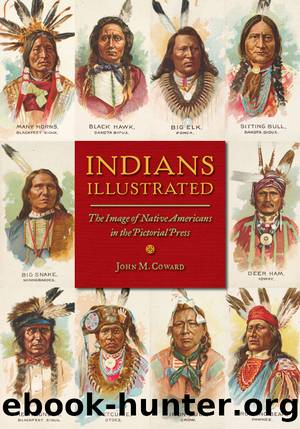

Indians Illustrated by John M Coward

Author:John M Coward [Coward, John M]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Social Science, General, Ethnic Studies, American, Native American Studies, History, United States, 19th Century, Media Studies

ISBN: 9780252098529

Google: qB-TDAAAQBAJ

Publisher: University of Illinois Press

Published: 2016-06-30T05:47:32+00:00

FIGURE 5.4. Responding to the death of Custer, Harperâs artist C. S. Reinhart produced contrasting panelsâthe romance of a West Point cadet and the fatal reality of Indian fighting in the West.

There was more such verse, some of it describing an Indian ambush in romantic terms:

Crack of rifle and savage yells!

Poisoned arrow and hissing shot

Pour from the ambush thick and hot.

Red blood, flowing from manly veins,

Dyes with crimson the burning plains.43

These words, and the illustrations they explained, were a highly fictionalized way of dealing with the loss of a military hero and the national grief that followed the news from the Little Bighorn. The Indian victory over Custer had impressed itself on the nation in a powerfully emotional way, so much so that Harperâs Weekly was moved to respond not with a realistic-seeming news illustrations of the Last Stand, but sentimentally and symbolically, with words and images that expressed the national mood. Reinhartâs contrasting images enlarged private love to the level of a national tragedy, simultaneously damning the savages and praising the fallen hero and his lost love. No Indians were shown in these illustrations and none was needed. It was enough for Harperâs Weekly to show an arrow piercing the officerâs body, a vivid reminder of the price Custerâand by extension, all American soldiersâwere paying as they attempted to subdue the savages and bring civilization to the northern plains.44

Invented Indian Violence

Unlike newsworthy war illustrations featuring Beever, Fetterman, and Custer, the pictorial press also featured other pictures of Indian-white violence that were wholly imaginary, unconnected to specific events. These illustrations were allegorical and ideological, constructed pictures of generic Indian-white conflict intended to tell larger stories of the American West. Freed from the facts, artists and illustrators could use their skills to imagine particularly dramatic moments that epitomized the national project of taming the West. One example of this sort of symbolism appeared as a full-page illustration in Harperâs in early 186645 (figure 5.5). This image showed two white riders, described as a âmounted messengers,â fleeing from a band of mounted, attacking Indians. As with Lieutenant Beeverâs death scene, this was a vivid and dramatic imageâeven the horses appear excited. The attacking Indians have already surrounded and killed one messenger; the other rider is firing back at his attackers with a pistol. The closest Indian, in fact, has been hit and is reeling on his mount. But the messenger is outnumbered; his situation appears desperate.

This illustration, based on a sketch by S. B. Enderton, was published without a story, a sign that it did not depict a specific Indian attack. As a symbolic fantasy, it included all the elements of an iconic scene of Indian-white violence, unambiguous visual components that would in time become a Western cliché. The white messengers (the good guys) were under attack from marauding Indians (the bad guys), who were unmistakable enemies of civilization. This was an apparent ambush, too, a tactic favored by the hostile tribes of the plains. For readers in eastern and midwestern cities

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11801)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8961)

Paper Towns by Green John(5173)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5172)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5070)

Industrial Automation from Scratch: A hands-on guide to using sensors, actuators, PLCs, HMIs, and SCADA to automate industrial processes by Olushola Akande(5042)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4289)

Be in a Treehouse by Pete Nelson(4028)

Never by Ken Follett(3928)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3839)

Goodbye Paradise(3795)

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro(3388)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(3377)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3364)

The Cellar by Natasha Preston(3328)

The Genius of Japanese Carpentry by Azby Brown(3281)

120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade(3255)

Reminders of Him: A Novel by Colleen Hoover(3067)

Drawing Shortcuts: Developing Quick Drawing Skills Using Today's Technology by Leggitt Jim(3063)