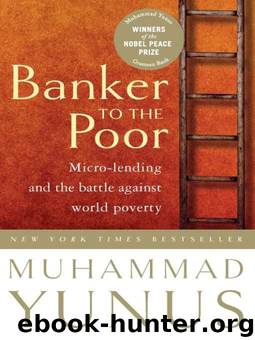

Banker to the Poor: Micro-Lending and the Battle Against World Poverty by Muhammad Yunus

Author:Muhammad Yunus [Yunus, Muhammad]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Business

ISBN: 9781586485467

Google: 41sGGHUE5N4C

Barnesnoble:

Goodreads: 10812515

Publisher: Amazon Digital Services Inc.

Published: 1991-01-01T05:00:00+00:00

After 1986, when Grameen made it clear to the World Bank that we would not let it tell us how to run our business, the bank decided to try to form its own micro-credit organization in Bangladesh by combining our methodology with those of a number of other micro-credit programs. I thought the idea was wholly unrealistic. Ultimately, the Bangladesh government took our advice and resisted the World Bank initiative, but the World Bank did not learn anything from the process. On the contrary, it removed the name “Bangladesh” from the rejected project document and offered it to the Sri Lankan government instead.

My less-than-pleasant experience with the World Bank spurred me to learn as much as I could about development agencies. One observation that became increasingly apparent is that multilateral aid institutions have a lot of money to disburse. Officials determine target amounts for each country. The more money officials manage to give out, the better grade they receive as lending officers. Therefore young, ambitious officers of a donor agency will choose the projects with the biggest price tag. By moving a lot of money, their name moves up the promotion ladder.

In my line of work, I have often witnessed the desperation of donor agency officials to give away ever-larger sums of money to Bangladesh. They will do almost anything to achieve this, including bribing government officials and politicians either directly or indirectly. For instance, they will rent newly built, expensive houses owned by government officials or invite them on attractive foreign trips under the guise of official workshops and conferences. Consultants, suppliers, and potential contractors often facilitate this bribing mechanism. After all, they are the ones who most benefit from projects funded by donors.

One research institution in Bangladesh estimates that of the more than $30 billion in foreign donor assistance received in the past twenty-six years, 75 percent was not spent in Bangladesh. It was spent on equipment, commodities, and consultants from the donor country itself. Most rich nations use their foreign aid budget mainly to employ their own people and to sell their own goods, with poverty reduction as an afterthought. The 25 percent that is spent in Bangladesh usually goes straight to a tiny elite of local suppliers, contractors, consultants, and experts. Much of this money is used by these elites to buy foreign-made consumer goods, which is of no help to our country’s economy or workforce. And there is a general belief that a good chunk of donor money ends up as kickbacks to officials and politicians who have helped make purchase decisions and sign contracts.

The situation is the same in all countries receiving aid, which amounts to $50—$55 billion a year. Aid-funded projects create massive bureaucracies, which quickly become corrupt and inefficient, incurring huge losses. In a world that trumpets the superiority of the market economy and free enterprise, aid money still goes to expand government spending, often acting against the interests of the market economy.

Most foreign aid goes to building roads, bridges, and so forth, which are supposed to help the poor “in the long run.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19053)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12187)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8893)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6877)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6265)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5787)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5737)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5500)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5431)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5215)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5141)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5081)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4954)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4921)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4780)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4741)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4709)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4502)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4484)