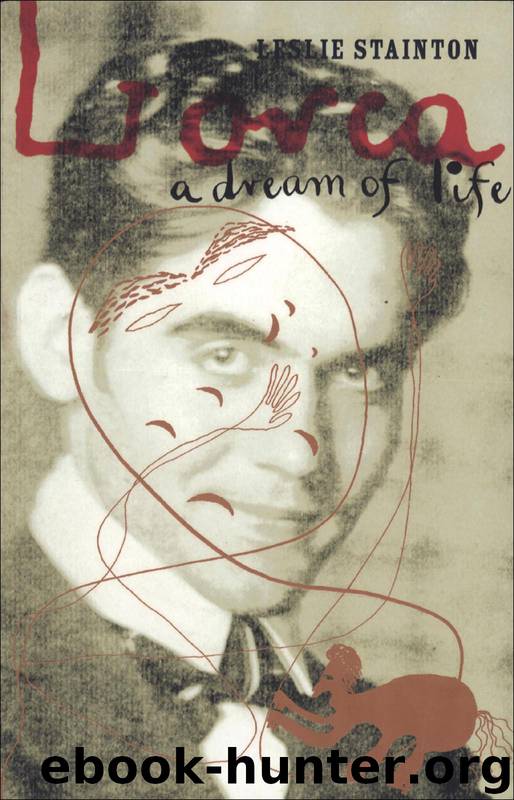

Lorca by Leslie Stainton

Author:Leslie Stainton

Language: eng

Format: mobi

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing

Published: 1998-09-03T21:00:00+00:00

Lorca had no sooner finished Blood Wedding than he set off on his second expedition with La Barraca. The group left Madrid on August 21 for a tour of northern Spain, including Galicia, where they received flattering press coverage. One reviewer hailed the company as an emblem of “freedom” and “revolution.”

The tour went smoothly. In cities and villages along the country’s verdant northern coast, audiences welcomed the young troupe. According to Lorca, La Barraca typically attracted two types of people: writers and intellectuals, and those Lorca simplistically described as “rustic campesinos,” poorly educated men and women who worked in fields and factories. The single group that did not warm to the company, he said, was the “frivolous and material-minded” bourgeoisie. Despite the fact that he and his family belonged to it, Lorca despised Spain’s middle class. He accused it of having “killed” the theater, of having “perverted it.” His remarks seemed not to affect his affluent parents, who over the years had grown accustomed to their son’s hyperbole.

In interviews and conversation Lorca insisted time and again that La Barraca’s best audiences were ordinary Spaniards. They “know what the theater is. They gave birth to it.” Although they might not grasp the intellectual or theological ramifications of a play such as Calderón’s Life Is a Dream, he noted with condescension, they could nevertheless “feel it.” Lorca loved to study the crowds who came to watch La Barraca, to scrutinize their response to the company’s work. He relished their slightest gesture of approval. The purity of people’s reactions to the troupe reaffirmed his faith in the power and magic of the theater. On the day after a performance, villagers would often spot Barraca actors on the street, and in their excitement cry out, “She was so and so! He was that one!” An elderly man once murmured wistfully to several company members, “How I’d love to travel around with you to God’s little villages, playing the fool.”

On reaching a new town, Lorca often struck out by himself to explore the sights while his crew unpacked costumes and set up the stage. Dressed in his blue mechanic’s coveralls, with the Barraca emblem boldly displayed on his breast pocket, he visited churches and monuments and chatted with townspeople. He often gave coins to the curious children who inevitably clustered around him. He loved playing the star. Occasionally he made a clumsy attempt at helping with preparations for the evening performance, but for the most part he left his colleagues to attend to the more mundane tasks of their enterprise. Despite his affection for the working-class uniform he wore with such pride, Lorca disdained manual labor and used his childhood limp as an excuse to avoid it. “Federico was not made for physical work,” one company member recalled kindly.

In most towns the routine was the same. The troupe arrived by truck and selected a performance site—often in a square backed by a picturesque church or civic building. As they unpacked, a town crier would roam the streets, announcing their presence.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Hating Game by Sally Thorne(19216)

The Universe of Us by Lang Leav(15057)

Sad Girls by Lang Leav(14397)

The Lover by Duras Marguerite(7887)

The Rosie Project by Graeme Simsion(6363)

Smoke & Mirrors by Michael Faudet(6175)

Big Little Lies by Liane Moriarty(5780)

The Shadow Of The Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafón(5680)

The Poppy War by R. F. Kuang(5674)

An Echo of Things to Come by James Islington(4842)

Memories by Lang Leav(4791)

What Alice Forgot by Liane Moriarty(4617)

From Sand and Ash by Amy Harmon(4488)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(4084)

The Tattooist of Auschwitz by Heather Morris(3834)

Ficciones by Jorge Luis Borges(3620)

Guild Hunters Novels 1-4 by Nalini Singh(3454)

The Rosie Effect by Graeme Simsion(3451)

THE ONE YOU CANNOT HAVE by Shenoy Preeti(3361)