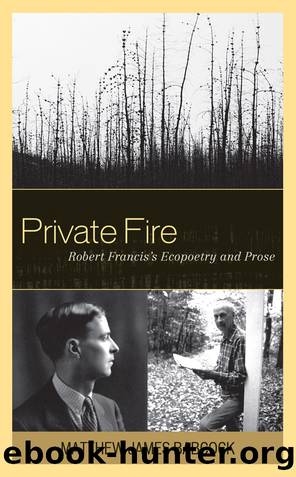

Private Fire by Babcock Matthew James;

Author:Babcock, Matthew James;

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 978-1-61149-023-7

Publisher: University of Delaware Press

THE STATE OF NATURE

âWar never won me over,â Francis opens chapter 4, âThe War,â in his autobiography. âThe waving of flags and the blowing of bugles never dazzled or seduced meâ (Trouble with Francis, 32). Francisâs staunch anti-war stance derived in part from his personal commitment to pacifism and his lifelong pilgrimage toward promoting concinnity between humanity and surrounding biospheric elements. Throughout his poetry and prose, Francis consistently pursues his belief that to flourish in oneâs natural settings one must also oppose the politically motivated destruction of wars waged against the earthâs human populations and against the progress and rejuvenation of the earthâs ecosystemic processes. Francisâs twin devotions to the preservation of life and landscape cast him as an American writer who saw no division between the political and the ecological, a position with which a generation of ecocritics would come to agree.5 Jonathan Bate, in The Song of the Earth, acknowledges this viewpoint. âThe dilemma of Green reading,â Bate argues, âis that it must, yet it cannot, separate ecopoetics from ecopoliticsâ (Bate, 266). As someone who lived through World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and Vietnam, Francis sidestepped the decades of international conflict and armed himself for combat with pencil and typewriter. Opposed to violence, he hummed the battle hymn of the hummingbird, joined the ranks of the soldier beetle, pledged his allegiance to peace, and aimed his most explosive poems at the wastefulness of twentieth-century warfare.

Writers and critics have often highlighted Francisâs gift for deftness and subtlety, but in his most volatile anti-war poetry, he exchanges deft subtlety for deafening subversion. âBruised by American foreign policy,â the speaker in âHogwashâ laments, âWhat shall I soothe me, what defend me with / But a handful of clean unmistakable wordsâ (7â9). The experimental post-Vietnam âPoppycockâ crows, âballyhoo from Madison A / ballyhoo from Washington DC / red-white-and-blue poppycock / Hurrah!â (21â24). The single-sentence satire âI Am Not Flatteredâ critiques those who tolerate wars from a distance: âI am not flattered that a bell / About the neck of a peaceful cow / Should be more damning to my ear / Than all the bombing planes of hell / Merely because the bell is near, / Merely because the bell is now, / The bombs too far away to hearâ (1â7). Perhaps autobiographical, âThe Articles of Warâ recounts an anonymous twentieth-century soldierâs simplistic desire to âresign from the Army,â a question which swells his barracks with derisive laughter (9, 13). âSomebody aghast at history,â the speaker finishes, âmay try / Resigning from the human race / . . . Haunted by the hawkâs eyes in the human face / Somebodyâcould it be I?â (16â20). âLight Casualtiesâ satirizes the sanitized politically correct phrase it takes for its title: âDid the guns whisper when they spoke / That day? Did death tiptoe his business?â (7â8). The fragmented and experimental âBlood Stainsâ lifts a home remedy for âhow to removeâ blood from household fabrics and applies it to the global need

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Universe of Us by Lang Leav(15076)

The Sun and Her Flowers by Rupi Kaur(14517)

Adultolescence by Gabbie Hanna(8927)

Whiskey Words & a Shovel II by r.h. Sin(8018)

Love Her Wild by Atticus(7758)

Smoke & Mirrors by Michael Faudet(6192)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5786)

The Princess Saves Herself in This One by Amanda Lovelace(4976)

Love & Misadventure by Lang Leav(4847)

Memories by Lang Leav(4800)

Milk and Honey by Rupi Kaur(4748)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(4556)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4348)

Pillow Thoughts by Courtney Peppernell(4284)

Good morning to Goodnight by Eleni Kaur(4234)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(4109)

Algedonic by r.h. Sin(4063)

HER II by Pierre Alex Jeanty(3611)

Stuff I've Been Feeling Lately by Alicia Cook(3458)