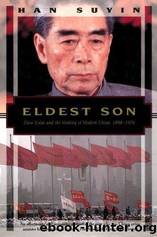

Eldest Son: Zhou Enlai and the Making of Modern China, 1898-1976 by Han Suyin & Suyin Han

Author:Han Suyin & Suyin Han [Suyin, Han & Han, Suyin]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Enlai, China -- History -- 20th century., Biography & Autobiography, Prime ministers -- China -- Biography., General, Zhou, 1898-1976.

ISBN: 9781568360843

Google: W0QAAAAACAAJ

Publisher: Kodansha International

Published: 1995-01-15T07:34:00.452208+00:00

and free discussion within and without the Party. It was called the Hundred Flowers Movement, from a classic snatch of poetry, "Let a hundred flowers bloom / A hundred schools of thought contend." Guo Moro, the poet, in a discussion with Mao on various philosophies which flourished in China around 500 B.C., had lit upon this phrase. "Chairman Mao," he told me, "approved of the title."

In April 1956, Mao delivered a long, rambling discourse to a meeting similar to the one Zhou had addressed in January. In May, Lu Dingyi, the Minister for Propaganda, circulated this speech, somewhat abridged and edited, in all the universities.

That April, I returned to China for the first time since 1949. The internal document, entitled "Let a Hundred Flowers Bloom, A Hundred Schools of Thought Contend," was handed to me by my cousin, a professor at the university. Guo Moro, with whom I had a long talk three weeks later, confirmed its importance. "What we want is an intellectual renaissance, which means freedom of debate." Fei Xiaotung, a social scientist, had proclaimed the document a "major thaw," a "reliberation of the intelligentsia." But other knowledge-bearers, dismayed by the purges, were skeptical. "Those who do not open their mouths are still able to think," another cousin of mine, a scientist, told me. "Those who talk are deprived of the right to think. I am not going to talk."

On June 25,1 met with Zhou Enlai and his wife, Deng Yingchao, at their private residence in Zhongnanhai. I had prepared many questions, under six headings. Three headings concerned the knowledge-bearers, freedom of speech, and political representation of other parties in the government.

I had seen Zhou Enlai in Chongqing in 1941 and fifteen years later he did not appear older. His eyes sparkled. He exuded cheerful confidence. I was to see him again about a dozen times and have long talks with him eleven times in the course of the next nineteen years. On only one other occasion did I see him as burst-ingly happy, almost glowing with joy, as in that June of 1956. And that second time was in 1972, after President Richard Nixon's visit to China.

The living room was starkly simple: a worn-out sofa covered in nondescript gray cloth, some chairs, with those lace antimacassars still favored in China. It could have been any minor university professor's living room. No antiques, no priceless porcelain, no paintings of value. Gung Peng, my friend, Zhou's press relations

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4296)

Never by Ken Follett(3937)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3848)

Unfinished: A Memoir by Priyanka Chopra Jonas(3383)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3370)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3073)

Will by Will Smith(2911)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(2352)

It Starts With Us (It Ends with Us #2) by Colleen Hoover(2345)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(2324)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(2300)

The Storyteller by Dave Grohl(2229)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(2219)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(2197)

The Becoming by Nora Roberts(2189)

The Stranger in the Lifeboat by Mitch Albom(2113)

Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr(2104)

Love on the Brain by Ali Hazelwood(2062)

Einstein: His Life and Universe by Walter Isaacson(2012)