The Arab Imago by Stephen Sheehi;

Author:Stephen Sheehi;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Princeton University Press

Published: 2021-11-15T00:00:00+00:00

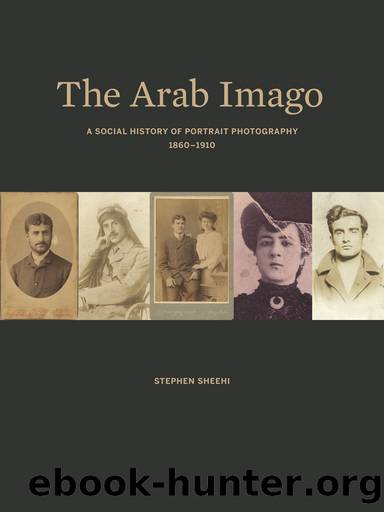

Figure 46. G. Kirkorian, Ê¿Asim Effendi Mudir al-Tahrirah, AH 1305 (1887), carte de visite given to Bishara Effendi Habib.

Figure 47. G. Krikorian & G. Saboungi, Ê¿Asim Effendi Mudir al-Tahrirah, Jerusalem and Jaffa, AH 1308 (1890), carte de visite given to Bishara Effendi Habib.

Portraitsâ Currency

âThe photographic portraiture,â Vincent Rafael tells us in speaking of photography in the Philippines, âwas meant not only to convey the personâs likeness but to situate it in relation to the viewer. Such was the function of the dedications . . . addressed to specific recipients, evoking a sense of intimacy between sender and receiver.â28 The dedications and signatures on the cartes de visite of Jawhariyyehâs first album bear the stain of sentiment, intimacy, and social history. They trace vectors and connections essential to Palestinian social and political relations. Among the first pages of Jawhariyyehâs Tarikh are three images of an enigmatic Ê¿Asim Effendi, âdirector of the registryâ (mudir al-tahrirah). The first image is a close head shot vignette taken by Garabed Krikorian (fig. 46). It is dated AH 1305 (1887), the end of the administration of Raʾuf Pasha, mutasarrif of Jerusalem. Adjacent to this portrait, there is a second carte de visite of Ê¿Asim Effendi, this time produced by G. Krikorian & G. Saboungi, who co-owned a studio in Jaffa (fig. 47).

While the Krikorian and Saboungi portrait is more groomed, compositionally and in content, the soft head vignette formalistically conveys a subjective depth that precisely illustrates the verum factumâs tension. In the end, little is known about Ê¿Asim Effendi. He could be the person with the same name who was lieutenant governor of Jerusalem in the early 1890s. If this is the case, his dedication and relation to Bishara Habib is telling. Bishara Effendi Habib was a high-ranking functionary in Raʾuf Pashaâs office and mainstay in the office of the mutasarrif, outlasting in the Jerusalem administration an assortment of subsequent governors. Ê¿Asimâs sentiment of loyalty and appreciation to Habib is better understood when one remembers that Raʾuf Pasha attempted to dislodge both of Jerusalemâs rival, leading families, al-Husaynis and al-Khalidis, from municipal and judicial positions that they had dominated for centuries, calling them âparasitesâ on the peasantry.29 This is perhaps evidence that the image is certainly not Ê¿Asim Effendi al-Husseini. In the narrative of Arab nationalism, this attempt was spun anachronistically as an attempt to Turkify the administration of the sanjak. More accurately, however, Raʾuf Pasha was implementing governmental policies to curb notablesâ power in rationalizing principles of Ottoman governance. Simply put, he was attempting to implement the same forms of Osmanlilik governmentality that were being extended throughout the empire.30 Ê¿Asim Effendi shared a social network with Bishara Effendi Habib, who as secretary and interpreter to successive governors, was an established functionary, with a degree of influence, if not power.31

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11329)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8402)

Paper Towns by Green John(4805)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(4791)

Industrial Automation from Scratch: A hands-on guide to using sensors, actuators, PLCs, HMIs, and SCADA to automate industrial processes by Olushola Akande(4621)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(4590)

Be in a Treehouse by Pete Nelson(3651)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(3645)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3612)

Never by Ken Follett(3535)

Goodbye Paradise(3455)

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro(3143)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(3132)

The Cellar by Natasha Preston(3078)

The Genius of Japanese Carpentry by Azby Brown(3041)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(2953)

120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade(2943)

Drawing Shortcuts: Developing Quick Drawing Skills Using Today's Technology by Leggitt Jim(2943)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(2811)