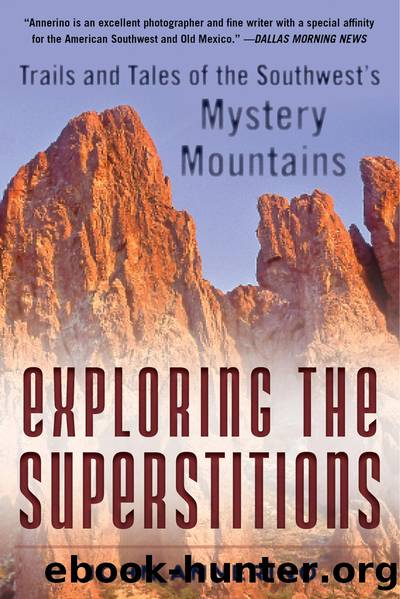

Exploring the Superstitions by John Annerino

Author:John Annerino

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781510723740

Publisher: Skyhorse

Published: 2017-12-07T00:00:00+00:00

When about two-thirds of the [Apache] band had been killed or maimed by the hail of bullets fired at them [by âthe settlersâ], the remainder became panic stricken and retreated in the only direction possibleâtoward the westerly edge of the mountain which on that side, broke off abruptly into sheer cliffs, hundreds of feet high.

Without a momentâs hesitation, the fleeing [Apache] . . . threw themselves over the towering cliffs, in the faint hope of escaping fatal injury. But the leap into space was too great . . . The entire Apache bandâsome 75 in number [âmen, woman, and childrenâ]âwere wiped out . . . From that time the Big Picachoâgrim and forbiddingâhas been known as Apache Leapâa most appropriate name, perpetuating, as it does, a tragic incident in the early history of Arizona,â wrote Barney, then recognized as the âunofficial historian for Arizona.â

Historians later scoffed at Barneyâs story because there were no official military records, as was case for the April 30, 1871 Camp Grant Massacre when Tucsonâs âCommittee of Public Safetyâ killed, scalped, and burned 144 Apache elders, men, women, and children; and the December 28, 1872 Skeleton Cave Massacre when US Troops under the command of General George Crook cut down seventy-six to ninety-six Yavapai elders, men, women, and children cornered in a Salt River Canyon alcove. Moreover, Barney had also written in his Arizona Highways feature: âAt daybreak, the settlers made a sudden and determined attack upon the surprised and bewildered Apaches, and wrought terrible havoc among them and their first volleys.â Given the record of Camp Grant, Skeleton Cave, and the 1866 planned âexterminate[ion]â of 123 distant Yavapai by the Arizona Volunteers on the Santa Maria River and Skull Valley, why would unaffiliated âsettlersâ provide a detailed account of the alleged slaughter of what one San Carlos Apache writer recently wrote was eighty people?

If the barbaric Apache Leap incident wasnât reported by territorial newspapers, witnesses, and historians, it doesnât mean the event did not happen. And, if it had been noted or reported, it does not mean it would have been told in the manner in which the incident unfolded. Based on the massacres at Camp Grant, Skeleton Cave, Skull Valley, and elsewhere throughout the territory where, in 1805, Spanish troops under the command of Lieutenant Antonio Narbona annihilated 115 Navajo elders, women, and children hiding in the Cañon del Muerto tributary of Canyon de Chelly, Iâm convinced Apache Leap did occur. In the oral tradition of the San Carlos Apache, the tragic, but noble defeat of the Apache standing their ground against all odds is still passed down from one generation to the next 150 years later.

During San Carlos Apache Tribal Chairman Wendsler Nosie Sr.âs November 1, 2007 testimony before the US House Natural Resources Committee regarding âforeign owned mining giantsâ to open pit mine on sacred Apache ground, he testified: âThe escarpment of Apache Leap, which towers above nearby Superior, is also sacred and consecrated ground for our People . . . You

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7301)

The Plant Paradox by Dr. Steven R. Gundry M.D(2596)

The Stranger in the Woods by Michael Finkel(2508)

Miami by Joan Didion(2354)

Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail by Cheryl Strayed(2243)

INTO THE WILD by Jon Krakauer(2187)

Trail Magic by Trevelyan Quest Edwards & Hazel Edwards(2166)

DK Eyewitness Top 10 Travel Guides Orlando by DK(2163)

Vacationland by John Hodgman(2119)

The Twilight Saga Collection by Stephenie Meyer(2115)

Nomadland by Jessica Bruder(2050)

Birds of the Pacific Northwest by Shewey John; Blount Tim;(1956)

The Last Flight by Julie Clark(1938)

Portland: Including the Coast, Mounts Hood and St. Helens, and the Santiam River by Paul Gerald(1908)

On Trails by Robert Moor(1887)

Deep South by Paul Theroux(1819)

Blue Highways by William Least Heat-Moon(1756)

Trees and Shrubs of the Pacific Northwest by Mark Turner(1706)

1,000 Places to See in the United States and Canada Before You Die (1,000 Places to See in the United States & Canada Before You) by Patricia Schultz(1634)