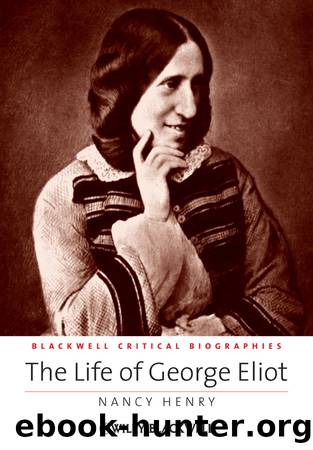

The Life of George Eliot by Nancy Henry

Author:Nancy Henry

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Wiley

Published: 2012-02-16T16:00:00+00:00

Sexuality in Romola

The question of where Eliot might have seen a mind like Tito's reflects the general wonder readers still feel at her psychological insights. Sometimes, however, readers have misread aspects of her fiction by not giving her enough credit for knowing. In his George Eliot (1902), Leslie Stephen criticizes the femininity of Tito and what he perceives as Eliot's failure to capture the true spirit of the time. He invokes The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini (written 1558–62, published 1728) as the epitome of a culture in which “the elementary human passions have been let loose” (132) and “there is the strangest mingling of high aspirations and brutal indulgence” (133). He does not name homosexuality as one of those passions or indulgences, but the reference to Cellini implies it, given the explicit references to homosexuality in the Autobiography, which Eliot and Lewes read on their first trip to Florence in May of 1860 (Haight, Biography 325). Stephen argues that Eliot fails to capture the Renaissance spirit because she is a middle-class English woman who cannot comprehend the nature of the society she is describing, “and though by dint of conscientious reading George Eliot knew a great deal about the ruffian geniuses of the Renaissance, she could not throw herself into any real sympathy with them” (135).20 It is certain, however, that by “dint of conscientious reading,” Eliot knew more about the passions of Renaissance Florentine men than Stephen was able to imagine.

Eliot knew that sodomy was one of the many unchristian practices of which Savonarola wanted to purge Florence. On December 12, 1492, the reforming monk exhorted the Florentine public to “pass laws against that accursed vice of sodomy, for which you know that Florence is infamous throughout the whole of Italy” (Savonarola 157–8). Eliot did not include Savonarola's direct condemnation of sodomy in the novel, but through indirection, innuendo, and allusion, she conveyed the prevalence of love and sex between men on a spectrum, from the idealized love of the teacher for his pupil, as present in the dialogues of Plato that were being revived by the neo-Platonists, to the sodomy that young unmarried men often practiced with younger, passive boys and for which men were frequently arrested.21 She kept true to the historical record of the time she studied so extensively to recreate, but did so without saying what she, as a Victorian novelist, could not say directly in her fiction. This highly sophisticated, learned historical coding also reveals just how complex the relationship between real life “originals” and her fictional characters had become in the work that was her greatest experiment in recreating a time and place so remote from her own experience and the experience of her readers.22

Romola is Eliot's only novel in which people who really lived (Savonarola, Piero di Cosimo, Machievalli) and who are reproduced with accuracy to the historical record, interact with pure inventions (Romola, Tito, Tessa), which as far as we know have no historical “originals.” In her other novels, real people, including living authors, are mentioned.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Melania and Me by Stephanie Winston Wolkoff(1060)

Orlando by Virginia Woolf; Mark Hussey(1052)

The Class of 83 by Hussain Zaidi(1011)

Live in Love by Lauren Akins & Mark Dagostino(981)

Dancing in the Mosque by Homeira Qaderi(972)

A History of My Brief Body by Billy-Ray Belcourt(911)

Virginia Woolf by Between The Acts(796)

Just as I Am by Cicely Tyson(767)

The Common Reader, Book 1 by Virginia Woolf(763)

Stranger Care by Sarah Sentilles(758)

Robespierre: A Revolutionary Life by Peter McPhee(756)

The Schoolgirl Strangler by Katherine Kovacic(745)

1914 by Luciano Canfora(738)

Ariel (english and spanish Text) by Sylvia Plath(733)

Unforgetting by Roberto Lovato(730)

Harriet Tubman: The Biography by University Press(719)

Paris Without Her: A Memoir by Gregory Curtis(719)

Broken Horses by Brandi Carlile(718)

Berlin Diary: The Journal of a Foreign Correspondent 1934-41 by William L. Shirer & Gordon A. Craig(715)