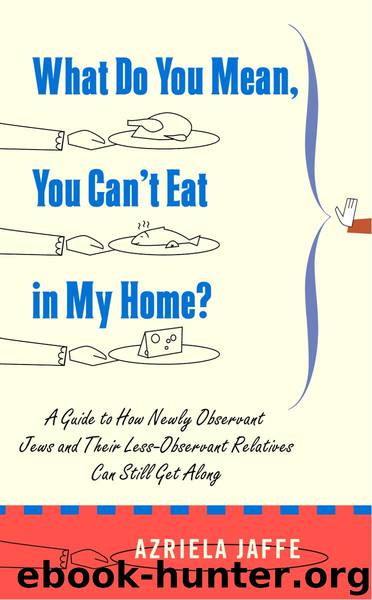

What Do You Mean, You Can't Eat in My Home? by Azriela Jaffe

Author:Azriela Jaffe

Language: eng

Format: epub

Published: 2018-10-31T16:00:00+00:00

6. Why are women “exempt” from fulfilling time-bound commandments in the Torah, such as putting on tefillin? What if they want to do them anyway?

In traditional Jewish law and custom, the woman is the primary caregiver in the family. Therefore, according to the Mishnah, she is exempt from any religious requirement that would get in the way of taking care of her children properly. (A woman who is, for whatever reason, not a caregiver is also exempt from time-bound commandments.) Jewish law is not set up so that people face conflicting obligations and have to choose which one to fulfill. Men are required to pray at specific times of the day. Women are not similarly required to do so because Jewish law acknowledges that a woman may be occupied with taking care of her children when it is time to pray. This does not imply that praying is more important than taking care of children, or that taking care of children is more important than praying. It simply acknowledges that men and women fulfill their religious obligations in different ways. In fact, according to halachah, women should make every effort to pray at the proper times, particularly women who for whatever reason do not have family responsibilities. So what happens nowadays, when men and women share breadwinning and caregiving responsibilities? There’s nothing wrong with this, but it doesn’t change the Mishnah’s view that, in the ideal world, the woman is the primary caregiver.

There is another, slightly more esoteric reason for a woman’s exemption from time-bound religious obligations. Praying and performing religious rituals, such as putting on a tallis and tefillin, are designed to create a greater spiritual connection between God and man. As we discussed earlier, traditional Jewish theology says that women possess an inherent spiritual connection to God that men do not have. Therefore, women are not required to perform rituals designed to create this greater spiritual connection to God—but in some instances they may do so if they wish. Saying the blessing for the lulav and esrog on Sukkos and hearing the shofar on Rosh Hashanah are examples of time-bound obligations that women were not initially required to do, but that they have, over time, taken upon themselves anyway.

You can mention to your family that the Torah is not saying “Women can’t do this,” but, rather, “Women don’t have to do this.” But non-Orthodox Jews will probably still think this sounds like discrimination, and it won’t be easy for you to help them see this any differently, even by explaining that modern, secular notions of “equality” have nothing to do with the way the Torah tells us that God wants men and women to serve Him. The Torah’s idea of respecting women is not putting them in the untenable situation of having to choose between caring for their children and praying to God.

7. Why can’t women be included in a minyan (prayer quorum often)?

8. Why can’t women serve as the prayer leader or the Torah reader in communal

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Haggadah | Hasidism |

| History | Holidays |

| Jewish Life | Kabbalah & Mysticism |

| Law | Movements |

| Prayerbooks | Sacred Writings |

| Sermons | Theology |

| Women & Judaism |

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. Frankl(2254)

The Secret Power of Speaking God's Word by Joyce Meyer(2253)

Mckeown, Greg - Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less by Mckeown Greg(2112)

MOSES THE EGYPTIAN by Jan Assmann(1972)

Unbound by Arlene Stein(1940)

Devil, The by Almond Philip C(1899)

The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English (7th Edition) (Penguin Classics) by Geza Vermes(1840)

I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith(1571)

Schindler's Ark by Thomas Keneally(1514)

The Invisible Wall by Harry Bernstein(1458)

The Gnostic Gospel of St. Thomas by Tau Malachi(1412)

The Bible Doesn't Say That by Dr. Joel M. Hoffman(1372)

The Secret Doctrine of the Kabbalah by Leonora Leet(1267)

The Jewish State by Theodor Herzl(1251)

The Book of Separation by Tova Mirvis(1224)

A History of the Jews by Max I. Dimont(1206)

The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible by Martin G. Abegg(1200)

Political Theology by Carl Schmitt(1187)

Oy!: The Ultimate Book of Jewish Jokes by David Minkoff(1104)