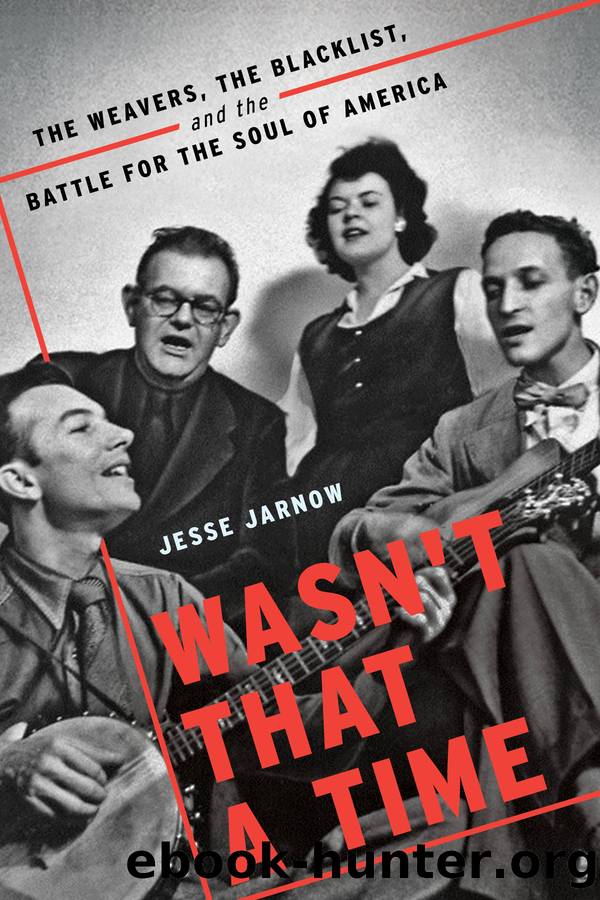

Wasn't That a Time by Jesse Jarnow

Author:Jesse Jarnow [JARNOW, JESSE]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Hachette Books

Published: 2018-11-06T00:00:00+00:00

Members of the Weavers didn’t often turn up at the Sunday jam sessions in Washington Square Park, but their presence was undeniable. For a few years when they lived nearby, Pete and Toshi had held the official permit themselves. The scene emerged almost imperceptibly a decade back with a core of People’s Songsters who played every weekend in agreeable weather through the spring, summer, and fall, and crammed into friendly apartments when jamming outside wasn’t tenable, maybe followed by dinner at Sam Wo’s in Chinatown.

More than the various social connections, the Weavers shaped the music as it was played. “Folk music” before, after, and during the Weavers, was a catch-all term, catching anything that might be deemed “ethnic” music, from Southern fiddlers to Ukrainian harmonizers. The Billboard’s “Folk Tunes & Talent” column still mostly tracked country stars like George Jones. But as soon as the Weavers regularized the uneven harmonies and arrangements of the Bahamian songs “Dig My Grave” and “Wreck of the John B,” they virtually invented a striking new way to occupy the concept.

This new unified idea of folk music was of the times, too, a mainstreaming process of the 1950s that contorted sounds and images and flavors into a melting pot, welcoming the old ideas to the atomic age. Politics removed, the Weavers created a rhythmic, harmonic, and musical standard for a new generation of musicians. Not that it all sounded like the Weavers.

The permit was good for Sunday afternoons, two to six p.m. From above, the scene that resulted might be observed as visualizations of literal circles of musicians scattered in the north part of the park around the fountain and Stanford White’s mock triumphal arch. Binding it together were the sing-alongs on staple numbers like “Blue-Tailed Fly” and “On Top of Old Smoky,” but more nuanced groups reigned on the fringes. There was a squad from the Jewish summer camps. There were political pickers in the Almanac tradition. There were mournful balladeers. There was a group, as well, of extremely serious musicians devoted to traditional American bluegrass, played in arrangements as authentic as possible. There was crossover in the players and the musicians they listened to. And if the Weavers weren’t responsible for many of them being there, Pete by himself surely was.

The pool of musicians that cut their teeth in Washington Square Park would cross into the Weavers’ musical circles in coming years. It wasn’t a singing labor movement at all. But it was singing. A lot of it. Rarely were the politics obvious. All that many shared, in fact, was the singing itself. The Weavers had hardly invented group singing, but it was one that they helped bring into the lexicon of secular American middle-class activity, from Pete’s song-leading on the hit “On Top of Old Smoky” single to every concert they gave from their Carnegie Hall reunion onward. That unity, without a specific message attached, could be heard differently by all, though certainly the Weavers (and many others) coded their music as they saw fit and hoped for the best.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3095)

Unfinished: A Memoir by Priyanka Chopra Jonas(2921)

Never by Ken Follett(2915)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(2324)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(2312)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(2101)

Will by Will Smith(2075)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(1777)

The Storyteller by Dave Grohl(1670)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(1586)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1580)

The Stranger in the Lifeboat by Mitch Albom(1561)

Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr(1450)

New Morning Mercies: A Daily Gospel Devotional by Paul David Tripp(1388)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(1350)

The Becoming by Nora Roberts(1344)

Crying in H Mart by Michelle Zauner(1332)

Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson(1322)

A Short History of War by Jeremy Black(1308)