The Archaeology of Byzantine Anatolia by Niewohner Philipp;

Author:Niewohner, Philipp;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Oxford University Press USA - OSO

Published: 2017-03-15T00:00:00+00:00

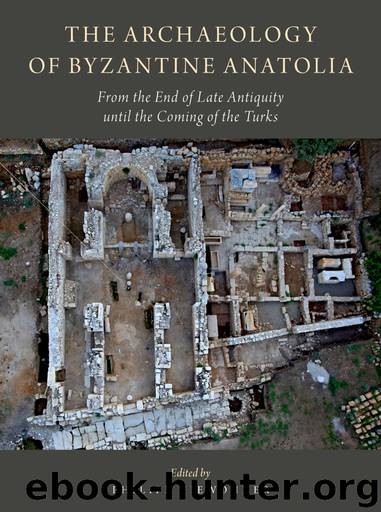

Fig. 19.3.

Ephesus, church in the so-called Serapeum (ÖAI/N. Gail)

The Byzantine history of the most famous ancient sanctuary of Ephesus, the Artemision, is little known.18 There are no indications of intentional Christian destruction or of an ongoing usage of the buildings. In particular, it can be ruled out that the temple was converted into a church. The sanctuary seems to have been left alone and gradually fell into ruin. This is well attested for an odeon inside the Artemision complex, the orchestra of which was filled with food waste during the sixth and the early seventh centuries. In the course of the Justinianic building program on the neighboring Ayasoluk Hill, which included the construction of the Basilica of St. John, an enclosure wall and a Byzantine aqueduct, both the standing remains and fallen parts of the Temple of Artemis, were thoroughly demolished, including the crepis and part of the foundations. Some of the marble appears to have been burned in lime kilns that were set up on the steps of the building; this suggests that the temple had intentionally been released for the quarrying of its stone material by the mid-sixth century at the latest. A second phase of robberies took place in the late Byzantine/Beylik period.

Early Byzantine Ephesus continued to be integrated into an international network of trade. Finds of amphorae that broke during loading and were deposited along the harbor canal include, in addition to a large-scale local production, imports from the nearby Aegean islands, the Black Sea region, Cilicia, Cyprus, the Levant, and Egypt, as well as Italy and Sicily. In contrast, Spanish imports are no longer found after the mid-fifth century. Particularly close trade connections existed with the African provinces, from which high-quality tableware—African Red Slip Ware—was imported in addition to agricultural products.19 This is also evident in many Carthaginian issues among the coin finds from Ephesus. The flow of imports continued throughout the sixth century and into the later seventh century before any caesura.

The rural hinterland of Ephesus and its agricultural production is attested by amphorae that were produced locally—LRA 3 and Ephesus 56—and contained above all wine;20 according to the find spots of those amphoras, Ephesian foodstuff was consumed throughout the Byzantine Empire and beyond, as finds from Britain and India attest. Small amphorae or ampullae from Ephesus that have been found in large quantities may have contained alum, which is mentioned as late as the fourteenth century as a regional commodity.21 In addition, the region around Ephesus was also known for textile production and the manufacture of high-quality cordage and rope. Furthermore, the trading of Anatolian marbles, which were shipped via the harbor of Ephesus, was of commercial significance. A water-operated stone saw provides evidence for the processing of the stone on site in the sixth century.22 Pollen analyses in the harbor basin indicate that the basin remained in frequent use into the seventh century, when it slowly transformed into a lagoon, which however remained connected to the open sea and accessible to ships.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Ancient & Classical | Greek |

| Medieval | Roman |

Letters From a Stoic by Seneca(2333)

The Valmiki Ramayana: Vol. 1 by Bibek Debroy(2175)

The Valmiki Ramayana: Vol. 2 by Bibek Debroy(2035)

The Valmiki Ramayana: Vol. 3 by Bibek Debroy(1858)

Mary Boleyn by Alison Weir(1461)

The Greeks by H. D. F. Kitto(1431)

The Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci by Da Vinci Leonardo(1250)

Art of Living by Sellars John;(1175)

Mythos (2019 Re-Issue) by Stephen Fry(1170)

The Voynich Manuscript by Gerry Kennedy(1163)

Annals by Tacitus(1158)

Medea and Other Plays by Euripides(1150)

The Classics by Mary Beard(1085)

Claudius the God by Robert Graves(1038)

Kadambari: Bana by Bana(1005)

Appeasement of Radhika by Muddupalani(1000)

Atlantis the Lost Continent Finally Found by Arysio Santos(998)

THE REPUBLIC by plato(992)

Beyond Control by Anthology(979)