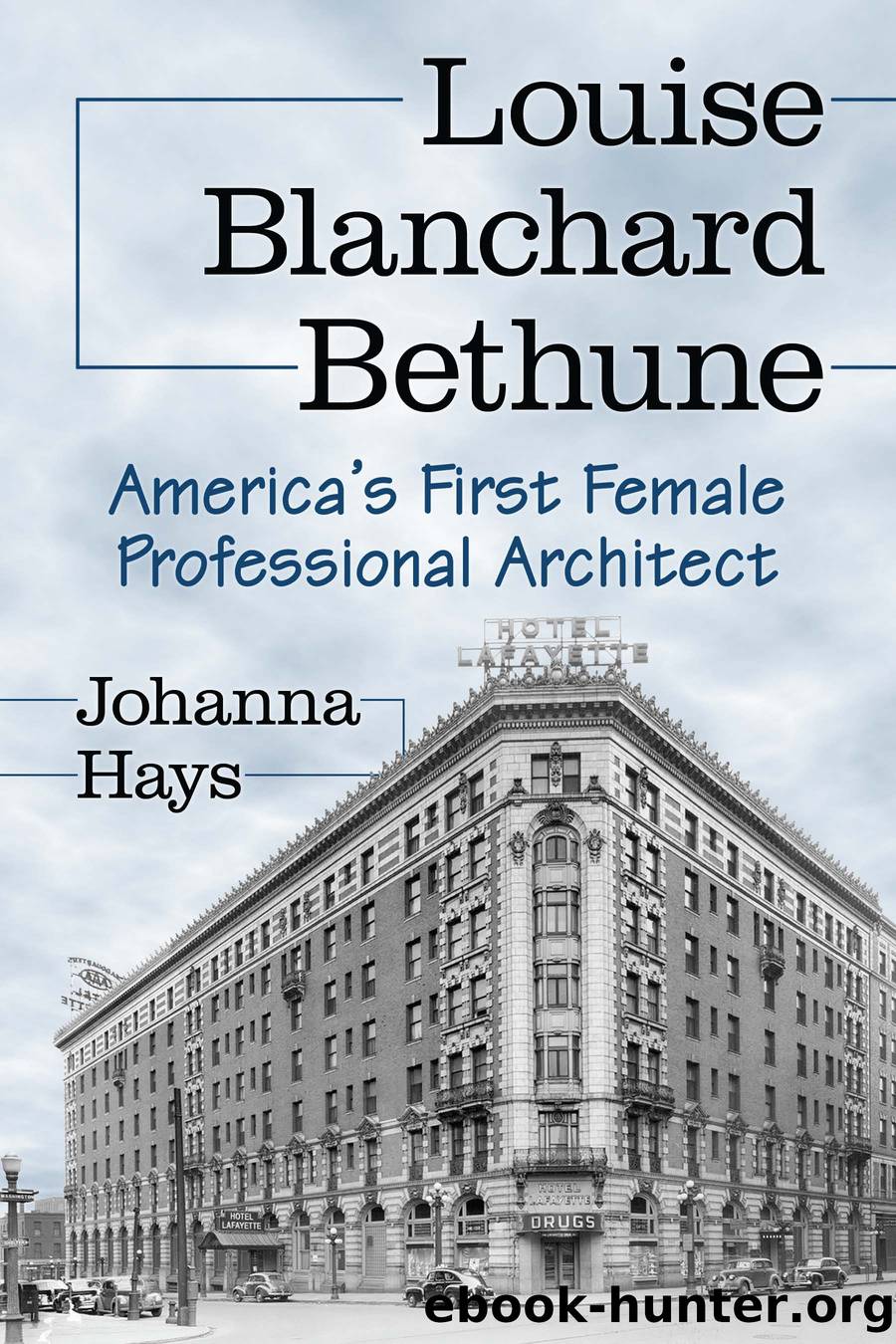

Louise Blanchard Bethune by Johanna Hays

Author:Johanna Hays

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Published: 2014-02-10T00:00:00+00:00

âFrank Irving Cooper1

This statement is from the textbook used by Columbia Universityâs architecture program, published in 1910, which was the year Columbia allowed women in its architecture program. The statement describes very well Bethuneâs sensitivity in her innovative work in creating appropriate designs for school buildings more than a quarter century earlier. She worked in collaboration with Buffaloâs superintendent of schools, James F. Crooker, who was committed to quality education and a safe environment for the public school students. These schools designed in the 1880s serve as the model for our current standards.

It was the first full year of Bethuneâs practice when Superintendent Crooker was elected along with progressive mayor Grover Cleveland in the wake of a mayoral scandal. Bethune and Superintendent Crooker were dedicated to creating a new standard in school buildings that emphasized health and safety over expediency or lavish symbolism. Superintendent Cooker served from 1882 till 1892, when he became New Yorkâs state head of education, serving 1892â1895. As New York State superintendent of schools, Crooker pushed through a statewide attendance law in 1894 and attempted to standardize teacher education.

With Crookerâs commitment to the health and safety of students and not just the âwarehousingâ of them to keep them off the streets, Bethune created school buildings safeguarded against fire that included the most current sanitary engineering and central heating long before solutions to this issue had been established. Her schools were done within budget and these buildings set standards for school buildings followed for decades afterwards.

The reality Crooker faced when he became school superintendent for Buffalo was that Buffaloâs thirty-five school districts had fifty-five buildings, thirteen rented buildings that were âa disgrace to the city,â and none acceptable for use by children and teachers. The rented spaces were in houses, stores, warehouses, and farm buildings. Some were in such bad condition he felt they were offered to the city when no longer suitable for farm animals. The city-owned school buildings were only slightly better, described by Crooker as at best substandard.2

Unfortunately the iconic little red schoolhouse was largely mythical in the nineteenth century. Cities were not clear on their responsibility for the development of public education. Education was considered important, but grew out of a tradition of private support. Wealthy citizens had schools built and others donated buildings, but along with this privatization came a situation without standards. Superintendent Crooker was determined to set those standards.

An early biography of Bethune characterized her as a specialist in public school buildings, and at her 1891 lecture at the Womenâs Educational and Industrial Union she was asked about being known as a school architect.3 Bethune responded that she did not want to be thought of as a specialist to the exclusion of other types of buildings and that as a âpioneerâ woman architect it was important for her to design the full range of building types.

In the 1880s, Bethuneâs early career did focus on schools. This was a specific moment in American cultural development; in industrial development and in urban development.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11812)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8969)

Paper Towns by Green John(5177)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5174)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5079)

Industrial Automation from Scratch: A hands-on guide to using sensors, actuators, PLCs, HMIs, and SCADA to automate industrial processes by Olushola Akande(5046)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4292)

Be in a Treehouse by Pete Nelson(4032)

Never by Ken Follett(3937)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3848)

Goodbye Paradise(3798)

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro(3390)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(3384)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3369)

The Cellar by Natasha Preston(3333)

The Genius of Japanese Carpentry by Azby Brown(3286)

120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade(3261)

Reminders of Him: A Novel by Colleen Hoover(3088)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3070)