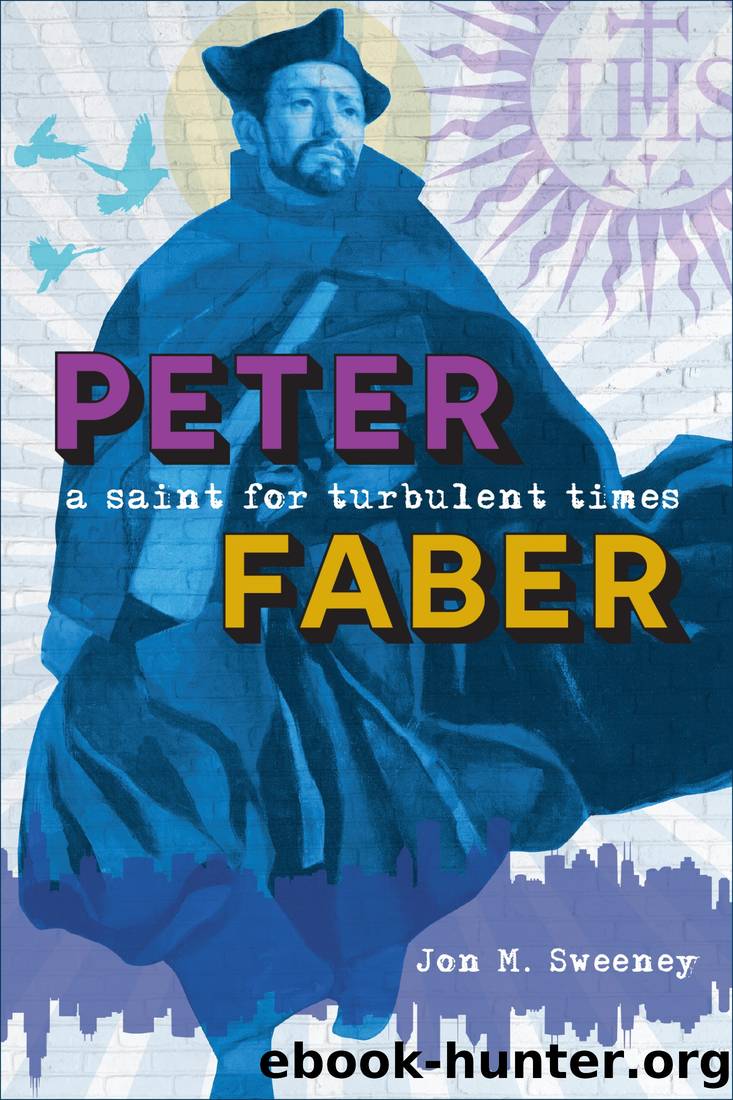

Peter Faber: A Saint for Turbulent Times by Jon Sweeney

Author:Jon Sweeney [Sweeney, Jon]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Catholic, Religion, BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Religious, Biography & Autobiography, BIO018000, Religious biography, Religious, Jesuit saints, Christian Historical theology, RELIGION / Christianity/Catholic, REL010000, Christianity

ISBN: 9780829445220

Google: Hxt9zQEACAAJ

Publisher: Loyola Press

Published: 2021-02-15T00:09:30.256522+00:00

Seeking Truth and Abandoning Cooperation

Most reformers, including Catholics, as well as the new Protestant churches, believed they were the âtrue churchâ and, correspondingly, that all others were untrue. Appeals to religious or theological purity were not new, of course; they went back centuries to early church controversies. And heretical movements were nothing new. Most of all, in the mountainous regions of Europe, ancient heresies were kept alive. In such places, those who held to dangerous opinionsâoften centering on views of Christ that diverged from the teachings of the church, or notions that the world we live in is unreal or controlled by evil forces, or practices of asceticism and notions of purity that were unnatural and not Christianâfelt safe from the reaches of Rome and empire.

Luther told his followers that reforming churches were the only âtrueâ ones. He called the Catholic Church a whore and declared that it was trapped in a new sort of âBabylonian Captivity,â having lost its way. John Calvin taught his followers something similar and set out to create a theocracy in Geneva that would enlist the state to help the church guide souls through their earthly sojourn and then safely to salvation and the afterlife. This was an era that knew nothing of the separation of church and state. On the contrary, each state was headed by a monarchy, and that monarchy believed its power derived directly from Godâas per various lines in the Bible used to confirm such a perspective.

One more detail: There was another common belief that added more kindling to these fires. Namely, human beings have a holy obligation to correct one another when they have lost their way in matters of religious truth. This can be traced back to Thomas Aquinas, who taught in his Summa Theologica that it was worse to lose oneâs earthly life than to die in apostasy and lose eternal life.70 Such an ideaâembraced by the churchâled logically to inquisitions. In Calvinâs theocratic Geneva, for instance, the reformer himself would infamously oversee a burning at the stake of at least one deemed heretic (Michael Servetus, in 1553). And a few years after that, the second-generation Jesuit Robert Bellarmine (now St. Robert Bellarmine) would argue that Catholics in a Catholic state were not only entitled to but also responsible for executing heretics if thatâs what it took to conform them to Catholic ways of belief and practice.

Every opposing side affirmed its right and obligation to defend itself against those groups and states they believed heretical and to aid those who agreed with them in such states to overthrow their government and even kill a monarch. Monarchs may receive their right to reign from God, but that right is voided when that monarch is not found within the âtrueâ church. This was when Christians did not believe that tolerance of religious differences was in their creed. Voltaire would write: âWe have Jews in Bordeaux, Metz and Alsace; we also have Lutherans, Molinists and Jansenists. Could we not tolerate and accommodate Calvinists .

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4314)

Never by Ken Follett(3960)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3864)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3401)

Unfinished: A Memoir by Priyanka Chopra Jonas(3393)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3082)

Will by Will Smith(2924)

It Starts With Us (It Ends with Us #2) by Colleen Hoover(2370)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2368)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(2344)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(2312)

The Storyteller by Dave Grohl(2240)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(2234)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(2213)

The Becoming by Nora Roberts(2207)

The Stranger in the Lifeboat by Mitch Albom(2127)

Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr(2116)

Love on the Brain by Ali Hazelwood(2080)

Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson(2028)