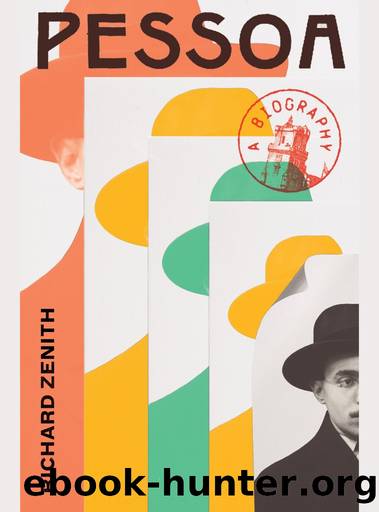

Pessoa: A Biography by Richard Zenith

Author:Richard Zenith [Zenith, Richard]

Language: eng

Format: azw3

Tags: Biography & Autobiography, Nonfiction, History

ISBN: 9780871404718

Publisher: Liveright

Published: 2021-07-12T23:00:00+00:00

CHAPTER 44

EVER SINCE THE PUBLICATION OF ORPHEU 1, WHOSE most talked-about contribution was Ãlvaro de Camposâs reputedly futurist âTriumphal Ode,â Pessoa had been distancing himself from Marinettiâs movement, but José de Almada Negreiros and Santa Rita Pintor were still fervent advocates of futurism. What attracted them, more than its artistic methods, was the audacious and arrogant, impolite figure of the futurist artist. It was a style, which they cultivated. On April 14, 1917, Almada Negreiros delivered a âFirst Futurist Lectureâ at the Theater of the Republic (now the São Luiz Theater). Appearing on stage in a jumpsuit of his own design, a kind of lightweight aviator suit, he warmly introduced Santa Rita Pintor, who would intermittently jump up from his seat in one of the boxes, fielding questions or responding to objections from people in the audience, who were allowed and even encouraged to interrupt the proceedings. In a stentorian voice Almada Negreiros recited three manifestos, including Portuguese translations of the âFuturist Manifesto of Lust,â published in 1913 by the writer and artist Valentine de Saint-Point, and Marinettiâs âThe Variety Theater,â also from 1913. Almada Negreiros began the session by reciting his own âFuturist Ultimatum to the Portuguese Generations of the Twentieth Centuryââa manifesto that denounced Portuguese decadence, challenged his generation (he had just turned twenty-four) to revitalize the nation, and praised the Great War for annihilating reactionary sentimentalism and awakening the spirit of creativity and construction.

If Pessoa attended the lecture, he must have cringed at his friendâs glorification of war, which went on at some length, echoing Marinettiâs contention that war was âhygienicâ as well as energizing. The Italian futurists, it must be said, not only supported the Great War with their words, by collaborating with the propaganda service of the army, they also fought in it as soldiers. Although Pessoa agreed with Heraclitus that war is the mother of all things,1 although he theoretically approved of Germanyâs ambitions to expand its empire through armed force, and although he had tried to market several war games of his own invention back in 1915, actual war horrified him, and the negotiated participation of Portuguese soldiers in the European war was to his mind unconscionable.

Even if the Portuguese negotiators acted in good faith, events quickly suggested that they had made a poor deal. Despite the British line of credit extended to Portugal like a float for a man drowning, the nationâs financesâstrained by the expense of outfitting and training the soldiers it sent to Franceâfloundered more than ever. Unable to import enough wheat, on May 10 the government decreed that all bread sold had to be baked with a certain percentage of corn flour. The loaves thus produced were deemed inedible by some, and many bakeries simply turned off their ovens. More affluent classes could purchase, at a premium, bread baked in surrounding towns or by private individuals, but the urban poor were increasingly malnourished. Food riots, collectively known as the Potato Revolt, broke out in and around Lisbon,* markets and

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4283)

Never by Ken Follett(3922)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3835)

Unfinished: A Memoir by Priyanka Chopra Jonas(3362)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3358)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3055)

Will by Will Smith(2891)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2344)

It Starts With Us (It Ends with Us #2) by Colleen Hoover(2319)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(2312)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(2290)

The Storyteller by Dave Grohl(2212)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(2208)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(2184)

The Becoming by Nora Roberts(2179)

The Stranger in the Lifeboat by Mitch Albom(2104)

Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr(2082)

Love on the Brain by Ali Hazelwood(2046)

Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson(1997)