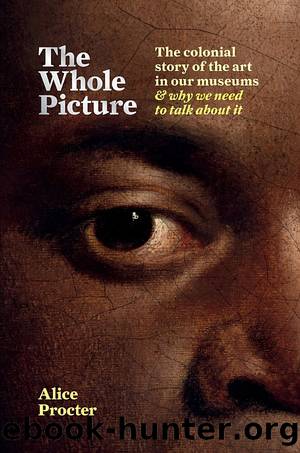

The Whole Picture: The Colonial Story of the Art in Our Museums & Why We Need to Talk About It by Alice Procter

Author:Alice Procter [Procter, Alice]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781788402217

Google: tsGtDwAAQBAJ

Published: 2020-03-19T00:00:00+00:00

The trusteesâ argument was that the museum could only deaccession the mokomokai if they were definitely preserved as part of commemoration, but since it was unclear which iwi these people had belonged to, or how the remains had been acquired, there was a chance they had been preserved specifically for sale to European collectors. Without further records, the mokomokai would stay by default. It is a cruel argument: the mokomokai have not been â and cannot be â displayed in the museum, and to treat them with respect any access should be limited. There has been no overt sign of the mokomokai being used as âsources of informationâ since the judgement was made; that is to say that, if research is ongoing, it has not been published. The statement showed unmistakeably a museum unwilling to move away from its self-image as all-knowing and all-controlling.

I started with a photograph you could not see, though its existence, its availability online, is a constant reminder of the cruelty of these collections. To keep holding ancestral remains, especially when those remains have been requested for repatriation and could be kept in a more appropriate place, is an act of violence. In the end it does not matter why these mokomokai were made, or if they were ever intended to be part of a funeral ceremony. The violence here is in the acquisition, and the keeping. The trade in ancestral remains originated in Europe â its history is not exclusively MÄori, though MÄori people participated in it. Even Robley managed to recognize that the trade which created his personal obsession was one that simultaneously contributed to a decline in the art of tÄ moko, as to be tattooed now came with such a high risk. The remains were always taken in a context of spectacle, treated as alluring grotesques, not as a âsource of informationâ. And museums have a part in this: the images produced, distributed and displayed by men like Sydney Parkinson, Joseph Banks and Horatio Robley made people into objects, emphasizing their appearance over their humanity and individuality. It was an inevitable progression from presenting those images to seeking the bodies themselves for show. Whatever the excuse or justification, for an institution to cling on to the ancestral remains in their collections today sends a clear message of valuing the body over the person. This is about more than the mokomokai in the British Museum; it is about how we relate to people and their remains, how institutions were complicit in the dehumanization of colonized and racialized communities. It is about trying to find a way to work against that. A museum is not a resting place; we cannot allow it to stay a graveyard.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Papillon by Henry Charrière(796)

Watercolor With Me in the Forest by Dana Fox(590)

The Story of the Scrolls by The Story of the Scrolls; the M(556)

This Is Modern Art by Kevin Coval(459)

A Theory of Narrative Drawing by Simon Grennan(456)

Frida Kahlo by Frida Kahlo & Hayden Herrera(445)

Boris Johnson by Tom Bower(443)

Banksy by Will Ellsworth-Jones(435)

AP Art History by John B. Nici(429)

Van Gogh by Gregory White Smith(426)

Draw More Furries by Jared Hodges(423)

The Art and Science of Drawing by Brent Eviston(423)

Glittering Images: A Journey Through Art From Egypt to Star Wars by Camille Paglia(420)

War Paint by Woodhead Lindy(414)

Scenes From a Revolution by Mark Harris(413)

100 Greatest Country Artists by Hal Leonard Corp(392)

Ecstasy by Eisner.;(386)

Young Rembrandt: A Biography by Onno Blom(374)

Theater by Rene Girard(355)