Louis Kahn by Carter Wiseman

Author:Carter Wiseman [Wiseman, Carter]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: ARC005000 Architecture / History / General

Publisher: University of Virginia Press

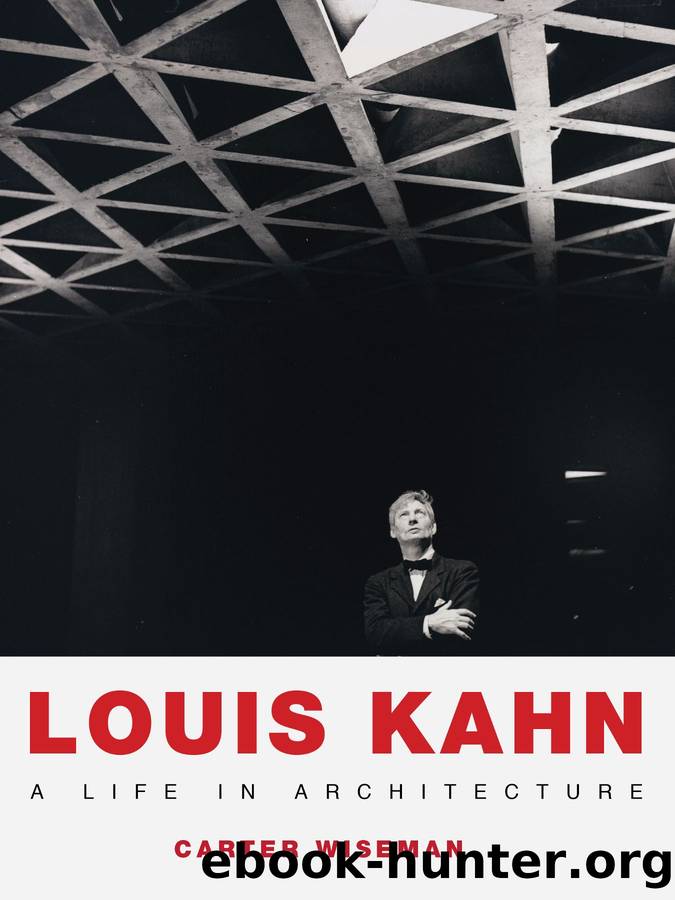

FIGURE 24. For some critics, the completed Richards building evoked historical precedents that suggested a path beyond modernism. (©Richard Lautman Photography, National Building Museum)

When it opened, in 1961, Richards was a critical sensation, covered in more than two hundred publications in the United States and abroad, and the subject of a one-building show at New Yorkâs Museum of Modern Art. One writer later declared that, âIn its functionalism, response to program, honesty in use of materials, and use of glass, the building is a culmination of modern architecture. At the same time it transcends modern architecture and becomes something new.â5 Vincent Scully, regardless of his growing reservations about Kahnâs verbosity as a teacher, speculated that the architect had found a solution to one of modernismâs most serious shortcomings: its abandonment of architectural history. In his 1962 monograph, Scully described the Richards building as âreminiscent surely of San Gimignano and Siena.â6 On the surface, the connection made sense. Kahn had visited both Italian hill towns during his stay at the American Academy in Rome, and there is an undeniable visual similarity between the forms of the towers in Italy and Philadelphia. But Kahn vigorously dismissed the connection, insisting that Richards was an original conception generated by the program and the cramped site. Never one to concede artistic influence, he may have overstated his position. In any case, Scullyâs interpretation had a fundamental impact on American architects.

Ever since Ludwig Mies van der Rohe had finished his elegantly austere Seagram Building in New York City, architects such as Edward Durell Stone, Eero Saarinen, and Philip Johnson had been searching for ways to reintroduce visual and emotional appeal in architecture. The very suggestion that Kahn had drawn on medieval sources suddenly afforded permission to revisit historical precedents, something that had been proscribed by orthodox modernism.

One of the most ringing endorsements of Richards came from the architectural historian William Jordy. In a thorough analysis of its importance, he concluded that âKahnâs building is real in its tangibility; real in materials and structure; ostensibly, if not literally, real in the inevitability with which the composition unfolds from a functional conception; hence real in its scorn of superficial beauty. If âbeautifulâ at all, it is so as a dogmatic manifestation of character.â7

Not all the response to Richards was so positive. Reyner Banham, an English critic, was especially harsh; in withering prose, he pointed out the conflict between the buildingâs apparent message of structure and mass and its manipulation of form for visual effect.8 The most obvious example was the contrast between the fully enclosed mini-towers, which can be read as solid supports for the laboratory floors but actually contain exhaust ducts, and those towers that housed stairs but were open at the top, revealing their hollow-core construction and their very divergent function. In both cases, an architectural element appears to be doing one thing while in fact it is doing another, a fundamental betrayal of modernist doctrine that structure be expressed honestly. Banhamâs criticisms recalled the debate

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(10506)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(7542)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(4188)

Paper Towns by Green John(4163)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3789)

Be in a Treehouse by Pete Nelson(3206)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3024)

Goodbye Paradise(2949)

Never by Ken Follett(2872)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(2695)

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro(2614)

The Genius of Japanese Carpentry by Azby Brown(2602)

The Cellar by Natasha Preston(2592)

Drawing Shortcuts: Developing Quick Drawing Skills Using Today's Technology by Leggitt Jim(2527)

120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade(2428)

Architecture 101 by Nicole Bridge(2348)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(2289)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(2264)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(2058)