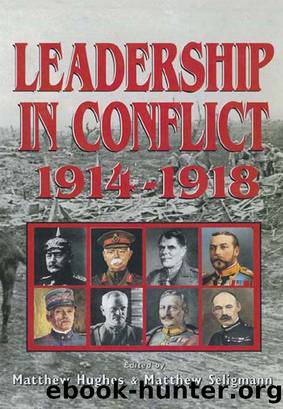

Leadership In Conflict 1914â1918 by Matthew Hughes Matthew Seligmann

Author:Matthew Hughes, Matthew Seligmann [Matthew Hughes, Matthew Seligmann]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781473815902

Barnesnoble:

Publisher: Pen & Sword Books Limited

Published: 1990-12-31T00:00:00+00:00

These instructions were put in a safe at Pershingâs headquarters in France and never revised.

What explains Pershingâs extraordinary powers, especially in a country that was profoundly unmilitaristic when the Great War began? Wilson loathed militarism, was suspicious of soldiers, and sought to limit their influence on society. His secretaries of navy and of war were decidedly anti-war if not pacifistic. The armed services were seen as instruments of national policy which only civilians determined. No generals or admirals, for example, had been consulted when Wilson made his decision for war with Germany.12 Yet he now made Pershing the virtual tsar of American participation.

Just prior to giving Pershing his instructions, Wilson had been informed of an alarmist assessment by Tasker H. Bliss, who served as acting Chief of General Staff when Scott was sent to Russia on the Root mission. Bliss argued âthat what both the English and French really wanted from us was not a large well-trained army but a large number of smaller units which they could feed promptly into their line as parts of their own organizations in order to maintain their manpower at full strength.â If the Americans fought only in battalions and regiments, there would be âno American army and no American commander,â and the US role in the war would be obscured.13 In these circumstances, Wilson feared he would have little influence at the peace table beyond economic and perhaps moral leverage. In his effort to repudiate power politics in world affairs, Wilson relied himself on the use of military force to achieve his political objectives. Pershingâs subsequent role in inter-Allied negotiations, on both military and political questions, abundantly demonstrated that Wilson could not have found a more effective instrument for the use of American arms to further his ânew diplomacyâ.

Wilsonâs tepid interest in most military questions and geography also played a part in Pershingâs virtual independence. The capitals of Paris and London were in close proximity to the battlefield and civil-military relations were characterized by distrust and acrimony as political and military leaders in frequent contact haggled over tactics, strategy, and other matters pertaining to the war. Separated from Washington by an ocean, Pershing talked with Wilson only once during the war, just before he departed for France.

Protective of American neutrality, Wilson had kept the general staff from developing contingency plans for US participation in the war.14 Military involvement in Europe after April 1917 was thus very much a work in progress. The forceful Pershing filled this void, and he did so without serious interference from the civilians, or for that matter, the Chief of the General Staff in Washington. He knew and almost always got what he wanted.

The American public was largely spared the heart-rending and bloody consequences of the killing fields on the Western Front. With the vast majority of US soldiers being withheld from combat until the last 110 days of the war, there seemed little to find fault with Pershingâs dominant role. Once US forces began to participate in major operations, however, the dead and wounded paralleled the losses suffered by the European armies.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life by Lilly Singh(7472)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5183)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4471)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4296)

Never by Ken Follett(3939)

Harry Potter 02 & The Chamber Of Secrets (Illustrated) by J.K. Rowling(3673)

The Heroin Diaries by Nikki Sixx(3544)

Urban Outlaw by Magnus Walker(3392)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3372)

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Book 3) by J. K. Rowling(3357)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3167)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(3073)

The Club by A.L. Brooks(2919)

Will by Will Smith(2912)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2880)

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (7) by J.K. Rowling(2714)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2578)

The Chimp Paradox by Peters Dr Steve(2383)

Borders by unknow(2304)