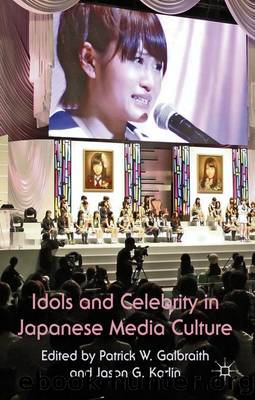

Idols and Celebrity in Japanese Media Culture by Patrick W. Galbraith & Jason G. Karlin

Author:Patrick W. Galbraith & Jason G. Karlin [Galbraith, Patrick W.]

Language: eng

Format: azw3

Publisher: Palgrave Macmillan Monographs

Published: 2012-05-31T16:00:00+00:00

6

The Homo Cultures of Iconic Personality in Japan: Mishima Yukio and Misora Hibari

Jonathan D. Mackintosh

In his entry “Who is a Gay Icon?” the Tenoru Gay Times blogmaster notes, “There is a word, gei aikon (gay icon). It probably comes from America. Although I’ve heard it … I’m unfamiliar with it” (Maruyama 2008). The blogmaster’s uncertainty highlights two ambiguities characterizing male gay culture in Japan. While it is evident that some celebrities—for example, pop singer Matsuda Seiko—hold special appeal for gay men, it isn’t wholly clear why their “charisma” is such that they attract the “worship” specifically of these men.Z1 What is it about being gay that these so-called icons articulate?

Furthermore, is the imported concept of the “gay icon” even meaningful? Indeed, it is a 1970s neologism emerging as a project of that decade’s Anglo-American Movement for Gay Liberation: visible and representative of gay value, the admirable qualities and special accomplishments of highly visible celebrated individuals were deployed to act as a rallying point in the political resistance of gay people against their oppression (Dyer 2009, 12–14, 16). In contrast to this movement, which was “pivotal in making homosexual identity” (Rosenfeld 2003, 3), Japanese projects to effect similar change were limited, giving voice to some but hardly providing an axiomatic political model of identity for the vast majority of men-loving-men or the wider Japanese population (cf., McLelland 2000, 222–240).

Nonetheless, it is overly pessimistic to write off the concept of “gay icon” as irrelevant to Japan. As this chapter will demonstrate, what I shall refer to as the “homo cultures of iconic personality” are of historical and cultural analytical use. In their definition, they describe a defining moment in the early 1970s for the history of male homosexuality, or, as it was known in the culture of men-loving-men in Japanese at that time, homo. Between 1971 and 1975, Japan’s first commercial and nationally distributed magazines by and for homo appeared,2 and in the pages of Barazoku (founded 1971), Adonis Boy (1972), Adon (1974), and to a lesser extent Sabu (1974), aspiration was often palpable. In entering into the Japanese mediascape, these magazines sought to mobilize homo identity and effect community consciousness, and, most far-reaching, advocated a political space to affirm the legitimacy and equality of homo in the Japanese public sphere. Despite the momentary high profile of homo, modern jōshiki (heterosexual normality)3 remained steadfast, homo activity returned to being largely invisible, and homo-phobic society went unchanged (Minami 1991, 130). The homo cultures of iconic personality are not the only factors that explain the nonemergence of a unified voice in the 1970s moment. But, in the diversity of priority and aspiration that these cultures reflected, we can begin to understand why, in the early 1970s, the homo history of Japan evolved largely in contradistinction to that of the Anglo-American West—despite the fact that both histories emerged out of a global synchronicity of capitalist modernity.

Specifically, the celebration in the homo magazines of two contemporary personalities illustrates divergent homo historical trajectories that give insight into the ambiguities characterizing the male homosexual experience in Japan.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Papillon by Henry Charrière(796)

Watercolor With Me in the Forest by Dana Fox(589)

The Story of the Scrolls by The Story of the Scrolls; the M(556)

This Is Modern Art by Kevin Coval(459)

A Theory of Narrative Drawing by Simon Grennan(456)

Frida Kahlo by Frida Kahlo & Hayden Herrera(445)

Boris Johnson by Tom Bower(443)

Banksy by Will Ellsworth-Jones(435)

AP Art History by John B. Nici(429)

Van Gogh by Gregory White Smith(426)

Draw More Furries by Jared Hodges(423)

The Art and Science of Drawing by Brent Eviston(423)

Glittering Images: A Journey Through Art From Egypt to Star Wars by Camille Paglia(420)

War Paint by Woodhead Lindy(414)

Scenes From a Revolution by Mark Harris(413)

100 Greatest Country Artists by Hal Leonard Corp(391)

Ecstasy by Eisner.;(386)

Young Rembrandt: A Biography by Onno Blom(374)

Theater by Rene Girard(355)