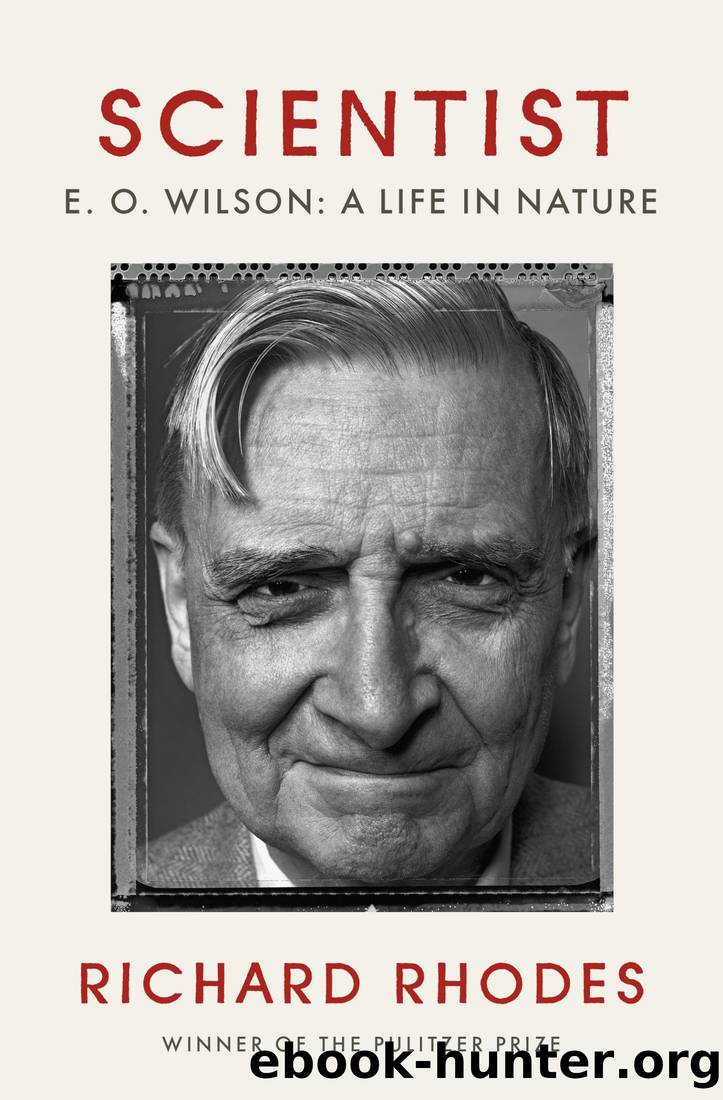

Scientist by Richard Rhodes

Author:Richard Rhodes [Rhodes, Richard]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Published: 2021-11-09T00:00:00+00:00

Altmann had warned Wilson to move carefully around the macaque infants or risk attack. If youâre challenged, Altmann cautioned, donât stare at the challenger; like most wild animals, macaques interpreted a stare as a threat. Bow your head and look away. Wilson needed the advice. On the second day of his visit, he moved too quickly near a young monkey, which shrieked its distress. âAt once the number two male ran up to me,â Wilson recalls, âand gave me a hard stare, with his mouth gapingâthe rhesus elevated-threat expression. I froze, genuinely afraid. Before Cayo Santiago I had thought of macaques as harmless little monkeys. This individual, with his tensed, massive body rearing up before me, looked for the moment like a small gorilla.â Wilson lowered his head and looked away. Eventually, the macaque accepted the gesture of submission and moved off.

Back on mainland Puerto Rico in the eveningsâCayo Santiago is less than a mile offshoreâWilson and Altmann discussed the social behaviors they studied, looking for connections. To Wilsonâs frustration, they found very few: âPrimate troops and social insect colonies seemed to have almost nothing in common.â Macaques were organized in dominance orders, each individual known and recognized. Social insects, anonymous and short-lived, flourished in caste-based harmony. In 1956, neither Wilson nor Altmann had the conceptual tools to map out much more than superficial connections, if any. Altmann got busy working on his doctoral dissertation on the Cayo Santiago macaques; Wilson returned to teaching and fighting off the molecular biologists.

Ironically, it was partly Wilsonâs struggle with the molecular biologists that led him to the approach to a unifying theory that he was looking for. That ongoing challenge had threatened to engulf evolutionary biology and continued to model a more formal and mathematical science. Wilson had titled the final chapter of The Insect Societies âThe Prospect for a Unified Sociobiology.â Though the term âsociobiologyâ had been used in other contexts as far back as 1912, Wilson appropriated it as a term of art meaning âthe systematic study of the biological basis of all social behavior.â Sociobiology, he thought, would grow out of population biology as a counterweight to molecular biology, because not everything in biology could be reduced to the molecular level. He had come to believe that âpopulations follow at least some laws different from those operating at the molecular level, laws that cannot be constructed by any logical progression upward from molecular biology.â

To that end, he studied population biology in the late 1960s even as he worked out the observational and theoretical scientific record of the social insects. Not one to waste such an effort, he and his Harvard colleague William H. Bossert, a biologist and applied mathematician, wrote A Primer of Population Biology, publishing the densely mathematical book the same year as The Insect Societies, 1971.

If none of his colleagues who were vertebrate specialists were prepared to write about the social behavior of the vertebrates, he would have to do that work himself: he was, as he says, a âcongenital synthesizer.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(10520)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(7551)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(4198)

Paper Towns by Green John(4169)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3802)

Be in a Treehouse by Pete Nelson(3212)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3045)

Goodbye Paradise(2963)

Never by Ken Follett(2880)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(2701)

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro(2618)

The Genius of Japanese Carpentry by Azby Brown(2609)

The Cellar by Natasha Preston(2595)

Drawing Shortcuts: Developing Quick Drawing Skills Using Today's Technology by Leggitt Jim(2532)

120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade(2438)

Architecture 101 by Nicole Bridge(2350)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(2299)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(2291)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(2070)