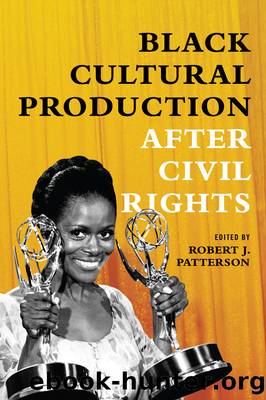

Black Cultural Production after Civil Rights by Robert J Patterson

Author:Robert J Patterson [Patterson, Robert J]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780252084607

Barnesnoble:

Publisher: University of Illinois Press

Published: 2019-08-06T00:00:00+00:00

Conclusion: âInto the Revolutionâ

Kay Lindseyâs call for black women to âproject [them]selves into the revolution,â encapsulates the emphasis on agency, militancy, and self-assertion affirmed by the cultural workers of the 1970s.60 As a final example, June Jordanâs His Own Where (1971) imagines more sustainable models of equality and mutually constitutive support within black communities. His Own Where presentsâwithout shame or censoriousnessâthe sexually active romance between Buddy and Angela, two teens left to fend for themselves as a result of absent or abusive parenting. Their relationship is romantic, mutually supportive, and far more stable than any adult interaction in their lives. The novel celebrates black vernacular and emphasizes the importance of self-empowerment even as it also participates in the larger cultural conversations about domestic abuse within black families, methods of black activism, and the limits of militancy. Militancy infuses even their playful navigation of the city, as Buddy âseem[s] like a commando on the corner. ⦠Arms like a rifle in rotation.â61 But, damningly, militancy does Angela no good when she is at home and her father beats her: âAngela struggle her hand under the pillow where to protect herself she hide a kitchen knife not to be beaten like she is. Seize the handle, ship the knife into his view and tell him âLeave me aloneââ (28). Nevertheless, her father quickly disarms her and abuses her so terribly that she is hospitalized. Though Angela is admirable for her attempted self-defense, her inability to single-handedly combat patriarchal force convinces her to develop a cooperative and nonviolent bond with Buddy.

Buddy is a role model for a new, progressive, and cooperative black male partner. He takes Angela to the hospital after her fatherâs beating and helps her to obtain legal protection. At school, he organizes a protest to demand sex education. His platformââWant to learn anatomy ⦠contraceptives ⦠sex free and healthyââcould come from the womenâs sexual liberation movement (37). In the dining hall, he organizes another protest against the poor food and dehumanizing conditions: âYou pack us in like animals, and then you say, they act like nothing more than animals. To hell with your controlâ (41). Here Buddy is thoroughly disruptive, yet brilliantly nonviolent: he organizes a dance between 700 students and the four matronly lunch ladies, who have the time of their lives. The police, called to rush the lunch room, are loathe to end the womenâs fun and refuse to find fault in the situation. In short, Buddy models a black activism that is more attentive to black womenâs endangerment and respectful of black womenâs pleasuresâsocial as well as sexualâas a corrective to the misogyny and regressive patriarchal demands of much Black Power discourse about gender relations.

Simultaneously charmingly immature and adult beyond his years, Buddy devotes himself to Angela and espouses the importance of respectingâand lovingâwomen, in stark contrast to the âhostilityâ in black menâs approach toward black women that Fran Sanders excoriated in âDear Black Man.â As part of his ability to forge a black activism that

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(10505)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(7539)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(4188)

Paper Towns by Green John(4163)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3788)

Be in a Treehouse by Pete Nelson(3204)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3023)

Goodbye Paradise(2948)

Never by Ken Follett(2868)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(2693)

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro(2613)

The Genius of Japanese Carpentry by Azby Brown(2601)

The Cellar by Natasha Preston(2591)

Drawing Shortcuts: Developing Quick Drawing Skills Using Today's Technology by Leggitt Jim(2525)

120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade(2426)

Architecture 101 by Nicole Bridge(2348)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(2289)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(2261)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(2058)