The Fate of the Land Ko nga Akinga a nga Rangatira by Danny Keenan

Author:Danny Keenan

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Massey University Press

Published: 2023-08-15T00:00:00+00:00

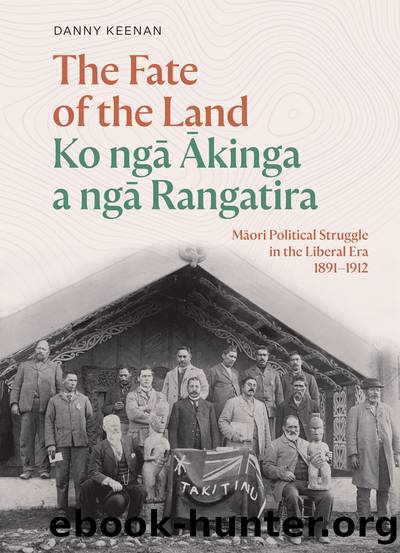

HÅne Heke NgÄpua, c.1893. Incisive and resolute, NgÄpua represented Northern MÄori in Parliament from 1893â1909. Gaining the support of Te Kotahitanga, he introduced his Native Rights Bill in 1894, calling on the PÄkehÄ government to grant political independence to Te Kotahitanga. ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY, 35MM-00188-A-F

On 28 September 1894, two weeks after NgÄpuaâs bill had lapsed in the House for want of a quorum, Seddon introduced the consolidating Native Land Court Bill, which aimed to clarify and streamline the courtâs processes, offering greater security of titles. As recently stated in the Supreme Court, he said, it was âalmost impossible to understand the existing lawâ.

Seddon reminded the House, and PÄkehÄ electors, of his resolve to âbring about friendly relationsâ with MÄori, thereby doing âjustice to our Native brethrenâ. MÄori had been losing confidence in the government, but if Parliament performed its tasks well, âthen I say we have for the last time heard of discord between PÄkehÄ and MÄoriâ. Seddon spoke at some length about his recent tour, which had been needed because âthe Native mindâ could not be ascertained âby remaining in Wellingtonâ. He had discerned that NgÄti Maniapoto were not the same as NgÄti Kahungunu, nor NgÄti WhÄtua, nor TÅ«hoe. Throughout the KÄ«ngitanga region, MÄori favoured individual dealing with land. But the rates of land loss were very high, especially following the confiscations, a matter that must be addressed by the House. MÄori in the Far North were âentirely opposed to dealing with the Governmentâ; they wished to establish their own parliament and govern themselves. East Coast MÄori favoured âtrusts being established and dealing by committees with the Government as corporate bodiesâ. He had âvery firmlyâ told TÅ«hoe that the surveys they were resisting were not intended to be detailed and they had been âquite prepared to agree to thatâ.21

Not surprisingly, James Carroll supported Seddon during the Native Land Court Bill debate. Although âa perfect Bill to meet all details and all conditions satisfactorilyâ was not possible, this legislation would ameliorate the restrictions and limitations in the law concerning MÄori land dealings, which were problematical for both MÄori and PÄkeha. The cost of individualising MÄori blocks âwould be an impossibility and in most instances would prove ruinous to the ownersâ. Carroll therefore supported the billâs proposed provision for tribal committees or corporate bodies. He concluded by speaking of landless MÄori in the King Country, who had âasked for land to be given to them so that they might settle upon itâ. There were other MÄori in Waikato, however, âvery well advanced in education, who [were] in daily communication with Europeans, who own land individuallyâ. They had prospered by separating themselves from the King Movement âbecause it was to their advantage to do soâ.22

The 134-section Native Land Court Bill became law on 23 October. Just a few days before, on the 18th, the Lands Improvement and Native Lands Acquisition Act was also passed. Its aim was âto make better provision for the preparation of lands for settlement and the acquisition of native landsâ.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Memory Code by Lynne Kelly(2397)

Schindler's Ark by Thomas Keneally(1879)

Kings Cross by Louis Nowra(1794)

Burke and Wills: The triumph and tragedy of Australia's most famous explorers by Peter Fitzsimons(1423)

The Falklands War by Martin Middlebrook(1381)

1914 by Paul Ham(1342)

Code Breakers by Craig Collie(1248)

A Farewell to Ice: A Report from the Arctic by Peter Wadhams(1245)

Paradise in Chains by Diana Preston(1244)

Burke and Wills by Peter FitzSimons(1234)

Watkin Tench's 1788 by Flannery Tim; Tench Watkin;(1228)

The Secret Cold War by John Blaxland(1210)

The Protest Years by John Blaxland(1202)

THE LUMINARIES by Eleanor Catton(1187)

30 Days in Sydney by Peter Carey(1157)

Lucky 666 by Bob Drury & Tom Clavin(1150)

The Lucky Country by Donald Horne(1138)

The Land Before Avocado by Richard Glover(1115)

Not Just Black and White by Lesley Williams(1082)