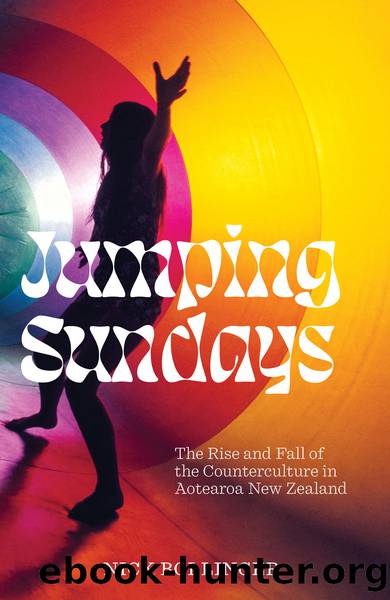

Jumping Sundays: the Rise and Fall of the Counterculture in Aotearoa New Zealand by Nick Bollinger

Author:Nick Bollinger

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Auckland University Press

Published: 2022-08-15T00:00:00+00:00

URBAN NETWORKS

Mixed flatting became increasingly common, particularly in the university towns. Sue Belt was eighteen when she moved into a flat in Thorndon with her musician boyfriend Peter Kennedy, his bandmates Rick Bryant and Julie Needham, and student politician-turned-music promoter Graeme Nesbitt. But, like many, she kept her living arrangements under wraps. âMum and Dad would come round and I never really told them I was living with boys. I remember they came upstairs to Peterâs and my room and I had to kick all his shoes under the bed, because even though Iâd said I believed in free love Iâd never quite admitted to them that we were living together.â4

Flatting didnât just make it feasible to sleep with your partner. Flats could be conscious experiments in communal living, making it possible for all the accepted conditions for the survival of the species â food, shelter, clothing, sex â to be reconsidered in ways that diverged from societal norms. It was possible for flatters to work in paid employment only for as much or as long as was necessary for survival, enabling the maximum amount of time to be reserved for the things that mattered most, whether creative, spiritual, political or recreational.

By the early seventies, Rachel Stace was living with thirteen others, whose shared interests included drugs, sex and music, in a rambling two-storey villa in Herne Bay, paisley scarves tied around hanging lamps, the back garden overgrown. An outhouse and adjoining cottage were included in a total rental of $36 per week. âWe could afford to spend $40 on acid at the weekend and still have enough left over for food.â5 Rachel worked as a postie, then as a clerk in the Department of Social Welfare, leaving each job once she had amassed enough money to pay her way for the next few months. Other members of the household took a similarly pragmatic, career-averse approach to employment. One or two were students living on bursaries.

Some flats were furnished by landlords, others by their tenants. Used chairs, couches, tables and other suburban cast-offs could be bought cheaply from second-hand shops, or were contributed by parents. Bed bases and bookcases were constructed from found materials such as pallets and bricks. Flats seldom had televisions. A single stereo would be set up in the main living area and used by all residents; collections of records and books were frequently pooled. The ethos was non-acquisitive and non-materialistic. As household members came and went, they would often leave items behind for the continued use of the household. âYou didnât accumulate things then,â recalled Nicholas Pounder. âYou left them on the floor or on the wall.â6

Brent Morrissey had grown up in Christchurch but gone to Australia as a teenager in search of adventure. In Sydney he took a job as a mail sorter, only to discover that young New Zealanders working for the Australian government could be conscripted and sent to Vietnam. When officials turned up at his flat one morning, he hid under the

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Memory Code by Lynne Kelly(2397)

Schindler's Ark by Thomas Keneally(1879)

Kings Cross by Louis Nowra(1794)

Burke and Wills: The triumph and tragedy of Australia's most famous explorers by Peter Fitzsimons(1423)

The Falklands War by Martin Middlebrook(1381)

1914 by Paul Ham(1342)

Code Breakers by Craig Collie(1248)

A Farewell to Ice: A Report from the Arctic by Peter Wadhams(1246)

Paradise in Chains by Diana Preston(1245)

Burke and Wills by Peter FitzSimons(1235)

Watkin Tench's 1788 by Flannery Tim; Tench Watkin;(1228)

The Secret Cold War by John Blaxland(1211)

The Protest Years by John Blaxland(1203)

THE LUMINARIES by Eleanor Catton(1187)

30 Days in Sydney by Peter Carey(1157)

Lucky 666 by Bob Drury & Tom Clavin(1150)

The Lucky Country by Donald Horne(1139)

The Land Before Avocado by Richard Glover(1116)

Not Just Black and White by Lesley Williams(1083)