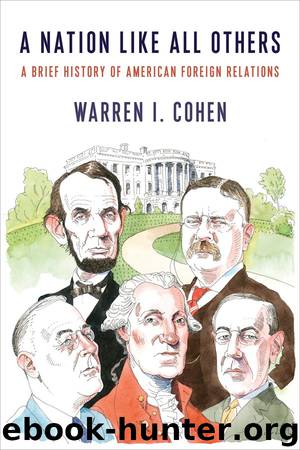

A Nation Like All Others: A Brief History of American Foreign Relations by Warren I. Cohen

Author:Warren I. Cohen

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History, United States, General, Political Science, American Government, International Relations

Publisher: Columbia University Press

Published: 2018-03-06T00:00:00+00:00

14

VIETNAM AND THE LESSONS OF GREAT POWER ARROGANCE

America’s war in Vietnam was an example of great power arrogance. Neither American leaders nor American scholars knew or cared much about the people of Vietnam, their history, their culture, or their aspirations. Vietnam was of no intrinsic importance to the United States. In the years when France controlled Indochina, it allowed little foreign involvement in the region’s economy. American business acquired no stake there. The area was potentially rich in natural resources, but there was nothing there that could not be obtained elsewhere or that the locals could afford to deny to the world market. Similarly, the region was of minimal strategic importance. A case could be made for keeping Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam—or any place else on earth—from being controlled by an adversary, whether Japan in 1941 or China or the Soviet Union in the Cold War. French control was desirable, but if all of Indochina were hostile to the United States, the shift in the world balance of power would be imperceptible. No vital American interest would be threatened. Nonetheless, more than fifty thousand Americans gave their lives in a war in Indochina, as did millions of Cambodians, Laotians, and Vietnamese.

Once a nation develops the ability to project its power to distant regions of the globe, to intervene in the affairs of other peoples, the temptation to do so seems nearly irresistible—at least until its leaders are sobered by disaster. American power in the first two decades after World War II, relative and absolute, was extraordinary. No place in the world was beyond the reach of the United States. And for American policymakers the lessons of the past demonstrated that their nation had a responsibility to use its power to stop aggressors and to thwart those who would extend totalitarian systems.

American leaders discovered Indochina early in World War II, when the Japanese intruded on the French empire. Japanese pressures on Southeast Asia worried Franklin Roosevelt, who feared their maneuvers would distract the British from the task of containing Germany in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. Toward the end of the war, when the retreat of Japanese forces was imminent, Roosevelt suggested that the people of Indochina be put under a UN trusteeship rather than be subjected again to French imperialism. The few Americans who reached the area before the end of the war discovered a well-organized resistance movement that had harassed the Japanese and had no intention of submitting to the French. In Vietnam in particular, the will to independence was strong and deemed worthy of American support. Indeed, the leader of the Vietnamese resistance, Ho Chi Minh, worked with American intelligence operatives on the eve of Japan’s surrender.

When the war ended, the French returned, determined to reassert their control. French leaders warned Washington that opposition to French suppression of the Vietnamese independence movement would alienate the French people, strengthen the French Communists, and, conceivably, drive France into the arms of the Soviets. Ho invoked Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence, to no avail.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19052)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12187)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8893)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6877)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6264)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5786)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5737)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5499)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5431)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5215)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5141)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5081)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4954)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4921)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4779)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4741)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4706)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4502)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4484)