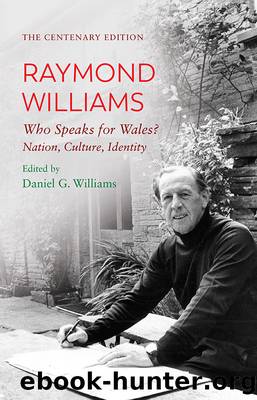

Raymond Williams: Who Speaks for Wales? Nation, Culture, Identity. The Centenary Edition by Daniel G. Williams

Author:Daniel G. Williams [Williams, Daniel G.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781786837066

Google: tPWbzQEACAAJ

Publisher: University of Wales Press

Published: 2021-05-15T23:28:33.175449+00:00

Footnotes

a Raymond Williams, Border Country (London: Chatto & Windus), p. 240.

b Border Country, p. 351.

c Border Country, p. 288.

d Raymond Williams, Second Generation (London: Chatto & Windus), p. 318.

FREEDOM AND A LACK OF CONFIDENCE

Arcade, 12 (17 April 1981), 16â17.

There are no rules about the novel as a form. It has made them up as it has gone along. From collections of letters to impersonal narratives, from what look like private diaries to what read like tape-recordings of others, from past and present to a variety of futures, it has made its own ways.

But this doesnât mean there arenât effective traditions, in particular times and places. For a run of years and writers the novel can seem, temporarily, to be stable: all the deep choices made by the effective form, leaving writers to their particularities inside that.

This isnât really so anywhere now. A number of forms are internationally current: from thrillers to myth-making fantasies, from science fiction to accounts of enclosed personal relations â this last still claiming a unique authenticity. There are still what are called historical novels, meaning usually stories set in some particular period of the past rather than stories involving the movements of history. There are also still some social novels: presenting people in a crisis of their own place and time.

In this general and international diversity, it is not to be expected that the novel in Wales has any single operative direction or form. The effect, in Wales as elsewhere, is double-edged. It gives us freedom: we can do it our own ways. But this kind of freedom is often, in practice, a disabling lack of confidence. It is one of the paradoxes of artistic freedom that it often flourishes best when there is some deep agreement about purposes and methods.

Moreover, when you put that kind of negative freedom alongside market conditions in which there is more supply than effective demand, and in which novel-writing, in particular, with its long investment of time, can seem quixotic by comparison with journalism, broadcasting, short plays, essays, you are likely to get more than the usual amount of self-doubt, complaint, critical irritability, conspiracy theory and cynical resignation.

These attitudes are not exactly unknown in contemporary Wales, or among its writers in either language. There are some specific reasons, though for the most part the reasons are general and can be found, with much the same effects, almost everywhere. But take the specific reasons. There is a genuine problem between the two languages, exacerbated, in the case of the novel, by the fact that the prose fictional tradition is very much shorter in Welsh than in English.

There is also, nevertheless, the problem of past success, though we seem very reluctant to acknowledge this. From the 1920s, through to the 1940s there was an effective tradition of novels in English about the industrial crisis: Jack Jones, Gwyn Jones, Lewis Jones, Richard Llewellyn.1 Limited as this was, it is still remarkable in Europe as a form of writing largely by, about and for a conscious working class.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4295)

Never by Ken Follett(3937)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3848)

Unfinished: A Memoir by Priyanka Chopra Jonas(3381)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3370)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3072)

Will by Will Smith(2911)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2352)

It Starts With Us (It Ends with Us #2) by Colleen Hoover(2344)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(2324)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(2300)

The Storyteller by Dave Grohl(2229)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(2219)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(2197)

The Becoming by Nora Roberts(2189)

The Stranger in the Lifeboat by Mitch Albom(2113)

Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr(2101)

Love on the Brain by Ali Hazelwood(2062)

Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson(2011)