the preceding chapters, Marx had laid bare capitalism’s economic logic in abstraction from its background conditions of possibility, which were assumed as simply given. But it turned out that there was a whole backstory about where capital itself comes from—a rather violent story of dispossession and expropriation. Moreover, as David Harvey has stressed, this backstory is not located only in the past, at the “origins” of capitalism.5 Expropriation is an ongoing, albeit unofficial, mechanism of accumulation, which continues alongside the official mechanism of exploitation—Marx’s “front story,” so to speak.

This move, from the front story of exploitation to the backstory of expropriation, constitutes a major epistemic shift, which casts everything that went before in a different light. It is analogous to the move Marx makes earlier, near the beginning of volume 1, when he invites us to leave behind the sphere of market exchange, and the perspective of bourgeois common sense associated with it, for the hidden abode of production, which affords a more critical perspective. As a result of that first move, we discover a dirty secret: accumulation proceeds via exploitation. Capital expands, in other words, not via the exchange of equivalents, as the market perspective suggests, but precisely through its opposite—via the noncompensation of a portion of workers’ labor time. Similarly, when we move, at the volume’s end, from exploitation to expropriation, we discover an even dirtier secret: behind the sublimated coercion of wage labor lie overt violence and outright theft. In other words, the long elaboration of capitalism’s economic logic, which constitutes most of volume 1, is not the last word. It is followed by a move to another perspective, the dispossession perspective. This move to what is behind the “hidden abode” is also a move to history—and to what I have been calling the background “conditions of possibility” for exploitation.

Arguably, however, there are other, equally momentous epistemic shifts that are implied in Marx’s account of capitalism but are not developed by him. These moves, to abodes that are even more hidden, are still in need of conceptualization. They need to be written up

Download

Critical Theory in Critical Times: Transforming the Global Political and Economic Order by Penelope Deutscher & Cristina Lafont.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19058)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12187)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8894)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6877)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6267)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5789)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5737)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5500)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5432)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5216)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5144)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5081)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4954)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4921)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4780)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4742)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4709)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4502)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4484)