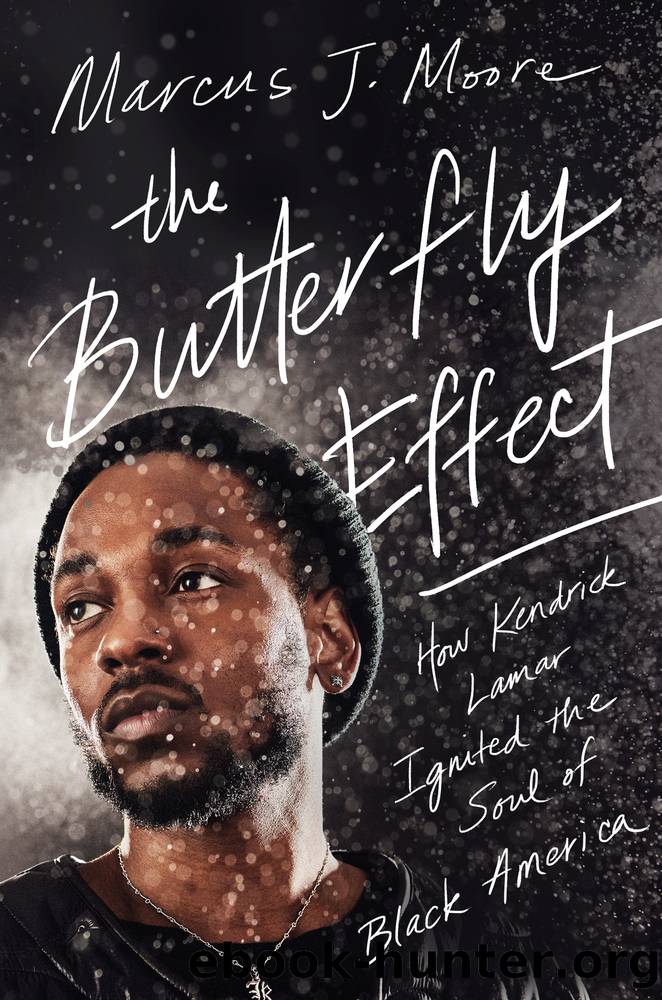

The Butterfly Effect by Marcus J. Moore

Author:Marcus J. Moore

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Atria Books

Published: 2020-10-13T00:00:00+00:00

* * *

In December 2014, singer DâAngelo set the bar for what black protest music was supposed to sound like in the modern era. Black Messiah, his long-awaited and often-delayed third studio album, was released on the evening of the fifteenth, and through it came the anger, helplessness, and misery of being a black person in 2014, and watching your brothers and sisters be gunned down in the streets. Just like Kendrick, DâAngelo had been dubbed the savior of his genre (in this case R&B) after his 2000 album, Voodoo, was released to widespread acclaim. With its grainy black-and-white coverâa crowd of uplifted black handsâBlack Messiah responded directly to the uprising in Ferguson and the grand jury decision in Staten Island. Also like Kendrick, DâAngelo spoke only through his music; you were unlikely to hear from him if he didnât have music to promote. Black Messiah wasnât entirely protest music; the songs âReally Loveâ and âAnother Lifeâ were sugary soul ballads akin to what heâd performed in the mid-1990s as a laid-back crooner with a leathery voice and cornrowed hair.

Elsewhere on the album, though, DâAngelo spoke to the pain that black people felt everywhere. On âThe Charade,â he sings: âAll we wanted was a chance to talk / âStead we only got outlined in chalk.â Then there was â1000 Deaths,â a murky, psychedelic rock track about being sent to, and being prepared for, war. The battle itself was up for interpretation; it could refer to a fight in a foreign land or one closer to home. And with lyrics like âI wonât nut up when we up thick in the crunch / Because a coward dies a thousand times / But a soldier only dies just once,â it was perhaps the most revolutionary track in the singerâs discography. At that point, musicians were releasing Ferguson-influenced songs here and there, though not a full-scale record that addressed the wide-ranging despair within the black community. âWhen was the last time someone of [DâAngeloâs] stature came out with a political record?â Russell Elevado, a recording engineer and frequent DâAngelo collaborator, once asked Red Bull Music Academy. âNo one is talking about any social issues. Letâs bring that back, too.â Black Messiah harkened back to records like Sly and the Family Stoneâs Thereâs a Riot Goinâ On and Curtis Mayfieldâs Curtis, as meticulous funk and soul with black plight at the center. Musicians like Sly, Curtis, and DâAngelo spoke to us and for us. They created music in which we could see our full, beautiful selves, and they helped us remember that we werenât second-class citizens, even when the world tried to render us invisible. America can beat you down if you let it, but through Slyâs howl, Curtisâs falsetto, and DâAngeloâs hum, you felt the beauty and bleakness of black culture. Sometimes thatâs what protest is. It isnât solely about picket signs and clever chants, itâs about the full breadth of the experience, about wading through the misery and finding light through it all.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

I Have Something to Say by John Bowe(3493)

Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson(2003)

What Happened to You? by Oprah Winfrey(1760)

Doesn't Hurt to Ask by Trey Gowdy(1631)

Solutions and Other Problems by Allie Brosh(1319)

American Dreams by Unknown(1277)

Disloyal: A Memoir by Michael Cohen(1226)

The Silent Cry by Cathy Glass(1157)

Talk of the Ton by unknow(1050)

Infinite Circle by Bernie Glassman(1046)

Don't Call it a Cult by Sarah Berman(1030)

Group by Christie Tate(1028)

Home for the Soul by Sara Bird(1017)

Before & Laughter by Jimmy Carr(887)

The Book of Hope by Jane Goodall(859)

Severed by John Gilmore(858)

Ghosts by Dolly Alderton(858)

Total F*cking Godhead by Corbin Reiff(847)

Searching for Family and Traditions at the French Table by Carole Bumpus(810)