Passionate Detachments by Amy Rust

Author:Amy Rust

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: State University of New York Press

Published: 2017-02-14T16:00:00+00:00

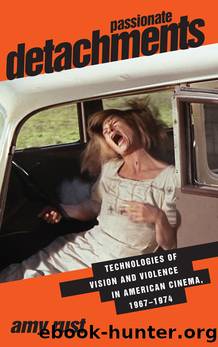

Figure 3.4. Rock music: one of the eraâs many rituals of authentication (Gimme Shelter, 1970).

Still, the rebellion that joined dominant to countercultureâthe latter increasingly and contradictorily mainstreamâalso exacerbated distinctions between the two spheres, particularly as ecstasy turned violent in the popular imaginary. It is the case, of course, that small segments of American youth did participate in acts of physical violence as the 1960s came to a close. Protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention and the Weather Undergroundâs 1969 Days of Rage were, like the Stones concert at Altamont, only the most prominent examples. It is also the case, however, that American media increasingly covered only the most violent youth actions, cleaving them from ânonviolentââthough certainly confrontationalâactivities such as marches, strikes, and sit-ins. âEven when events were virtually violence-free,â writes historian Melvin Small, âjournalists pointed that out at the beginning of their stories or in headlines, ⦠reinforcing the notion that demonstrations meant violenceâ andâI would addâthat nonviolent tactics somehow evaded coercion (162). Thus fracturing the youth movement, popular accounts gave prominence to its most immoderate factions, the participants of which answered the press in kind.

As a result, young people seemed to stand more and more outside the confines of conventional culture, consolidating fantasies of extremism among those who supported and opposed it. For one side, marginality promised authentic rebellion, or so people of color, especially African Americansâfrom Harlem hipsters to civil rights activists to Black Power militantsâappeared to attest. At odds with the âsilent majority,â young radicals believed themselves similarly subjugated. To respond to violence with violence was, therefore, to generate a repressive, and thereby revelatory, response. For the other side, violent provocations disclosed nothing, however, except perhaps a generation bent on apocalypticism for its own sake.

And yet, because each side saw only the otherâs self-serving brutality, they misrecognized the visions of violenceâpopular, apocalyptic, and articulated in othernessâthat, in fact, entwined them both. In particular, they missed the way in which people of colorâand African Americans in particularâdefined their cultural differences. According to Rossinow, urban riots between 1965 and 1968 âleft a deep imprint on many conservative Americans, driving them further to the political right. They associated violence,â he continues, âwith black Americans, not whitesâ (271). Leftist radicals made similar assumptions, though they admired rather than maligned the brutality in question. Notes former Weatherman Jeff Jones:

People like the Vietnamese and, in this country, people in the black community, especially people like the Black Panther Party, were in a state of revolutionary warfare. The question was: Were we going to join that war on terms equal to what black people or Vietnamese people were doing, or were we going to continue to use our privilege as white people as an excuse for not accepting the same level of risk? (311)

Here, overcoming alienation means emulating those whose lives are on the line. Doing so may challenge middle-class banality, but it also contributes to fantasies of violence as authentically âotherâ at the same time.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Japanese by Christopher Harding(1129)

Glittering Images: A Journey Through Art From Egypt to Star Wars by Camille Paglia(781)

Watercolor With Me in the Forest by Dana Fox(775)

A Theory of Narrative Drawing by Simon Grennan(767)

The Story of the Scrolls by The Story of the Scrolls; the M(752)

Boris Johnson by Tom Bower(643)

This Is Modern Art by Kevin Coval(624)

Frida Kahlo by Frida Kahlo & Hayden Herrera(607)

The Art and Science of Drawing by Brent Eviston(606)

AP Art History by John B. Nici(602)

Banksy by Will Ellsworth-Jones(586)

About Looking by John Berger(585)

Van Gogh by Gregory White Smith(575)

Scenes From a Revolution by Mark Harris(573)

War Paint by Woodhead Lindy(567)

Draw More Furries by Jared Hodges(561)

Ecstasy by Eisner.;(557)

100 Greatest Country Artists by Hal Leonard Corp(538)

Young Rembrandt: A Biography by Onno Blom(535)