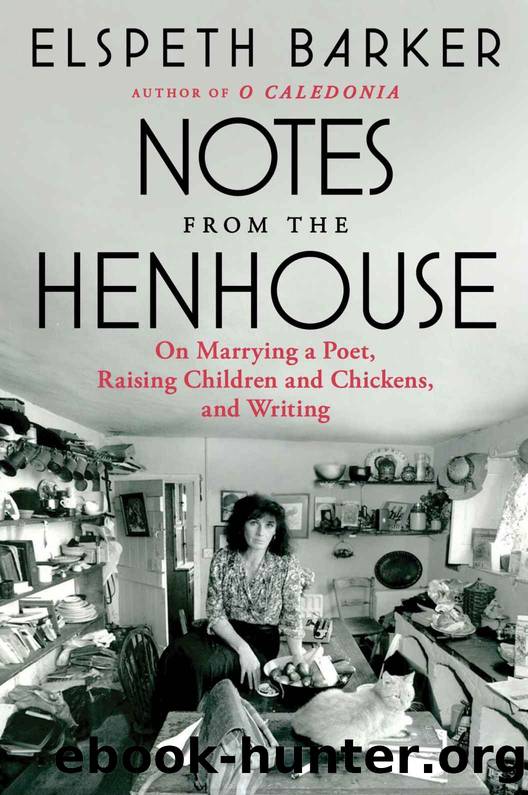

Notes from the Henhouse: On Marrying a Poet, Raising Children and Chickens, and Writing by Elspeth Barker

Author:Elspeth Barker [Barker, Elspeth]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Scribner

Published: 2024-03-19T04:00:00+00:00

FRIENDLY FIRE

âThere is a shift in the wind.â Oracular utterance, betokening woe. It was brought regularly by a kilted runner to my mother in her tower, from the far and dark recesses of the kitchen, the very shrine of the Aga, the household god, and its grim priestess, Cook. My mother would wring her hands and commence her customary smooth-running six-minute speech which treated with the injustice, inconstancy, and rigour of a life passed largely in an abnormal house, a vast stone castle crowned by battlements toppled regularly by this same wind, whose dominance extended even to the provision of lifeâs basic necessities. A shift in the wind meant that the Aga was dormant; it meant that dinner would be late, or that dinner would not happen. Good news, however, for us children, cosy by the nursery fire and looking forward to a supper of Heinz Tomato Soup (sometimes Celery) heated on Nannyâs Primus stove. Sometimes a jackdaw would provide diversion by crashing down the chimney into the fire, always to be saved, messily and energetically, by my brother. Otherwise this was a peaceful time, with the wind soughing and sighing through the pine trees far below and our motherâs militant voice fading into the downward maze which led to the kitchen.

Even better if the wind was wayward still in the morning. These days people speak highly of porridge, cooked slowly, all night long, in an Aga. Ha! Year in, year out, there it was on the breakfast table, a grey, lumpy quagmire, every spoonful to be eaten up, impossible to flick under the table to a helpful dog. Lucky the little ones at their Midlothian Oat Food in the nursery. I wondered often if the porridge was kept in a zinc-lined drawer in great rectangular slabs for daily reheating, as in Stevensonâs Kidnapped, but this I could never confirm, for children were not welcome in that kitchen. Nor was our mother, come to that.

It was a long, pale blue room, with a vaulted ceiling and a flagstone floor. A plain wooden table stretched from one end to the other, where the mighty triple-width Aga reigned from its raised dais. On the hot plates Aga kettles boiled continuously so that the air was hazed and steamy, and through the steam you might glimpse the white-clad forms of the irascible Cook and her acolytes, red of face, mighty of forearm. On the wall, usually askew, hung a Bateman print, âCook Doesnât Feel Like It,â depicting a drunken cook with her feet up on the table and an empty bottle rolling floorwards. But there were worse sights in the real and sober kitchen; bald, earless rabbits lay soaking in bowls of blood-tinged salted water, or brains or sweetbreads in gleaming coils. My motherâs terrier removed the sweetbreads once and carried them all the way upstairs and laid them by my bed so that my bare feet sank into them first thing in the morning. Other cheerless sights included the amputated dusty stumps of twenty-four geraniums, kept in their pots forever in the hope that one day they might live again.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Diaries & Journals | Essays |

| Letters | Speeches |

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(3915)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(3724)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(3701)

Pre-Suasion: A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade by Robert Cialdini(3422)

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara(3345)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3238)

What If This Were Enough? by Heather Havrilesky(2947)

The Day I Stopped Drinking Milk by Sudha Murty(2861)

Schaum's Quick Guide to Writing Great Short Stories by Margaret Lucke(2808)

The Daily Stoic by Holiday Ryan & Hanselman Stephen(2713)

Why I Write by George Orwell(2363)

Letters From a Stoic by Seneca(2337)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(2316)

A Short History of Nearly Everything by Bryson Bill(2138)

Feel Free by Zadie Smith(2104)

Insomniac City by Bill Hayes(2087)

A Burst of Light by Audre Lorde(1983)

Upstream by Mary Oliver(1940)

Miami by Joan Didion(1884)