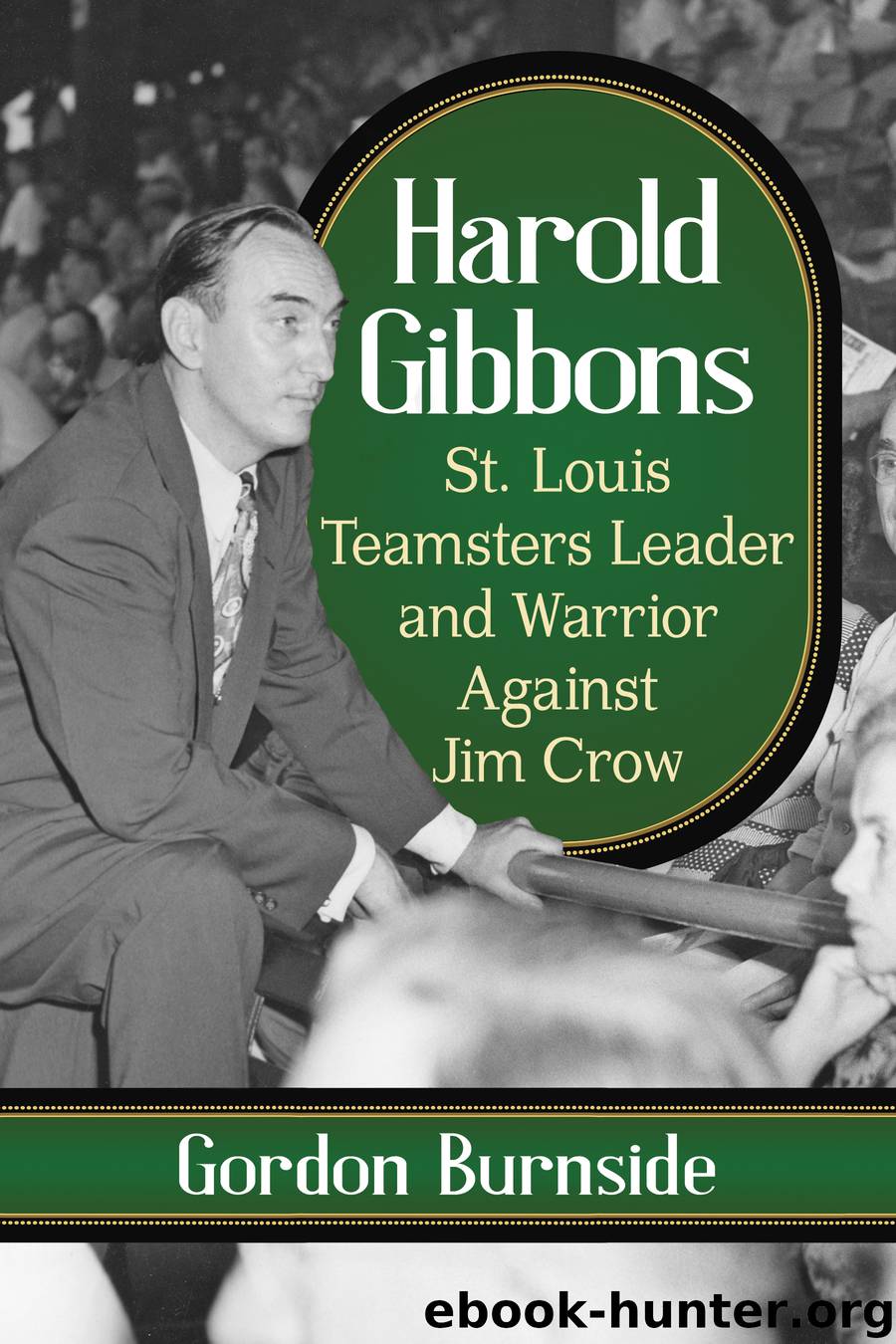

Harold Gibbons by Gordon Burnside

Author:Gordon Burnside

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: McFarland

Published: 2018-09-17T16:00:00+00:00

16

The Split

On Friday, November 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas.

Jimmy Hoffa happened that day to be out of town, in Miami. Harold Gibbons was in charge of the union’s Washington, D.C., headquarters. When the news came in, Gibbons was winding up a late lunch at Duke Ziebart’s Restaurant with the lawyer Edward Bennett Williams. He raced back to the Marble Palace to find that a tearful Larry Steinberg had already lowered the flag and sent employees home. Having approved Steinberg’s actions, Gibbons wired a message of condolence to the Kennedy family and ordered the building closed for the funeral. Then he called Hoffa to fill him in.1

“He raised hell with me for having done it,” Gibbons said years afterward. “He cursed the Kennedys—this was two hours after the guy had been shot—and he cursed me. And finally, after he screamed for a while, I told him, ‘When you get back get yourself a new boy because I’m not going to be here. I’m resigning.’ This for me was the last straw.”2

It wasn’t quite. Gibbons didn’t actually leave IBT headquarters for another six weeks, and for years thereafter he and Hoffa would collaborate on projects from time to time. But nothing like their early, easy relationship would be restored until after Hoffa was released from prison in 1971, eight years later.

There were some who said Gibbons merely used the Kennedy assassination as a pretext for splitting from Hoffa. One such person was Ron Gamache, Gibbons’ eventual successor as secretary-treasurer of Local 688. “He [Gibbons] realized he couldn’t keep sitting across the desk from the man [Hoffa] he had been secretly working against,” said Gamache.3 Of course by the time Gamache said this, Gibbons, once his mentor, had become an enemy.

For five years, from 1958 to 1963, the Hoffa-Gibbons relationship had been functional enough to let the two not only work together in the Marble Palace but also live together at the Woodner Hotel. It wasn’t surprising that the partnership eventually fractured. The interesting question is: how had they kept it working so well so long?

Gibbons often described Hoffa as a great labor leader, and he probably meant it. His model in that respect was John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers. While in Washington, Gibbons’ children said, he rarely missed an opportunity to drive out to Lewis’ retirement home in nearby Alexandria, Virginia, to listen to the old man’s reminiscences.4 Gibbons admired Lewis for his role in creating the CIO, but even more, perhaps, for Lewis’ insistence on calling a series of coal strikes in 1943, in the middle of the Second World War. Lewis was widely hated for it. Gibbons had spoken in praise of Lewis and the strikes at the time (see Chapter 4). Lewis, he saw, recognized no human authority higher than his own—not Congress’, not even Franklin Roosevelt’s.

Way back in 1958, when Hoffa was just starting to become something of a frightening figure to many in this country, Daniel Bell, Fortune magazine’s labor expert, argued that such fear was groundless.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Mid Atlantic | Midwest |

| New England | South |

| West | Kindle Edition |

| Large Print | Audible Audiobook |

| Audio CD | Board Book |

Kitchen confidential by Anthony Bourdain(2323)

Dry by Augusten Burroughs(1692)

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou(1594)

Kitchen Confidential by Anthony Bourdain(1533)

KITCHEN CONFIDENTIAL Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly by Anthony Bourdain(1453)

A Child Called It by Dave Pelzer(1411)

I know why the caged bird sings by Maya Angelou(1376)

A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius by Dave Eggers(1366)

Taken by J. C. Owens(1282)

all by Unknown Author(1244)

Zeitoun by Dave Eggers(1228)

Extraordinary, Ordinary People by Condoleezza Rice(1210)

House of Darkness House of Light by Andrea Perron(1159)

A Stolen Life by Dugard Jaycee(1157)

The Farm in the Green Mountains by Alice Herdan-Zuckmayer(1143)

Law Man by Shon Hopwood(1142)

The Big Sea by Langston Hughes(1095)

The Year of Yes by Maria Headley(1070)

Dewey: the Small-Town Library Cat Who Touched the World by Vicki Myron & Bret Witter(1016)