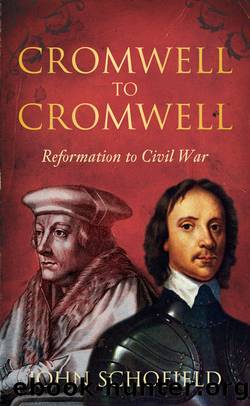

Cromwell to Cromwell: Reformation to Civil War by John Schofield

Author:John Schofield [Schofield, John]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: history, Europe, Great Britain, General, Military, Wars & Conflicts (Other)

ISBN: 9780752466569

Google: rJETDQAAQBAJ

Publisher: The History Press

Published: 2011-07-30T00:14:30.667523+00:00

5

CHARLES I, 1625â42

KING AND COMMONS

The eldest son of James and Anne was an athletic, handsome, intelligent and cultured Protestant prince, seemingly born to reign. Yet the young man who would have been King Henry IX died tragically from typhoid in November 1612, leaving his younger brother, Prince Charles, heir to the throne of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland. James did his best to prepare Charles for his future role. The old kingâs Basilikon Doran, a book of instruction and guidance originally penned for Henry, was passed on to Charles. James had also written a set of pious meditations on St Matthewâs Gospel to âput inheritors to kingdoms in mind of their callingâ. The prince was bid to love God and uphold the true religion, to govern always for the welfare of the nation in a manner worthy of one who has received his commission from God.1

Charles was a somewhat non-communicative, private man, prone to be easily offended. Nevertheless, his accession in March 1625 was generally welcomed by his people, not least because of the collapse of the unpopular proposed Spanish marriage and his own recently discovered hostility towards Spain. Charlesâs marriage to Henrietta Maria was well received. Neither Parliament nor the people had the remotest idea that their new king had promised the French he would grant freedom of worship to papists. In an ingenious piece of official disinformation, it was spread around that the new queen might be on the verge of converting to the Protestant faith. So when Charles and his bride drove through London in June 1625, a warm and affectionate welcome greeted them.2

Despite the goodwill of the nation towards him, Charlesâs first parliament, which first met in June, did not proceed agreeably. Most members, blissfully ignorant of the pledge Charles had made to the French, were determined that the recusancy laws against Catholics ought to be enforced, even strengthened. Then Charles, though supposed to be a supporter of war against Spain, declined in his opening speech to spell out exactly what his war policy would cost, or even what his precise plans were. Because the Commons was sympathetic in principle to helping foreign Protestants against the Catholic forces, Charles was offered a subsidy, but it was a mere tenth of the amount that Charles really needed had he been in earnest. King and Commons were not on the same wavelength. The Commons was expecting a naval war to plunder Spanish ships, which, it fondly hoped, would cost little and yield a great deal; but following the French marriage treaty, Charles and Buckingham were thinking of a land campaign as well.3

The first parliament then looked as though it would peter out. Charles decided he would end it on the apparently considerate grounds that London was afflicted by plague, and many members were anxious to leave for the safety of the shires. But before all the members had left, Sir John Coke, put up to it by Buckingham, let the sixty or so members still

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4292)

Never by Ken Follett(3937)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3848)

Unfinished: A Memoir by Priyanka Chopra Jonas(3381)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3370)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3072)

Will by Will Smith(2908)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2352)

It Starts With Us (It Ends with Us #2) by Colleen Hoover(2341)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(2323)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(2300)

The Storyteller by Dave Grohl(2228)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(2219)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(2196)

The Becoming by Nora Roberts(2188)

The Stranger in the Lifeboat by Mitch Albom(2113)

Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr(2098)

Love on the Brain by Ali Hazelwood(2059)

Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson(2009)