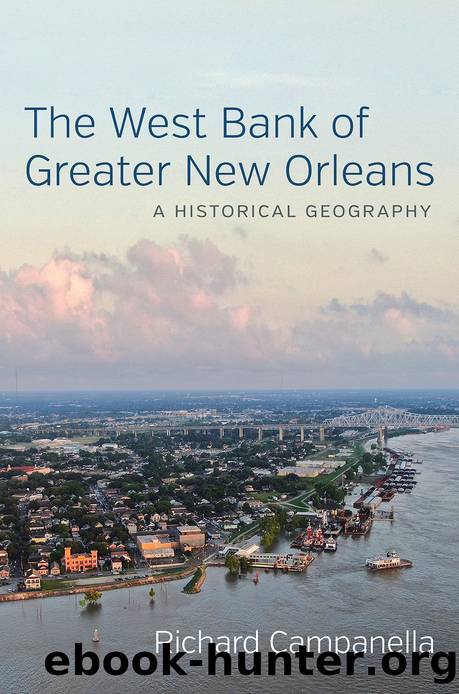

The West Bank of Greater New Orleans by Richard Campanella

Author:Richard Campanella

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: LSU Press

Published: 2020-06-14T16:00:00+00:00

As West Bank development sprawled southward and westward, new residents found themselves increasingly distanced from the very transportation arteries that got them there. The first houses of Terrytown, for example, sat only a thousand feet from the Mississippi River Bridge toll plaza, whereas the latest subdivisions in Algiers, Gretna, Harvey, and Marrero lay three to five miles away. Avondale Shipyards, largest employer in the region, was even farther west. As it became clear that commuting on the West Bank was becoming more onerous than commuting from the West Bank, stakeholders contemplated solutions. No one called for less development, nor greater housing density, but rather for additional bridges and expressways.

In 1964 the Jefferson Council presented plans from an engineering firm owned by David de Laureal and Warren G. Moses to build an Interstate 29 splitting off from the earlier 1946 plan of Robert Moses (no relation) for an expressway to points east, which by the 1960s was coming into fruition as Interstate-10. The I-29 spur of I-10 would form part of the New Orleans Outer Belt (or “Outer Loop”) that would run southward along Paris Road, cross a new river bridge from Chalmette to lower Algiers, run parallel to the recently completed Algiers (Intracoastal) Canal, continue westward along the Louisiana Power and Light Company (LaPaLCo) transmission right-of-way south of Lapalco Boulevard, and recross the river at another new bridge from Luling to Destrehan. The West Bank portion of the beltway was dubbed the “Dixie Freeway,” and the reason why it swung fully three miles south of the just-completed West Bank Expressway was to “open up more undeveloped land . . . south of the Timberlane Country Club and Terrytown.”21 In an article subtitled “Parish Prepares for Interurbia,” the Jefferson Parish Yearly Review announced in December 1968 that Congressman Hale Boggs had won federal approval for the Outer Belt. The term “interurbia,” not often used, perfectly describes the modern West Bank that was coming into form: the region had spots that were genuinely urban, surrounded by suburbia, yet it still had spots that were subrural, and all three land covers meshed together as interurbia.22

As contractors built I-10 and authorities pursued the $200 million needed for the Outer Belt, traffic increasingly overwhelmed the 1958 Mississippi River Bridge. Booming suburbanization had driven daily crossings to thirty-five thousand vehicles, which rocketed to fifty-two thousand per day when tolls were lifted in May 1964, in fulfillment of a campaign promise by Gov. John McKeithen. Funds would instead come from “a pledge of annual State stipends as security and support for the revenue bonds.”23 By the late 1960s, daily usage began exceeding the design capacity of sixty to sixty-five thousand per day, making commuters “fight a daily ‘battle of the bridge.’”24 It would only increase as the West Bank’s total population swelled from under one hundred thousand in 1960 to over one hundred seventy thousand in 1970, and as oil and gas investment grew throughout the coastal region.25

The Mississippi River Bridge Authority responded by broaching a third

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(10524)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(7557)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(4202)

Paper Towns by Green John(4171)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3803)

Be in a Treehouse by Pete Nelson(3216)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3051)

Goodbye Paradise(2966)

Never by Ken Follett(2887)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(2704)

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro(2621)

The Genius of Japanese Carpentry by Azby Brown(2610)

The Cellar by Natasha Preston(2596)

Drawing Shortcuts: Developing Quick Drawing Skills Using Today's Technology by Leggitt Jim(2532)

120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade(2441)

Architecture 101 by Nicole Bridge(2353)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(2301)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(2295)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(2073)