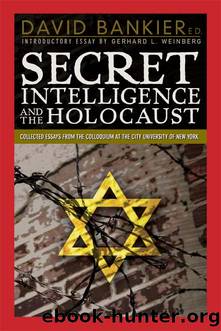

Secret Intelligence and the Holocaust by Gerhard L. Weinberg

Author:Gerhard L. Weinberg

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Enigma Books

As reporters of important and at times sensitive information, the nuncios and delegates were also constrained by the limitations of their communications channels. Like other diplomatic services, the papal service communicated primarily through the diplomatic pouch and telegrams. Papal diplomats had little confidence in the security of either method. Hard pressed to find the personnel and the money to support a courier system of its own, the Vatican usually entrusted its diplomatic mail to the couriers of other countries. Before the war it used the courier service of the Italian foreign ministry, but after Italy entered the war in June 1940 many parts of the world were closed to Italian couriers. The secretariat of state therefore accepted an offer from the Swiss foreign ministry to include papal mail in the bags carried by Swiss messengers. The secretariat may also have been influenced in its decision by evidence that Italian intelligence had been secretly opening the popeâs mail while it was in the custody of Italian couriers. Occasionally, the Vatican availed itself of the services of other countries. Papal mail to and from territories in the British Empire, for example, often traveled in the bags carried by the Kingâs Messengers. Under international law and convention, diplomatic bags were immune from search and seizure. In time of war, however, few intelligence services could resist the temptation to peek at the confidential communications of so important a neutral power as the Papacy. With some justification Vatican authorities simply assumed that papal diplomatic bags were vulnerable when in the custody of other governments. These authorities were no more confident about the security of their telegrams.

The Vatican was well aware that many foreign governments intercepted international telegraphic traffic for intelligence purposes and employed cryptanalysts to crack the ciphers that protected such traffic. Like other foreign ministries the secretariat of state encrypted its confidential communications, but its confidence in its ciphers was badly shaken in the first year of the war when it received credible information that both German and Italian intelligence had broken at least some of the Vaticanâs ciphers. The secretariat then concluded that no cipher (at least none contrived by the Vatican) could withstand the scrutiny of professional code breakers and that encrypted telegrams were not safe from prying eyes. âThey read everything,â a notation scribbled by a minutante in the margins of a report on Italian surveillance of Vatican communications, suggests the prevalent fatalism, as does the attitude of Monsignor Tardini who privately dismissed as âsimple-mindedâ the assurances from the British minister at the Vatican, Sir DâArcy Osborne, that his reports to London were fully secured by the Foreign Office cipher.11

During the war the Vatican discovered that communication of any sort, secure or otherwise, was difficult, if not impossible. Contact with its representatives abroad was often denied or delayed by the vagaries of war. Communications via letter and diplomatic pouch were especially problematic. The war devastated transportation networks in war zones and disordered those in neutral countries. Despite the strictures of international

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Archaeology | Essays |

| Historical Geography | Historical Maps |

| Historiography | Reference |

| Study & Teaching |

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(11266)

Navigation and Map Reading by K Andrew(4558)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(4553)

Barron's AP Biology by Goldberg M.S. Deborah T(3636)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(3517)

5 Steps to a 5 AP U.S. History, 2010-2011 Edition (5 Steps to a 5 on the Advanced Placement Examinations Series) by Armstrong Stephen(3407)

Three Women by Lisa Taddeo(2925)

The Comedians: Drunks, Thieves, Scoundrels, and the History of American Comedy by Nesteroff Kliph(2792)

Water by Ian Miller(2596)

Drugs Unlimited by Mike Power(2195)

DarkMarket by Misha Glenny(1849)

The House of Government by Slezkine Yuri(1848)

The Library Book by Susan Orlean(1738)

A Short History of Drunkenness by Forsyth Mark(1732)

Revived (Cat Patrick) by Cat Patrick(1681)

The Woman Who Smashed Codes by Jason Fagone(1651)

The House of Rothschild: Money's Prophets, 1798-1848 by Niall Ferguson(1620)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(1620)

Birth by Tina Cassidy(1573)