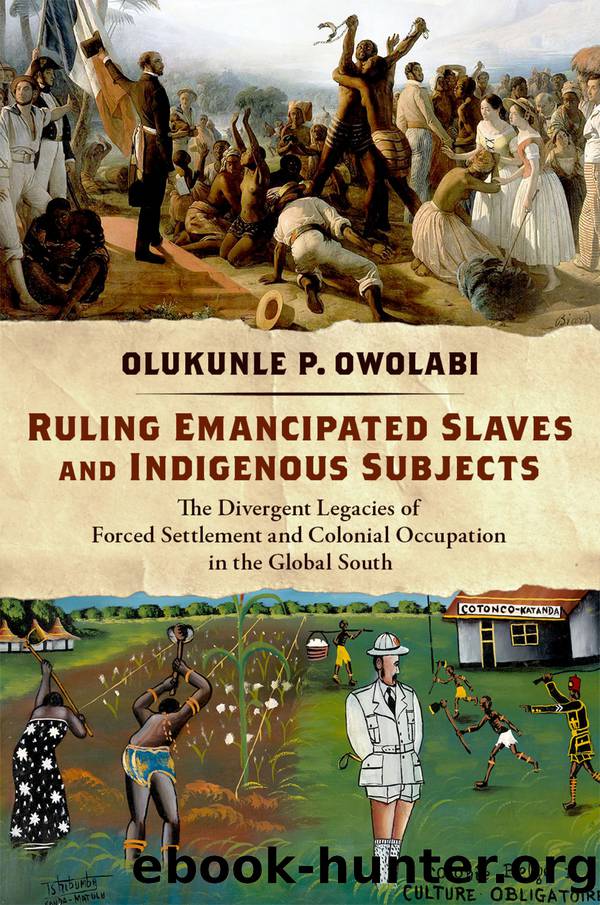

Ruling Emancipated Slaves and Indigenous Subjects by Olukunle P. Owolabi

Author:Olukunle P. Owolabi

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Published: 2023-08-15T00:00:00+00:00

Guinea-Bissau

Guinea-Bissauâs bifurcated colonial state and exclusionary citizenship policies severely restricted educational access to indigenous African subjects under Portuguese control. Only civilisado (i.e., Creole) children were permitted to attend public schools in Portuguese Guinea, which had the lowest levels of primary school enrollment in Portuguese Africa. Only 303 children were enrolled in official public schools in Portuguese Guinea at the beginning of the twentieth century (Portugal, Ministerio dos Negocios da Marinha e Ultramar 1905). There are no census records from this time period, but the World Christian Encyclopedia estimates a population of 120,000 inhabitants in Guinea-Bissau in 1900 (Barrett, Kurian, and Johnson 2001). This suggests that primary school students accounted for about 0.25% of the colonyâs population, or 1% of the school-aged population. Because the administrative capacity of the colonial state was so limited, official census records only provide information on the civilisado population of Portuguese Guinea. Between 1910 and 1938, primary school enrollment hovered around 700 students each year (Guiné 1910; Portugal, Instituto Nacional de EstatÃstica 1950), and the first secondary school only established in 1958 (Pombo-Malta 2006, 2). Thus, for most of the colonial era, Guinean Creoles, including the independence hero Amilcar Cabral, had to pursue their secondary education in Cape Verde (Davidson 1989, 65).

Restrictive citizenship laws further limited educational opportunities for indigenous African subjects in Portuguese Guinea. The colonyâs secular public schools only catered to Creole children, and indigenous African children were relegated to Catholic mission schools that emphasized catechism and manual labor. Catholic mission schools did not prepare students for the entrance examination that was required for secondary school (Patinha 1999, 38â40; Duffy 1961, 298).15 Consequently, there was no possibility for indigenous Africans to gain access to secondary schools. Secondary schooling for indigenous Africans was clearly not a priority for Portugalâs ecclesiastical hierarchy. As late as 1960, the archbishop of Lisbon maintained that Catholic mission schools should âteach the natives to write, to read and to count, but not . . . make them doctors!â (Ferreira 1974, 113). For most of the colonial era, Catholic missionary evangelization remained limited in Portuguese Guinea, and the Catholic Church maintained a state monopoly over the education of indigenous Africans. Nevertheless, there were only nine Catholic mission schools with a limited teaching staff of 16 priests and 14 nuns in the entire country in 1940 (Teixiera da Mota 1954, 116). By 1950, about 1,000 indigenous African children were enrolled in 45 Catholic mission schools (Pombo-Malta 2006, 165), whereas 10 state schools provided primary education for 700 Creole students (Portugal, Instituto Nacional de EstatÃstica 1959). Consequently, there were only 1,700 primary school students in a colonial state with more than 500,000 inhabitants.

Restrictive citizenship laws also hindered the expansion of education and literacy in Guinea-Bissau relative to Cape Verde. In 1950, Guinea-Bissau had the lowest adult literacy rate in the world, at 1%. Amazingly, UN data suggests that 55% of Guinean Creole (i.e., civilisado) adults were literate in 1950, compared with 0% for indigenous Africans (United Nations 1963, 303â4). At the same time, Portuguese census records claimed that 0.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Comparative | Conflict of Laws |

| Customary | Gender & the Law |

| Judicial System | Jurisprudence |

| Natural Law | Non-US Legal Systems |

| Science & Technology |

American Kingpin by Nick Bilton(3875)

Future Crimes by Marc Goodman(3592)

The Meaning of the Library by unknow(2564)

Inside the Middle East by Avi Melamed(2349)

Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty by Daron Acemoglu & James Robinson(2285)

On Tyranny by Timothy Snyder(2227)

Living Silence in Burma by Christina Fink(2061)

Putin's Labyrinth(2016)

The Mastermind by Evan Ratliff(1933)

The Smartest Kids in the World by Amanda Ripley(1847)

Think Like a Rocket Scientist by Ozan Varol(1813)

Law: A Very Short Introduction by Raymond Wacks(1738)

It's Our Turn to Eat by Michela Wrong(1725)

The Rule of Law by Bingham Tom(1690)

Philosophy of law a very short introduction by Raymond Wacks(1666)

Leadership by Doris Kearns Goodwin(1632)

A Dirty War by Anna Politkovskaya(1626)

Information and Communications Security by Jianying Zhou & Xiapu Luo & Qingni Shen & Zhen Xu(1611)

Civil Procedure (Aspen Casebooks) by Stephen C. Yeazell(1554)