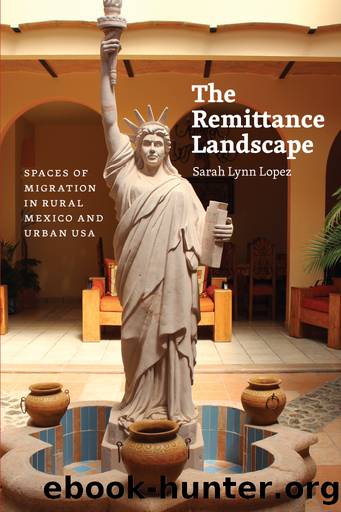

The Remittance Landscape by Sarah Lynn Lopez;

Author:Sarah Lynn Lopez; [Lopez, Sarah Lynn]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780226202952

Publisher: University of Chicago Press

Published: 2014-12-17T16:00:00+00:00

The Rise and Logic of the Traslado

Trasladosâthe âremittingâ of cadavers over long distances for burial in the home countryâare on the rise between the United States and Mexico. Being buried in oneâs hometown is a small measure of certitude, a dignified final act bringing closure to a life of uncertainty. The return to oneâs hometown (although after death) finally allows migrants to resolve an ambivalence central to a life of transnational migration: the perennial question of where one belongs. Burials in hometowns allow migrant families to participate in interment rituals that reinforce their position in the hometown despite their physical and temporal distance from it. They also reveal that the hometown is the place with which many migrants ultimately identify, and where they believe a community will remember them.

Today traslados are increasingly common, even for migrants of little means. Françoise Lestage, who conducted a study of traslados in 2008, estimates that one out of every six Mexican migrants who dies in the United States is buried in Mexico. Mexicoâs SecretarÃa de Relaciones Exteriores (Ministry of Foreign Relations) reports an average of thirty deceased Mexican migrants ârepatriatedâ from the United States daily.16 Customs service agents in the Guadalajara International Airport (where the bodies are subject to inspection) estimate that between thirty and fifty bodies are shipped to Guadalajaraâs airport each month.17 These bodies are then distributed throughout the region; families in Zacatecas, Michoacán, and Nayarit all collect their dead from Guadalajaraâs airport. This flow of the deceased requires the cooperation and logistical support of funeral homes and mortuaries on both sides of the border. Carolina DÃaz, who works in Funeraria Latino Americana in Los Angeles, which she believes is one of Californiaâs first and largest migrant-owned funeral homes, established in 1970, estimates that it ships between nine hundred and one thousand bodies to Mexico and Central America annually, five hundred of them destined for somewhere in Mexico. When I spoke to her in 2008, she said that âthe number of bodies has increased in the last five years because the number of Latinos living in the US has increased. The big increase started about five years ago.â18

According to funeral directors and migrants in both Jalisco and California, a gradual increase in traslados has occurred since the 1970s as the necessary money, technology, and social networks have become widely available to migrants and their communities. This increase demonstrates a fundamental shift in the logic of migration. By addressing a problematic aspect of migration as a way of lifeâuncertainty over the loss of loved onesâtraslados alleviate migrant suffering. Yet at the same time traslados are normalized and made more pervasive. For most migrants, the opportunity to finance a transnational burial is a great improvement compared even with the recent past. In the 1950s, Armando Juárezâs father, a bracero working in Texas, passed away. âBack then, it took a month to send a letter, if they ever got it. We couldnât imagine sending the body home.â19 Juárez believes that his father was murdered and is buried in Yuma, Arizona, or âsomewhere close by,â but he has never been to visit his grave.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(10520)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(7551)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(4198)

Paper Towns by Green John(4169)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3802)

Be in a Treehouse by Pete Nelson(3212)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3046)

Goodbye Paradise(2963)

Never by Ken Follett(2880)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(2701)

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro(2618)

The Genius of Japanese Carpentry by Azby Brown(2609)

The Cellar by Natasha Preston(2595)

Drawing Shortcuts: Developing Quick Drawing Skills Using Today's Technology by Leggitt Jim(2532)

120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade(2438)

Architecture 101 by Nicole Bridge(2350)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(2299)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(2291)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(2070)