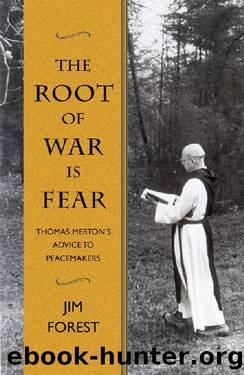

The Root of War is Fear: Thomas Merton's Advice to Peacemakers by Jim Forest

Author:Jim Forest [Forest, Jim]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Orbis Books

Published: 2016-08-17T22:00:00+00:00

Calligraphy by Thomas Merton (Thomas Merton Center, Bellarmine University)

Jesuit priest and poet Dan Berrigan, then on sabbatical in France, met us on arrival in Paris. A highlight of our three-day stay there was a meeting Dan had arranged with Jean Daniélou, fellow Jesuit priest and eminent scholar of the early church. Daniélou, later made a cardinal by Pope Paul VI, was one of the theological advisors—periti—for the Second Vatican Council. He spoke to us about theologians of the first centuries of the Christian era, such saints as Gregory of Nyssa and his brother Basil the Great, who, using the modern term, could be described as pacifists.

Jim Douglass, then doing doctoral work at the Gregorian University in Rome, became part of our group once we arrived at Leonardo da Vinci Airport. Among meetings Jim had arranged for us was one with curia member Augustin Bea, whom Pope John had made a cardinal in 1959 with the special task of heading the newly created Vatican Secretariat for the Promotion of Christian Unity. Bea, a German Jesuit and biblical scholar, was one of the bishops most closely linked with Pope John's aspirations for the Vatican Council. Welcoming our small group, he made clear how pleased he was to see Catholics and Protestants collaborating for peace. Responding to questions about the Vatican Council, he remarked on the divisions that existed among the bishops regarding the proposed condemnation of war fought with nuclear weapons and recognition of the right of refusal to condone or participate in war in any form—topics that were to be addressed in the council document on the church in the modern world, then known as Schema 13, still in the drafting stage. “There is resistance among some members of the American hierarchy to the Council taking a new direction in these matters,” said Bea. The several Catholics at the meeting laughed at his polite understatement. “Your efforts are needed,” Bea added, raising his hands and eyes toward heaven.

The following week we were in Prague. “Our stay here began bleakly,” I wrote afterward to Merton, “but little by little a more hidden city revealed itself. We arrived, tired from traveling, having had little sleep and no time to unpack more than toothbrushes. Even the sun seemed gray. The Soviet-style hotel, built by forced labor we were told by our hosts, was unpleasant. But each day, quietly and in small ways, we discovered how wrong first impressions can be. Self-effacing Prague is a city of hidden virtues.”

In his response Merton wrote: “I believe what you say about Prague. One of the most impressive Christians I have ever met is Jan Milic Lochman from the Comenius [theological faculty] there. He was here this spring. I got a card from him the other day. I feel I have much more in common with him than with many American Catholics.”2

At the time Czechoslovakia was experiencing the “Prague Spring”—“socialism with a human face,” was the widely used phrase. Our hosts proudly showed us a vacant pedestal on which a giant statue of Stalin once stood but lately had been removed.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(3258)

Victory over the Darkness by Neil T. Anderson(2386)

The Gnostic Gospels by Pagels Elaine(2026)

Devil, The by Almond Philip C(1899)

The Nativity by Geza Vermes(1849)

The Psychedelic Gospels: The Secret History of Hallucinogens in Christianity by Jerry B. Brown(1826)

Going Clear by Lawrence Wright(1571)

Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief by Lawrence Wright(1570)

Barking to the Choir by Gregory Boyle(1507)

A TIME TO KEEP SILENCE by Patrick Leigh Fermor(1499)

Old Testament History by John H. Sailhamer(1495)

Augustine: Conversions to Confessions by Robin Lane Fox(1473)

A History of the Franks by Gregory of Tours(1398)

The Knights Templar by Sean Martin(1393)

A Prophet with Honor by William C. Martin(1373)

The Bible Doesn't Say That by Dr. Joel M. Hoffman(1372)

by Christianity & Islam(1347)

The Amish by Steven M. Nolt(1253)

The Time Traveler's Guide to Medieval England by Ian Mortimer(1215)