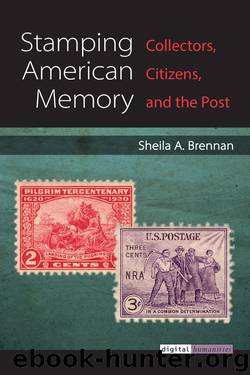

Stamping American Memory: Collectors, Citizens, and the Post by Sheila A. Brennan

Author:Sheila A. Brennan

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University of Michigan Press

Published: 2018-05-15T00:00:00+00:00

The stamp engraving reproduces the full-bodied statue of him that sits in Lafayette Park across from the White House in Washington. Kosciuszko appears larger than life as he looks down upon the stamp reader from his pedestal. Like many other Revolutionary War officers represented on stamps, he is standing, not on horseback, with sword drawn, and appears ready to lead a battle. Pulaski, who was a royal count, looks out from his portrait wearing a dress military uniform. Oddly, he is not on horseback, although he is credited as founding the American cavalry. No identifying language tells a stamp consumer that Pulaski died at the Battle of Savannah. And unless one read the newspaper announcements discussing the stamp, or as a collector purchased the first-day cover, the average American probably did not understand that the dates printed on the Kosciuszko, 1783–1933, celebrated his fictional naturalization.59

Obtaining these commemoratives was a great achievement for the fraternal and Polish heritage organizations that fought for these stamps to demonstrate ethnic pride and claim a piece of American heritage, and as another means for establishing their status as racially white. Even as cultural and legal definitions of whiteness were changing in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s, their members experienced discrimination and understood that Poles and other eastern Page 127 →European immigrants were defined as racially different from old stock immigrants hailing from western Europe. Celebrating Kosciuszko’s naturalization tells us that it was important for the Polish National Alliance, Polish Roman Catholic Union, and other organizations to broadcast their hereditary claims to Revolutionary lineage and American citizenship. The first naturalization law in 1790 dictated that only a “free white person” was eligible for citizenship. Kosciuszko qualified as white and fit for citizenship, contradicting the justifications behind immigration restrictions of people from Poland found in the Quota Act and Johnson-Reed. In the early twentieth century, Polish Americans were inching their way out of an in-between status, racially, and used the accomplishments of two Polish military men who volunteered (and died, in Pulaski’s case) for the American cause during Revolutionary War as their connection to the origins of the republic.60

Fig. 25. Kosciuszko, five cent, 1933 (Courtesy Smithsonian National Postal Museum Collection)

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life by Lilly Singh(7466)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5174)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4462)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4291)

Never by Ken Follett(3935)

Harry Potter 02 & The Chamber Of Secrets (Illustrated) by J.K. Rowling(3665)

The Heroin Diaries by Nikki Sixx(3543)

Urban Outlaw by Magnus Walker(3390)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3368)

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Book 3) by J. K. Rowling(3346)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3163)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3070)

The Club by A.L. Brooks(2919)

Will by Will Smith(2906)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2878)

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (7) by J.K. Rowling(2713)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2577)

The Chimp Paradox by Peters Dr Steve(2376)

Borders by unknow(2301)