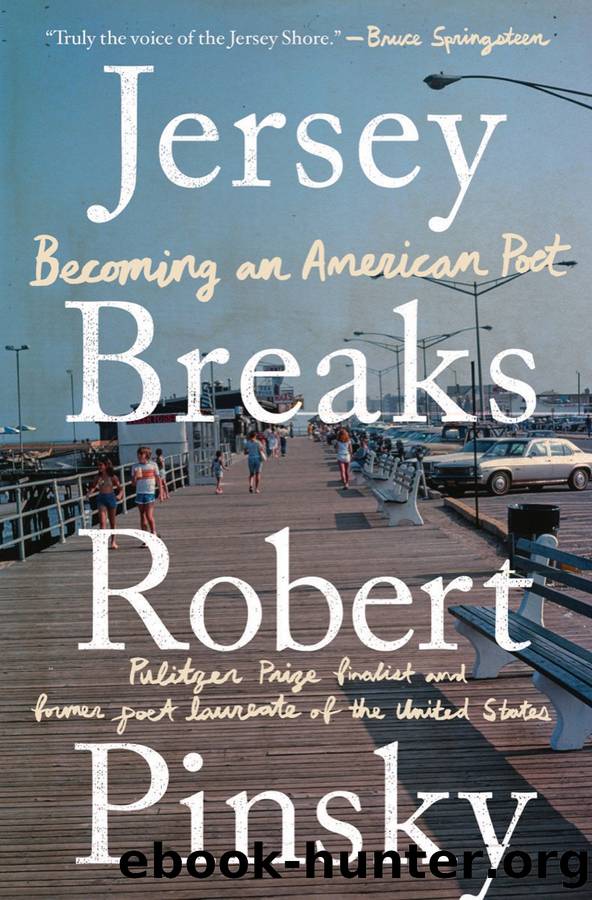

Jersey Breaks by Robert Pinsky

Author:Robert Pinsky

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

Published: 2022-08-29T00:00:00+00:00

XIII

Moving Around

LIFE STUDIES is Robert Lowellâs best-known and most influential book. It won the National Book Award for poetry in 1960. I read it in 1962 and I hated it. In a shallow way, my dislike was a matter of social class. I said aloud to Lowellâs book, âYeah, I had a grandfather, too.â Like my fellow would-be urban Beatniks at Rutgers, I preferred the manners of Allen Ginsbergâs âKaddishââthe poet reading the Hebrew prayer for the dead while listening to Ray Charles and walking the streets of Greenwich Village.

A year later, when I arrived as a graduate student at Stanford, I entered a culture more bucolic than what I had known at Rutgers, the State University of New Jerseyâthe home state of Ginsberg, with urban New Brunswick about an hour from those Village streets. Surrounding the sleepy Palo Alto of those days, an actual village, the future Silicon Valley was still a place of horse ranches and apricot orchards. Leland and Jane Stanford had founded the university on their ranch, in 1891, and the schoolâs affectionate nickname for itself was âthe Farm.â In Palo Alto, too, as in the quite different literary and urban terrain of Rutgers, Robert Lowellâs poetry was not held in the first rank of importance.

But five or six years later, in 1970, I took a job teaching at Wellesley College, not far from Boston and Cambridge, where I met poets who considered Life Studies a major work of art. For my impressive new friends Frank Bidart, Gail Mazur and Lloyd Schwartz, Lowell was the great living model of a poet. Life Studies had been transforming for them. A book I didnât like, and for years ignored, had opened new possibilities for people I admired.

Rejecting Life Studies on first encounter was partly a conventional reflex, an automatic dislike for inherited privilege. But the resistance I felt goes deeper, involving qualities of idiom and imagery, andâeven moreâtheir cultural implications. In the personal narratives and declarations of Life Studies, many readers valued a directness that for me lacked an antic, disjunctive quality I prized in American life and poetry. Lowellâs autobiographical poems felt humorless and foursquare. They were not enough like the movies of Mel Brooks or the eruptive comic strips of Walt Kelly.

It was not just social class. Leaving aside laugh-out-loud comedy, an example in poetry of what I mean is the work of Marianne Moore. The social voice in her poem âSilenceâ is not exactly working class or ethnic. On the contrary, that poem begins:

My father used to say,

âSuperior people never make long visits,

have to be shown Longfellowâs grave

or the glass flowers at Harvard . . .â

After quoting her fatherâs distinctly upper-middle-class assertion, Moore presents a memorably outlandish, inexplicable image for self-reliance: a cat with âthe mouseâs limp tail hanging like a shoelace from its mouth.â The image comes from left field, mixing different registers of attention (Longfellow, glass flowers, shoelace) with an insouciance I find inspiring. Lowell, I thought, would never come up with that cat.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4280)

Never by Ken Follett(3917)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3834)

Unfinished: A Memoir by Priyanka Chopra Jonas(3361)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3352)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3054)

Will by Will Smith(2891)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2339)

It Starts With Us (It Ends with Us #2) by Colleen Hoover(2316)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(2309)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(2289)

The Storyteller by Dave Grohl(2210)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(2208)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(2177)

The Becoming by Nora Roberts(2177)

The Stranger in the Lifeboat by Mitch Albom(2103)

Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr(2079)

Love on the Brain by Ali Hazelwood(2046)

Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson(1996)