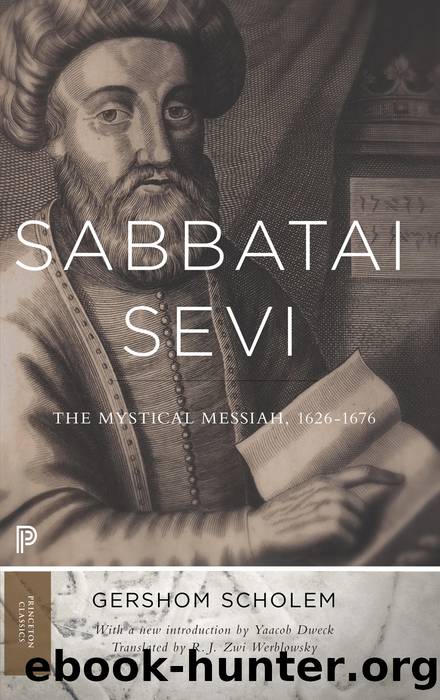

Sabbatai Ṣevi by Scholem Gershom; Dweck Yaacob; Werblowsky R. J. Zwi

Author:Scholem, Gershom; Dweck, Yaacob; Werblowsky, R. J. Zwi

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Princeton University Press

Published: 2016-08-14T16:00:00+00:00

II ITALY

The reports arriving first from Egypt, then from Smyrna and the Balkans, caused profound agitation in Italy. The kind of news that reached Italy is illustrated by the summary made by Emanuel Frances22 as well as by copies of, and quotations from, letters and news reports that have been preserved. Copies of the news reports from the East circulated in all congregations, and it was not long before the first reactions manifested themselves. The movement did not begin at the bottom, among the lower classes, for we find a goodly number of rabbis and lay leaders heading the revival. In the greater communities, such as Leghorn, Venice, Florence, Ancona, Mantua, and Casale, the majority of the scholars were believers, and as the most prominent feature of the messianic tidings was the call to repentance, even the more cautious and hesitant rabbis—and there were many of them, particularly in Venice—could not but support a movement that promised a religious revival and a reformation of morals. Nathan’s manuals of devotions, of which two editions appeared in Mantua,23 were appointed to be used in the synagogues. The aloofness of the printing houses in Venice is surprising.24 They may have refrained so as not to irritate the government of the republic, or—more probably—because the “Scholars of the Great Academy,” who were also the rabbinic licensing authority for the printing of Jewish books, could not agree on the matter.

Italian Jewry had been profoundly affected by the kabbalistic movement of the preceding century. Italy had been the first European country to be reached by the kabbalistic propaganda emanating from Safed in the sixteenth century, and in many communities brotherhoods were formed for the purpose of practicing special ascetic and liturgical devotions. These brotherhoods played an important role in the life of the Jewish communities in the period preceding the messianic stir, and their copious liturgical literature bears witness to the profound influence of the new kabbalah.25 The messianic tidings appeared as a continuation of the original, more pietistic revival. The leading exponents of Palestinian kabbalism, R. Benjamin ha-Levi of Safed and Jerusalem, and R. Nathan Shapira of Jerusalem, had spent much time in Italy. The former did not return to Palestine until 1660–63, and the latter died in Reggio in the spring of 1664,26 about two years before the messianic awakening. Both had exerted great influence, through their many friends and disciples, on the religious life of the more kabbalistically minded. R. Benjamin ha-Levi supported the movement from Palestine, and wrote to his Mantuan friends, members of the patrician Norsa and Sullam families, about “our redemption by our king Sabbatai Ṣevi.”27 R. Nathan Shapira had preached before his death a series of what may perhaps be described as “proto-Sabbatian” sermons, since Mortara, who had examined a manuscript of these homilies, concluded from them that their author “shared the fantastic illusions of some of his contemporaries regarding the imminent advent of redemption.”28

In Siena newborn children were being given the name Sabbatai as early as December, 1665,

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Haggadah | Hasidism |

| History | Holidays |

| Jewish Life | Kabbalah & Mysticism |

| Law | Movements |

| Prayerbooks | Sacred Writings |

| Sermons | Theology |

| Women & Judaism |

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. Frankl(2254)

The Secret Power of Speaking God's Word by Joyce Meyer(2253)

Mckeown, Greg - Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less by Mckeown Greg(2112)

MOSES THE EGYPTIAN by Jan Assmann(1972)

Unbound by Arlene Stein(1940)

Devil, The by Almond Philip C(1899)

The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English (7th Edition) (Penguin Classics) by Geza Vermes(1840)

I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith(1571)

Schindler's Ark by Thomas Keneally(1514)

The Invisible Wall by Harry Bernstein(1458)

The Gnostic Gospel of St. Thomas by Tau Malachi(1412)

The Bible Doesn't Say That by Dr. Joel M. Hoffman(1372)

The Secret Doctrine of the Kabbalah by Leonora Leet(1267)

The Jewish State by Theodor Herzl(1251)

The Book of Separation by Tova Mirvis(1224)

A History of the Jews by Max I. Dimont(1206)

The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible by Martin G. Abegg(1200)

Political Theology by Carl Schmitt(1187)

Oy!: The Ultimate Book of Jewish Jokes by David Minkoff(1104)