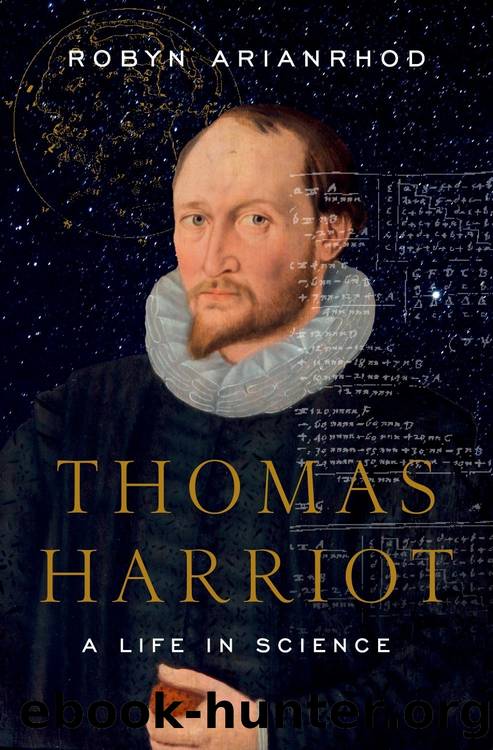

Thomas Harriot: A Life in Science by Robyn Arianrhod

Author:Robyn Arianrhod [Arianrhod, Robyn]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Biography & Autobiography, Science & Technology, history, Europe, Great Britain, General, Mathematics, History & Philosophy, science

ISBN: 9780190271855

Google: kjXcuQEACAAJ

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Published: 2019-11-15T00:31:03.443551+00:00

chapter 18

Atomic Speculations

Harriotâs theory of refraction involved a theory about matter itself, which he had tried out in his letter to Kepler. He was doing the same with his friend Torporley: it was during this period that Torporley wrote his notes of their discussions on the controversial subject of atomism.1

Torporley had the highest respect for Harriot as a mathematician and an experimentalist. In his 1602 book Diclides coelometricae, published not long after Harriot had discovered the law of refraction and while he was working on the trigonometry of the spherical triangle, Torporley had publicly praised him for dissipating, âby the splendor of undoubted truth, the philosophical clouds in which the world had been enveloped for many centuries.â2 But Diclides coelometricae is a rather odd book. It is on the topic of spherical trigonometry and combines obscure rhetoric, original theorems, and bizarre mnemonics. Unlike Harriot, Torporley did not shrink from publishing his work, no matter how slight. He seemed to have in mind astrologers rather than mathematicians as his readers. Astrology requires calculating angles between planets on the celestial sphere, and Torporley used astrological and other metaphors as mnemonic verses for remembering the required relationships between angles and distances in a spherical triangle. In view of Harriotâs work for Ralegh, perhaps Torporley had sailors in mind, too. Spherical triangles are needed to work out distances traveled along great circles, as Nunesâs work had also shown.

Torporleyâs admiration of Harriot dimmed somewhat over the yearsânot because of Harriotâs mathematics, which Toporley would continue to praise highly, but because of his freethinking. In particular, Harriotâs use of âatomsâ to explain refraction was âanathemaâ to Torporleyâs religious sensibility, and he was piqued that his friend was ârevivingâ such a âpseudo-philosophy,â as he put it.3 As we saw in connection with Harriotâs embroilment in the Cerne Abbas investigation back in 1594, the ancient idea that everything was created from pre-existing atoms suggested the heretical converse concept ex nihilo nihil fit: from nothing, nothing comes. For Torporley, such a concept was a denial of the biblical account in which God created the world from nothingâand he felt he needed to look no further than Aristotle for support. The ancient Greek philosopher might have believed in the eternity of the world, but he was acceptable to the Christian mainstream not only on account of his geocentric crystalline heavenly spheres but also because he had argued against the existence of discrete, indivisible atoms as proposed by Leucippus and his student Democritus in the fifth century bce. (The Greek atomos means âindivisible.â)4

Aristotle argued on such grounds as continuity. Time and space are surely decomposed into smaller and smaller parts, ad infinitum, he said; otherwise there would be gaps in space and time. These gaps would lead to paradoxes, such as Zenoâs âArrow.â (Zenoâs famous paradoxes have survived largely through Aristotleâs discussion of them.) If space and time were made of tiny discrete unitsâatoms of space, moments of time, which cannot be further subdividedâthen consider a moving arrow. If you take a snapshot at each separate moment, the arrow is at rest.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3051)

Unfinished: A Memoir by Priyanka Chopra Jonas(2918)

Never by Ken Follett(2887)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(2301)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(2295)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(2073)

Will by Will Smith(2045)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(1768)

The Storyteller by Dave Grohl(1662)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1571)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(1571)

The Stranger in the Lifeboat by Mitch Albom(1533)

Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr(1440)

New Morning Mercies: A Daily Gospel Devotional by Paul David Tripp(1337)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(1335)

The Becoming by Nora Roberts(1332)

Crying in H Mart by Michelle Zauner(1317)

Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson(1315)

A Short History of War by Jeremy Black(1300)