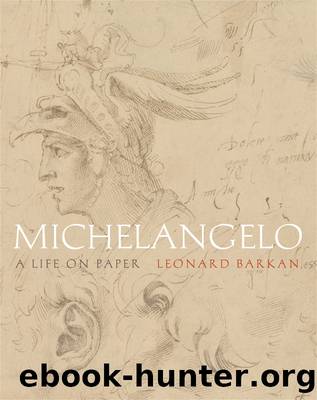

Michelangelo by Leonard Barkan

Author:Leonard Barkan

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Princeton University Press

Published: 2022-05-28T00:00:00+00:00

Never mind that this is all Petrarchan pastiche and not nearly Michelangeloâs best work in that vein. What we have on this page is a conjunction between the experience of a joyously crowded artistic and personal life and the ritual rejection of precisely that sense of fullness. Perhaps the sheet contained the poem and subsequently got passed through the serendipities of the studio; or perhaps the artistic labors of Master and pupils had already taken place when Michelangelo went back and covered a third of them with the completion of what is likely to have been a pre-existing rough draft from another sheetâsince, until the very end, there are no verbal corrections here. Either way, he is living out the paradox of an artistic and affective life among friends as opposed to a sense of obligation before his eternal judge; with that latter perspective in his mind, all this crowded company merely becomes a sign that not a single day has been his own.

But why should Michelangeloâs days have been his own? By the time he had reached the mezzo cammin of his unusually long life, he was the world-famous, highly sought after, and professionally over-committed boss, both artistic and managerial, of an enormous construction enterprise. Monumental church façades and papal tombs donât just build themselves; and it is noteworthy that Michelangelo, for all his famous problems with sociability, concentrated his career on every form of artistic production except the oneâpanel paintingsâthat his contemporaries tended to produce solo. However grave his concerns about standing before his Maker with nothing to show for himself but a lot of dedication to art and an insufficiency of God-fearing solitude, he had committed his life to work that required collaboration.

In effect, Michelangelo was becoming more than anything else a designer of architecture, though that term has to be construed broadly when applied to the present body of work. By the end of his career, with such enterprises as St. Peterâs, the church of S. Giovanni dei Fiorentini, and the Palazzo Farnese in the works, Michelangelo was exerting himself in projects that would fit anyoneâs definition of large-scale construction. In the earlier decades, we were confronted rather with sculpture that looked like architecture (e.g., projects for the Julius Tomb) or architecture that looked like sculpture (e.g., the Laurentian Library vestibule), or painting that looked like sculpture and architecture (the Sistine Ceiling). But whatever generic terminology is appropriate to these undertakings, nearly all involved communication among many collaborating individuals. Which meant inevitably that pieces of paper were being inscribedâand not only in order that the Master could brainstorm or that the studio could engage in some sociable pedagogy. Rather, sheets needed to pass from hand to hand for fundamental, practical purposes: for acquiring raw materials, for communicating artistic conceptions either to patrons or workers, and for directing the artisans at each work site. Moreover, all of this complex, interpersonal enterprise must endure the further pressures of geography, involving as it did contact among persons variously located in Florence, Rome, and the marble quarries of Northern Tuscany.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(10519)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(7551)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(4195)

Paper Towns by Green John(4169)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3800)

Be in a Treehouse by Pete Nelson(3212)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3045)

Goodbye Paradise(2962)

Never by Ken Follett(2880)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(2701)

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro(2618)

The Genius of Japanese Carpentry by Azby Brown(2609)

The Cellar by Natasha Preston(2595)

Drawing Shortcuts: Developing Quick Drawing Skills Using Today's Technology by Leggitt Jim(2532)

120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade(2437)

Architecture 101 by Nicole Bridge(2350)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(2298)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(2290)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(2069)