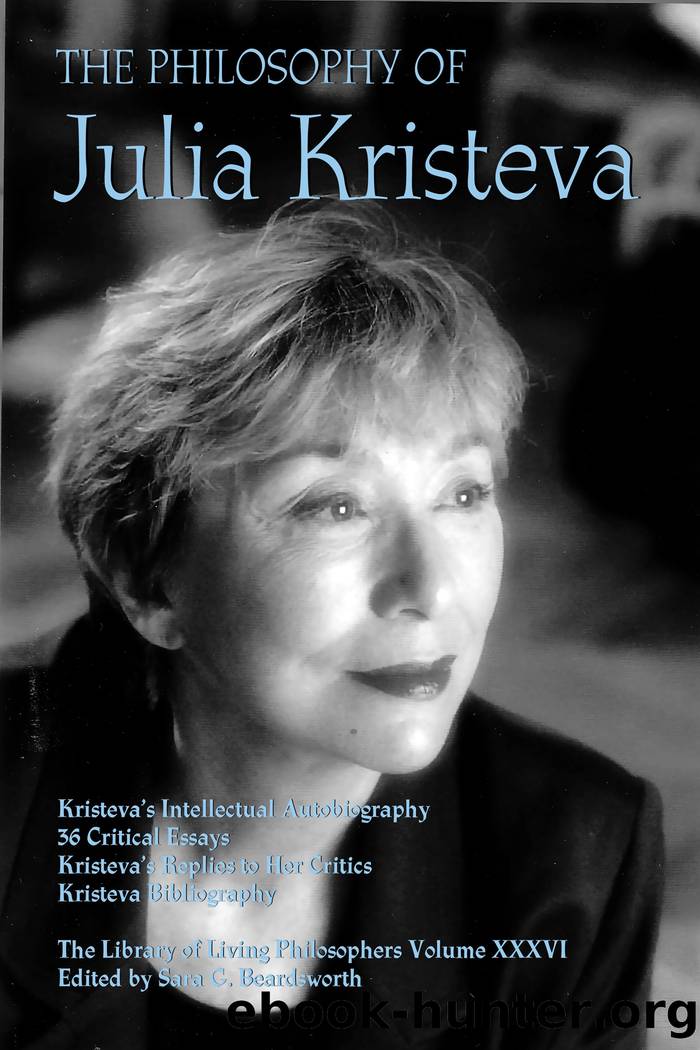

The Philosophy of Julia Kristeva by Sara G. Beardsworth;

Author:Sara G. Beardsworth; [Beardsworth;, Sara G.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780812694932

Publisher: LightningSource

Published: 2020-09-15T05:00:00+00:00

Translated from French by Armine Kotin Mortimer. An earlier version of this chapter appeared as âDu côté de chez Stéphanie Delacour,â in Julia Kristeva, Prix Holberg 2004, ed. Isabelle Rieusset-Lemarié (Paris: Fayard, 2004).

REPLY

TO DAVID UHRIG AND PIERRE-LOUIS FORT

It was a while before I dared to let myself be absorbed by a character or create a narrative.1 Was it my experience of psychoanalysisâwhich had already taken me from the couch to the armchair? Was it motherhoodâwhich nurtured and revitalized me in French, having become my mother tongue and the cradle of vocalizations and fantasies? Was it the impasses, if not the looming âendâ of history, the bankruptcy of providential ideologies, and the disappointment with the political that culminated with my trip to China? Philosophy and the human sciences lacked the luxurious appeasement that fiction and the imaginary bring to language. The novel seemed to me the propitious place to let this endless end be heard.

Bakhtin, whom I had introduced in France, had revealed, in symbolizing Dostoyevsky, that the novel is a polyphonic, mosaic, kaleidoscopic genre. I agreed wholeheartedly with this polyphony. Freud, attentive to the cumulative temporal diversities in the dreams and memories of his patients, had discovered the time-outside-time (Zeitlos) of the unconscious. What other composition, if not the polyphony of novels, would give resonance to psychosis, that brutal reality of globalized humans to which globalized criminality bears witness?

My novels are better liked in foreign countries, and yet French is now my only language for writing. My French was that of an immigrant. In it I would write the fortunes and misfortunes of the uprooted, and I have never learned to inhabit its phonemes and its syntax the way Colette and Proust were able to. Writing fiction also impressed itself upon me like an unconscious necessity that âfalls upon youâ: an infralinguistic experience, tied up with the melody of the sensible that runs under sentences and even more so with the tempo of the polyphonic narrative structure itself, set with philosophical and political insertions. Impossible to continue without all that. I decide nothing when I scribble notes in my âtravel notebookâ or when I write page after page in the middle of the night. One of my analysands, visibly in a phase of positive transference, told me he was convinced that I âlike to take down the mirrorâ when I write my novels. Itâs true, âIâ decompose âmyselfâ into multiple facets: images from childhood and family are present but disseminated within a historical fabric, a whirlwind of âestrangementsâ and âtransubstantiations.â2

During the night, between two dreams, waking up is a necessity for meâit is not insomnia but a paradoxical lucidity that nevertheless blinds me. Suspending my vigilance, letting myself submerge into that âdark spotâ Freud speaks of (sensation, fragrance, or brutality, sentence or idea) that occupies all space in the darkness.3 Flinging myself toward this âdark spotâ the way one who jumps from the sixth floor. Speed is my element, Time has become my main character: to write time for the times.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Power of Myth by Joseph Campbell & Bill Moyers(1070)

Half Moon Bay by Jonathan Kellerman & Jesse Kellerman(989)

A Social History of the Media by Peter Burke & Peter Burke(989)

Inseparable by Emma Donoghue(985)

The Nets of Modernism: Henry James, Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, and Sigmund Freud by Maud Ellmann(917)

The Spike by Mark Humphries;(814)

The Complete Correspondence 1928-1940 by Theodor W. Adorno & Walter Benjamin(790)

A Theory of Narrative Drawing by Simon Grennan(784)

Culture by Terry Eagleton(778)

Ideology by Eagleton Terry;(744)

Farnsworth's Classical English Rhetoric by Ward Farnsworth(722)

World Philology by(720)

Bodies from the Library 3 by Tony Medawar(713)

Game of Thrones and Philosophy by William Irwin(713)

High Albania by M. Edith Durham(708)

Adam Smith by Jonathan Conlin(701)

A Reader’s Companion to J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye by Peter Beidler(690)

Comic Genius: Portraits of Funny People by(657)

Monkey King by Wu Cheng'en(656)