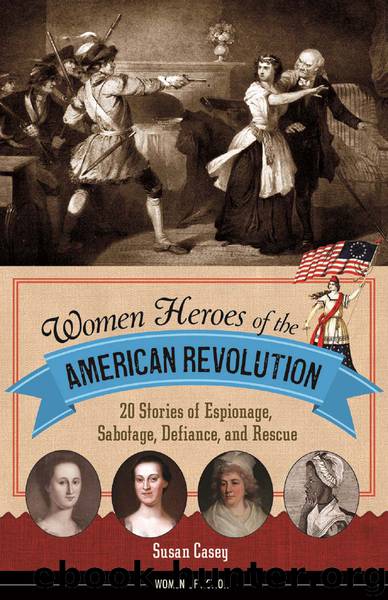

Women Heroes of the American Revolution by Susan Casey

Author:Susan Casey

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Chicago Review Press

Published: 2015-05-24T16:00:00+00:00

Mary Lindley was born in 1726 and raised in Pennsylvania, the daughter of Thomas Lindley, a blacksmith who had moved from Ireland to Pennsylvania in 1719. Thomas Lindley was a Quaker, a member of a religious group that believed in neutrality in time of war. With other Quakers, he started a company called Durham Furnace, a successful venture that Mary may have visited as a girl and seen its forges and furnaces and its production of iron stoves, tools, and pots.

Mary’s father was a man of influence, connected with men of power and sway in Pennsylvania. She witnessed him being appointed justice of the peace in 1738 and receiving an appointment to the Pennsylvania Assembly a year later.

Mary met Robert Murray, one of her family’s neighbors. He was an Irish-born merchant who was a descendant of a noble Scottish family. His roots were in England, but he sought his fortune in America and was successful, due in part to connections with influential merchants he met through Mary’s father. When he wanted to marry Mary, he abandoned his religion and became a Quaker. The two married in 1744, a year after Mary’s father died.

Years before the outbreak of the Revolution, Robert Murray was trading goods in places as far-flung as the West Indies, selling flour and wheat from the Pennsylvania mills. Later, the family moved to New York, where Robert’s business also thrived.

Both Robert and Mary were Quakers, understood to be neutral in times of war. Yet when tensions began increasing between the British and the colonists in the early 1770s, they had their leanings. Robert was thought to be a loyalist, sympathetic to the British cause due to his many British business connections. Members of Mary’s family served on both sides. While Mary was apparently loyal to her husband, she was also thought to be sympathetic to the struggle for independence.

How did Mary’s sympathy with the Whigs—supporters of the Revolution—play a part on that chaotic day of September 15, 1776? Or did it?

As Major General Israel Putnam was leading his 3,500 troops, a third of the Continental Army, out of town, he was cautious. He knew his troops would be no match for the well-trained British Army or their hired mercenary troops (the Hessians from Germany) who were heading into New York City to join the other victorious troops. Putnam didn’t want to get cornered by them, trapped on the southern end of Manhattan Island. Only the day before, a British officer had written of one patriot soldier who had encountered a Hessian soldier in New York: “I saw a Hessian sever a rebel’s head from his body and clap it on a pole in the entrenchments.”

To avoid meeting the British troops, Putnam led his troops northward along a road that edged the North (Hudson) River to a fork that would connect to another road on which he and his troops could safely march and then rejoin the rest of the Continental Army troops in Harlem Heights.

This turned out to be a bad plan.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4024)

Pocahontas by Joseph Bruchac(3734)

Unfiltered by Lily Collins(3616)

Cracking the GRE Premium Edition with 6 Practice Tests, 2015 (Graduate School Test Preparation) by Princeton Review(3605)

The Emotionary: A Dictionary of Words That Don't Exist for Feelings That Do by Eden Sher(2959)

Factfulness_Ten Reasons We're Wrong About the World_and Why Things Are Better Than You Think by Hans Rosling(2761)

The President Has Been Shot!": The Assassination of John F. Kennedy by Swanson James L(2740)

The Daily Stoic by Holiday Ryan & Hanselman Stephen(2718)

Rogue Trader by Leeson Nick(2482)

Sapiens and Homo Deus by Yuval Noah Harari(2426)

Gettysburg by Iain C. Martin(2332)

The Rape Of Nanking by Iris Chang(2332)

Almost Adulting by Arden Rose(2303)

500 Must-Know AP Microeconomics/Macroeconomics Questions(2247)

The Plant Paradox by Dr. Steven R. Gundry M.D(2054)

In the Woods by Tana French(2012)

Make by Mike Westerfield(1975)

The 48 laws of power by Robert Greene & Joost Elffers(1936)

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change (25th Anniversary Edition) by Covey Stephen R(1844)