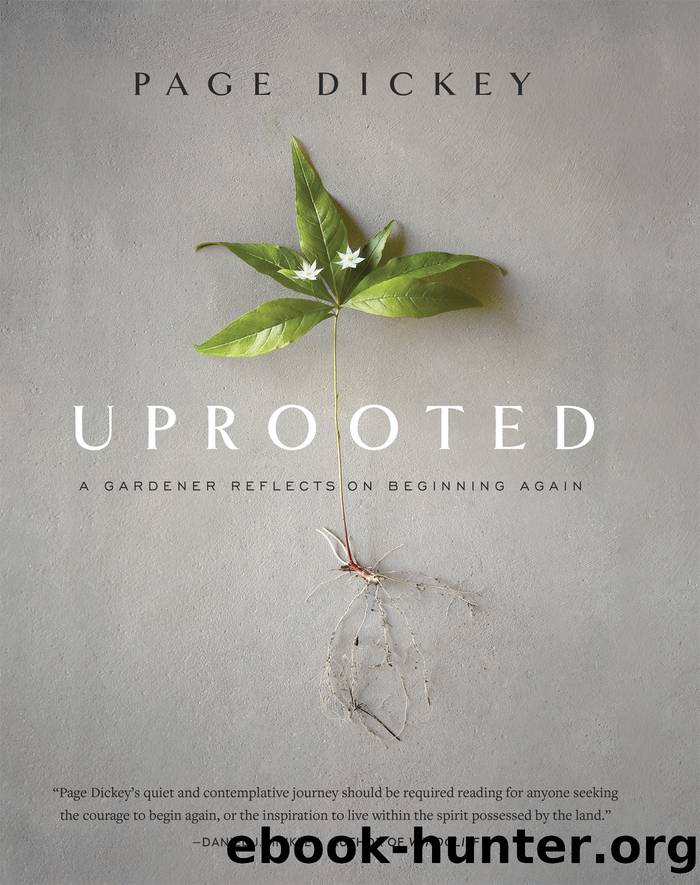

Uprooted: A Gardener Reflects On Beginning Again by Page Dickey

Author:Page Dickey

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Workman Publishing

Published: 2020-11-15T00:00:00+00:00

The old bank barn at Church House

From the bank front of the barn, we have a rough track to the road through a swath of high grass, on the south side abutting our neighborâs lawn. When we first moved in, I thought how romantic it might be to have a hedgerow of lilacs here as a screen, knowing these super-hardy shrubs would thrive in the full sun and our alkaline soil. We already have two lilac bushes (cultivars of Syringa vulgaris) at the front corners of the house, one a deep maroon, another white-floweringâI suspect, both planted by Nancy McCabe. An old raggedy stand near the garage of the ordinary lavender doubtless predates her. You would think that would be enough really, three different colors. But I was nonetheless tempted to collect other selections and colors, double white, pink, blue, and ink-purple, as well as one of the early flowering S. hyacinthiflora and a variety of the late S. prestoniae to extend the brief period of flowering. A hedgerow in full sun seemed ideal.

But the more I thought this spring about having a whole border of lilacs, as luscious as it would be in flower, the more it weighed on me that I would be planting in multiples a shrub that, like the beauty bush, had little to offer after its few days of bloom. The foliage inevitably gets mildewed, the shrubs themselves, unless of a venerable age, are rather gangly, and no autumn color or fruit redeems them. And nothing to attract bees or butterflies or birds. Surely I could plant something with more to offer, a plant that would enrich our wild habitat?

Iâve now decided as a compromise to include stretches of our native nannyberry, Viburnum lentago, in this screen of shrubs, along with some lilacs. Nannyberry grows 8 to 15 feet in height with a wide spread, has beautifully ribbed, lustrous leaves, arranged, as with all viburnums, in opposite pairs on reddish brown twigs, and has good red fall color. The cymes of small cream flowers in May are followed by edible blue-black fruit that ought to attract birds. It is also called sheepberry, possibly because âthe ripe and rotting fruit smell like wet sheep wool,â according to the University of Connecticut College of Agriculture. Iâm not altogether sure what wet sheep smells like.

I am unlikely to ever give up lilacs any more than Iâll forgo peonies or daffodils. Our common lilac is so indelibly associated with old farmhouses in New England and northern New York, you would think it a native. But, in fact, it is native to southeastern Europe, and was brought here by the earliest settlers to the colonies. The lilac specialist, Father Fiala, wrote in his seminal 1988 book, Lilacs: The Genus Syringa, that the oldest living specimens, dating from the 1750s, still thrived on Mackinac Island in Michigan (first brought there by the Hubbard family from New Hampshire who came to the island to farm), and in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, âmassive old trees, gnarled and twisted with the centuries.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3023)

Unfinished: A Memoir by Priyanka Chopra Jonas(2911)

Never by Ken Follett(2869)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(2289)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(2263)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(2058)

Will by Will Smith(2032)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(1760)

The Storyteller by Dave Grohl(1656)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1564)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(1562)

The Stranger in the Lifeboat by Mitch Albom(1527)

Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr(1428)

The Becoming by Nora Roberts(1323)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(1321)

Crying in H Mart by Michelle Zauner(1312)

Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson(1311)

New Morning Mercies: A Daily Gospel Devotional by Paul David Tripp(1299)

A Short History of War by Jeremy Black(1295)